calsfoundation@cals.org

Grist Mills

Grist mills were an important economic driver for Arkansas from early settlement until the early to mid-twentieth century. Designed to grind corn into meal or process wheat into flour, the mills often served as a gathering spot within their respective communities. Even in areas of the state dominated by large-scale cash crops, grist mills served an important purpose as they transformed raw crops into usable foodstuffs.

Mills date back thousands of years, with references appearing in Greek and Roman sources. Although animals could be harnessed to help turn the millstone, in order to provide the constant motion needed to grind grain more effectively, water and wind were frequently utilized as a power source. Multiple examples of medieval water-powered mills exist in Europe, and this type of mill would become prevalent in the United States, including in Arkansas.

Early mills began operation in Arkansas before the territory became a state. Early settlers used hand mills to grind corn. These hand-powered mills were easy to transport and could be quickly set up, unlike grist mills, which require a more substantial power source. Thomas Nuttall recorded that at the time of his visit to Cadron (Faulkner County) in 1819, the residents were using hand mills, and he doubted that any grist mill had yet been constructed in the territory. This was not true, as Captain William Thompson had built a mill in 1817 near the future location of Evening Shade (Sharp County). He used the water of Mill Creek to power the wheel, and the success of the mill helped drive settlement in the area.

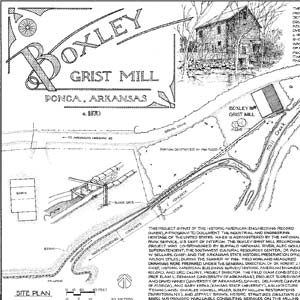

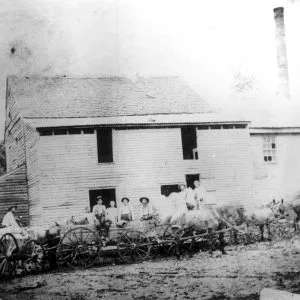

Grist mills in Arkansas were typically located near rivers, creeks, and other streams to provide for a constant source of power. Dams were often constructed to help manage the flow of water, and the remnants of some of these structures can still be found. As local farmers brought their harvested crops to be ground, mills became popular gathering places. The efficiency of using a grist mill when compared to a hand mill made the fee charged by the miller worth the cost. Millers typically retained part of the milled crop as their payment, often keeping one-eighth of the grain. The establishment of a mill often sparked settlement of an area, encouraging people to move nearby.

Grist mills proved to be an important military target during the Civil War, with both Union and Confederate forces targeting the structures in an effort to deny the enemy access to foodstuffs.

Multiple mills could operate at the same location, with one site in Drew County containing a grist mill, flour mill, sawmill, cotton gin, and sorghum mill. The use of mills declined in the early and mid-twentieth century as the number of rural residents in the state decreased and fewer farmers needed to grind grain.

Historic examples include Spring Mill, located in Independence County. With a dam constructed in 1867 and a mill building constructed in 1869, the mill operated for decades. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Villines Mill, located in Newton County within the boundaries of the Buffalo National River, dates to approximately 1840 and was reconstructed in 1870, operating for more than a century. It was added to the National Register in 1974.

While grist mills existed throughout the state, the fast-moving water found at higher elevations helped turn the massive water wheels needed to operate more efficiently. The wider, slower rivers located in the southern and eastern portions of the state often made it difficult for mills to operate, although some did successfully utilize waterpower. Osage Mills Dam, located Benton County, was constructed in 1890 to provide waterpower to a nearby mill; the site was added to the National Register in 1988. Pyeatte Mill, located at Cane Hill (Washington County), began operating in the 1830s. It moved in 1902 to the current site and not only made cornmeal and flour but also operated as a lumber mill. It operated until the 1920s, and its remains are now owned by the Cane Hill Restoration Association.

One of the most famous mills in Arkansas is not an actual grist mill, but rather a representation of an abandoned former grinding facility. The Old Mill in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) contains millstones and a former working iron grist mill, but the structure was never planned to be a functional mill. It is best known for appearing in the 1939 film Gone with the Wind.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Listings in the National Register.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45 (Winter 1986): 342–345.

Brandon, Jamie C. “Van Winkle’s Mill: Recovering Lost Industrial and African-American Heritages in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Winter 2008): 429–445.

Brandon, Jamie C., and James M. Davidson. “The Landscape of Van Winkle’s Mill: Identity, Myth, and Modernity in the Ozark Upland South.” Historical Archaeology 39, no. 3 (2005): 113–131.

Curry, Corliss C. “Early Timber Operations in Southeast Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19 (Summer 1960): 111–118.

Holcombe, E. A. “Spring Mill.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Summer 1961): 182–186.

“Osage Mills Dam.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/docs/default-source/national-registry/be2993-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=ba44b29d_0 (accessed June 10, 2025).

Hughes, Michael A. “Wartime Gristmill Destruction in Northwest Arkansas and Military-Farm Colonies.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 167–186.

Pitcaithley, Dwight. “Settlement of the Arkansas Ozarks: The Buffalo River Valley.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Autumn 1978): 203–222.

“Pyeatte Mill.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/docs/default-source/national-registry/wa0370-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=e451ec10_0 (accessed June 10, 2025).

“Spring Mill.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/docs/default-source/national-registry/in0498-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=cf5b332f_0 (accessed June 10, 2025).

Vaulx, Julia R. “Another Early Traveler in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 5 (Summer 1946): 169–178.

David Sesser

Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.