calsfoundation@cals.org

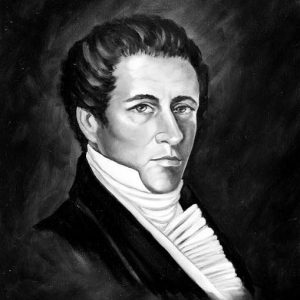

James Sevier Conway (1796–1855)

First Governor (1836–1840)

James Sevier Conway was the first governor for the state of Arkansas, elected in 1836 through strong family ties to both prominent Arkansans and President Andrew Jackson’s administration. His tenure as governor was best known for economic issues, surplus funds in the state treasury, legislation creating the state’s first banks, and a national depression, which consumed the surplus and contributed to a collapse in the banking system.

James Conway was born on December 4, 1796, in Greene County, Tennessee, the son of Thomas Conway and Anne Rector. Wealthy by frontier standards, the Conway family grew corn and cotton and raised livestock on their Tennessee plantation. Conway’s father employed private tutors to teach his seven sons and three daughters. In 1818, the family moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where Conway learned the art of land surveying from his uncle William Rector, surveyor general for Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Appointed as a federal land surveyor in 1820, Conway was assigned to survey the territory of Arkansas’s western boundary with the Choctaw Nation and the southern boundary with Louisiana. Conway surveyed the Choctaw boundary slightly to the south-southwest, rather than in a “true south” direction as instructed. This “improper” survey added over 100,000 acres to Arkansas and sparked a dispute with Choctaw leaders, which was not settled until 1886. In that year, the United States Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Choctaw claim but allowed Arkansas to keep the Conway survey. The Choctaw were compensated fifty cents per acre for the lost acreage.

In 1826, Conway married Mary Jane Bradley, daughter of a prominent pioneer family in the Red River area. The couple had ten children, five of whom died in infancy or early childhood.

In 1832, Conway was named surveyor general of Arkansas Territory. His income as a surveyor allowed him to purchase land along the Red River fifteen miles west of present-day Bradley (Lafayette County). By the mid-1830s, he owned more than 2,000 acres of land and eighty slaves. Now in the planter class, he built a larger house a short distance from his original dwelling and named his plantation Walnut Hill. His wealth also allowed him to build a summer cottage at Magnet Cove (Hot Spring County) and a bathhouse at Hot Springs (Garland County).

In 1828, his first foray into politics ended in defeat, but in 1831, he was elected to represent Lafayette and Union counties in the territorial legislature. Conway was part of an extended family that included the previously mentioned William Rector, Benjamin Johnson, a future chief justice of the state Supreme Court, and Ambrose Sevier, territorial delegate to the U.S. Congress and the state’s first United States senator. This Rector-Johnson-Conway-Sevier kinship came to be known as the “Dynasty” or “Family” because of their dominance of Arkansas politics and strong ties with the presidential administration of Andrew Jackson. Using those connections, Conway secured the Democrat Party’s nomination for governor at the party’s state convention, held in June 1836. He was not comfortable campaigning, however, and chose to state his positions on various issues by writing letters to key political leaders and Little Rock (Pulaski County) newspapers. Friends typically spoke on his behalf at the various political rallies held around the state. Even so, his family ties were enough, and in the general election held in August, he defeated Absalom Fowler, his Whig Party opponent, by a vote of 5,338 to 3,222.

Conway’s tenure as governor was a mixture of success and controversy. Under his administration, the state’s institutional structure took shape, including the banking system, the prison system, and an expanded network of public roads. With the Second Bank of the United States set to expire in 1836, Conway and other state leaders believed that it was crucial for the state to charter a bank that would furnish money and credit and serve as depository for surplus state funds. Two of the Arkansas General Assembly’s first actions were bills to establish a State Bank and a Real Estate Bank. These bills were also among the first for Conway to sign into law.

Becoming a state significantly reduced federal funds to build roads and maintain river channels for transportation, meaning added costs to the state if such services were to be maintained. Moreover, the state’s proximity to Indian Territory attracted a number of violent and lawless men, making it essential for the state to appropriate money to incarcerate those convicted of breaking the law. However, a rapid increase in the state’s population (from 52,240 to 97,574) during Conway’s four years in office greatly increased tax collections. That, coupled with turn-back funds from the federal government, allowed the young state to show a surplus in its treasury after only two years of operation. Conway asked the General Assembly to use the surplus funds to support a state university and a public school system. The assembly chose instead to reduce taxes.

The early success of the state’s finances caused problems for the Conway administration. The state constitution prohibited the legislature from levying taxes in excess of the revenue needed for normal operations. When the first year’s collection showed income exceeding costs, Conway called the General Assembly into special session to revise the tax code by reducing the rate of assessment. The state’s reduction in revenue, however, coincided with a national recession and a cutback in federal funds. The state’s banking system collapsed, and the state was plunged into economic turmoil. Conway did not benefit, financially, from the banks. However, their collapse caused the last two year s of his administration to be overshadowed by debt as the national “Panic of 1837” became a full-scale depression that continued for more than five years. The state went from a surplus of nearly $50,000 in the treasury to a deficit of over $65,000 in just two years.

Conway also found himself caught up in controversy. During the summer of 1836, reports circulated in Little Rock that Native Americans were gathering in force on the state’s western border and threatening to attack local settlements. To meet this threat, Conway assigned a militia unit of nearly 200 armed men to federal officials at Fort Towson. Strong disagreement arose among the troops over their choice for a commander. In an early election, the troops chose Absalom Fowler, a captain in the Pulaski County militia and Conway’s chief opponent in the gubernatorial election. When the troops rescinded their vote and chose Leban C. Howell from the Pope County unit, Conway supported Howell. Fowler refused to yield and ordered Howell arrested; Conway intervened. Fowler countered by demanding a court of inquiry to investigate the governor’s conduct. The court’s findings proved less than definitive, but Fowler boasted that his position had been vindicated. Conway released the court record to the newspapers along with a letter Fowler had written, which was highly critical of the governor. Public opinion supported Conway, and though Fowler dropped his charges, the incident greatly polarized political opinion.

Much of Conway’s tenure as governor was limited by his bad health. During the summer of 1838, he became seriously ill and considered resigning from office. He spent several weeks at Hot Springs and at home at Walnut Hill. Because of his health, he refused to seek a second term. He returned to his life as a planter. The remainder of his life was devoted to farming and local affairs. Long an advocate of education, he helped establish Lafayette Academy in his home county in 1842.

Conway died of pneumonia on March 3, 1855, and was buried in the family cemetery at Walnut Hill.

For additional information:

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Ross, Margaret. The Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years 1819–1866. Little Rock: Arkansas Gazette Foundation, 1969.

White, Lonnie. Politics on the Southwestern Frontier: Arkansas Territory, 1819–1838. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1964.

C. Fred Williams

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.