calsfoundation@cals.org

Orval Eugene Faubus (1910–1994)

Thirty-sixth Governor (1955–1967)

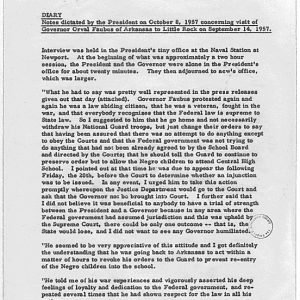

Orval Eugene Faubus served six consecutive terms as governor of Arkansas, holding the office longer than any other person. His record was in some ways progressive but included significant political corruption. He is most widely remembered for his attempt to block the desegregation of Central High School in 1957. His stand against what he called “forced integration” resulted in President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s sending federal troops to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to enforce the 1954 desegregation ruling of the Supreme Court.

Orval Faubus was born on January 7, 1910, in a rented log cabin on Greasy Creek in southern Madison County in the Ozark Mountains. His parents were John Samuel and Addie Joslin Faubus. Sam Faubus, a self-educated farmer, became a fervent opponent of capitalism. He named his three sons for socialist heroes; Orval’s middle name was Eugene for Eugene V. Debs.

In his youth, at his father’s urging, Faubus spent three months at Commonwealth College near Mena (Polk County), a left-wing, self-help institution. Pragmatism and ambition drove him toward the Democratic Party as Roosevelt’s New Deal took hold. In 1938, at the age of twenty-eight, tiring of the poverty of teaching in country schools in the winter and picking fruit in the summer, Faubus ran for and was elected circuit clerk and recorder of Madison County. He remained a politician for the rest of his life.

In 1931, he married Alta Haskins, a preacher’s daughter. She became a rural schoolteacher and, in later years, editor and publisher of the Madison County Record. They had one son.

Distinguished service in World War II gave Faubus’s political career a boost. He served as an Army intelligence officer in five major campaigns in Europe, including the Battle of the Bulge. He attained the rank of major.

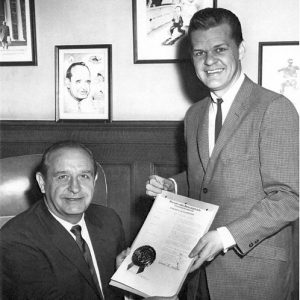

Faubus returned to the Madison County seat of Huntsville as postmaster. He and Alta bought the town’s weekly newspaper, the Madison County Record. Faubus’s editorials on education, healthcare, and highways caught the attention of Sidney S. McMath, himself a war hero and a leader of Arkansas’s GI Revolt, a campaign that swept away many old-line politicians. Faubus campaigned for McMath for governor in 1948 and was rewarded with an appointment to the state highway commission. That post, along with later service as an administrative assistant in the governor’s office, put him in touch with political activists all over Arkansas.

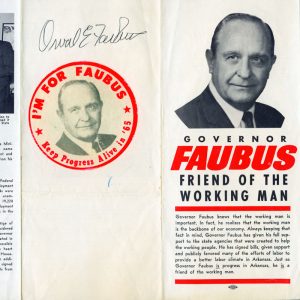

However, he was unknown among the general public. His challenge to Governor Francis A. Cherry, who had defeated McMath, was seen as an improbable undertaking in 1954. Nonetheless, he proved himself as a campaigner, attacking electric utility interests and Cherry’s political awkwardness. He stood up for old people on welfare, throwing Cherry’s unfortunate remarks about “welfare chiselers” and “deadheads” in his face. Faubus forced Cherry into a runoff in the Democratic primary.

Cherry panicked. When his advisors dug up Faubus’s old connection with Commonwealth College, he made it public in a way that suggested his opponent might be a communist. The tactic backfired; Faubus defeated Cherry by almost 7,000 votes. In the general election in November, he defeated Little Rock’s Republican mayor, Pratt Remmel, in a landslide.

Arkansas steadily industrialized during Faubus’s years as governor. Seizing on the new prosperity, he oversaw numerous improvements in public education, including a large increase in teachers’ pay. He initiated an overhaul of the embarrassingly bad State Hospital for the mentally ill; built the state’s first institution for underdeveloped children, the Arkansas Children’s Colony; expanded state parks; and forced the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to abandon plans to dam the Buffalo River. Hundreds of miles of highways were paved during his tenure. However, he also signed legislation creating the Arkansas State Sovereignty Commission in opposition to federal pressure to desegregate schools.

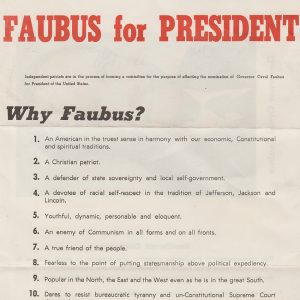

The defining moment of his political life was a constitutional crisis over school desegregation. The Little Rock School Board made cautious plans to place the first black pupils in all-white Central High School in September 1957, three years after the Supreme Court had ruled segregated schools unconstitutional. A federal district court endorsed the board’s plans. But growing resistance by segregationists caught the attention of Faubus. He was known as a racial moderate. He calculated, however, that a moderate would stand small chance of reelection in 1958 against a determined white supremacist.

On September 2, 1957, Faubus called out the National Guard to block the admission of nine black pupils to Central High School. His justification was that violence threatened and he had to preserve the peace. A federal judge ordered the guardsmen removed. The students, known as the Little Rock Nine, returned to the school but were met by a mob of enraged segregationists. The local police, unable to control the crowd, spirited the Nine out of the building. President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalized the National Guard and dispatched Army troops to restore order and enforce the court’s ruling. The troops stayed through the school year.

After Central High, Faubus and his allies, especially Attorney General Bruce Bennett, pursued legislation designed to bypass federal desegregation orders and limit the power of activists such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Act 10 of 1958 required state employees to list their political affiliations from the previous five years, while Act 115 of 1959 outlawed state employment of NAACP members. Act 4 of 1958 allowed the local school board to close any school threatened with desegregation, and so Little Rock voters closed its high schools for the 1958–1959 school year. Later, stung by bad publicity and facing economic decline, the city voted to reopen them with token integration.

Faubus continued his appeal to segregationists, as with his 1959 signing of HB 385, a law requiring blood donations to be labeled by race. A fire that same year at the Negro Boys Industrial School in Wrightsville (Pulaski County), during which twenty-one children were killed, solidified his national reputation. In addition, the scandal surrounding Arkansas Loan and Thrift, a hybrid bank that operated outside state banking laws, typified the corruption endemic during Faubus’s reign.

Faubus lost the battle with Eisenhower, but his actions ensured his election as governor four more times, despite the damage to the state’s image. He accumulated unprecedented power over Arkansas politics. His followers remained loyal even after the race conflict subsided. He was opposed by a substantial coalition of African Americans and white liberals and moderates, led by the Arkansas Gazette, from 1957 onward. He left office undefeated in 1967 after knocking off one opponent after another, including former governor Sid McMath, the millionaire Winthrop Rockefeller, and Congressman Dale Alford—all one-time allies who had turned against him.

Faubus habitually responded to his critics by sounding shocked and aggrieved. On the campaign trail in 1960, he demanded to know which accomplishments of “Faubusism” his opponents would end. Referring to one of his challengers, the Reverend H. E. Williams, Faubus would shout to the crowds, “Preacher Williams, do you want to close the Children’s Colony?”

Some observers have insisted that catering to the clamors of white supremacists was out of character for Faubus, a figure of pronounced country dignity and unusual public reserve. His personal convictions at the time were not virulently racist; indeed, his administration had favored the black minority in several instances. For example, he hired a number of black people in state government and saw to it that historically black colleges and other institutions received financial support. He joined a fight to abolish the discriminatory poll tax and replace it with a modern voter registration system. And the voters who repeatedly returned him to office seemed in part to be applauding their governor for standing up to an all-powerful federal government.

Faubus tried unsuccessfully three times—in 1970, 1974, and 1986—to recapture the governor’s office. However, a new generation of voters and leaders had moved into place.

Faubus’s personal fortunes declined after he left office. He briefly served as general manager of Dogpatch USA. His only child, Farrell, committed suicide in 1976. Orval and Alta divorced in 1969, and he and Elizabeth Westmoreland were married soon thereafter. Elizabeth was murdered in 1983 in Houston, Texas, where she was waiting to divorce Faubus.

Faubus spent his last years writing essays and memoirs and commenting on public affairs. He became increasingly conservative and often encouraged Republican office-seekers, although he insisted that he never voted for one. A Republican governor, Frank White, gave him his last political job, state director of veterans’ affairs.

Faubus and Jan Hines Wittenberg, a teacher, married in 1986. He lived with her in Conway (Faulkner County) until he died on December 14, 1994, of complications from prostate cancer. He is buried in Combs Cemetery on a hill above Greasy Creek in Madison County.

For additional information:

Faubus, Orval Eugene. Down from the Hills. Little Rock: Pioneer, 1980.

———. Down from the Hills, II. Little Rock: Pioneer, 1985.

Hemingway, Charles W. “A Burkeian Analysis of the 1954 Gubernatorial Campaign Speaking of Orval E. Faubus.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1971.

Orval Eugene Faubus Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://uark.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/1749 (accessed April 1, 2025).

Özdemír, Fatma Doğuş. “Red, White, and Black: Anti-Communism, Massive Resistance, and the Case of Orval Faubus.” MA Thesis, Bilkent University, 2008.

Pierce, Michael. “Orval Faubus and the Rise of Anti-Labor Populism in Northwestern Arkansas.” In The Right and Labor in America: Politics, Ideology, and Imagination, edited by Nelson Lichtenstein and Elizabeth Tandy Shermer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Reed, Roy. Faubus: The Life and Time of an American Prodigal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Terry, Bill. “The Hobo Who Became Governor: Orval E. Faubus Remembers.” Arkansas Times, October 1975, pp. 12–15, 27–28.

Roy Reed

Hogeye, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

My father has passed, but this was my father’s uncle. I remember my dad telling me stories about this uncle when I was a child.