calsfoundation@cals.org

Winslow (Washington County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35°48’03″N 094°08’06″W |

| Elevation: | 1,756 feet |

| Area: | 1.82 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 365 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | February 27, 1905 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

289 |

264 |

363 |

248 |

248 |

183 |

227 |

247 |

342 |

399 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

391 |

365 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

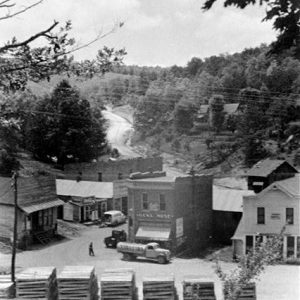

Winslow (Washington County) was reported to be the highest railroad pass on the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway line between the Rocky and Appalachian mountains. The elevation helped make Winslow a popular summer resort area for decades.

Pre-European Exploration though Louisiana Purchase

Southern Washington County has been inhabited for roughly 12,000 years. In the 1700s, the Osage claimed the land from the Arkansas River north into what is now central Missouri. Their main villages were in Missouri, but they traveled to north Arkansas to hunt. In the early 1800s, settlers began to move north from the river and south from Missouri Territory into the mountains of what is now northwestern Arkansas.

Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The stage lines became an important means of transit for people and mail. Elijah J. Woolum established the Woolum-Brown Stage Line operating between Fayetteville (Washington County) and Alma (Crawford County) sometime after the Civil War (the exact date is unknown). The stage stop became known as Summit Home. On December 11, 1876, an application was granted for a post office at Summit Home. William John Reed was the first postmaster. It is speculated that this stage line was part of the Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company route, but it has never been proven.

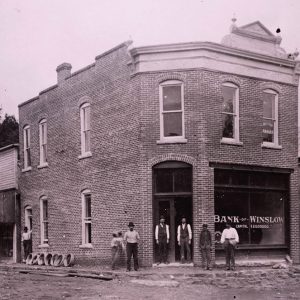

With construction of the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway in the early 1880s, the town flourished. As the railroad moved from Fayetteville through the West Fork (Washington County) valley, people moved south with it. The completion of the Winslow Tunnel in 1882 opened new economic opportunities to the town. Winslow-area residents harvested timber on a large scale for railroad ties and fence posts. On Saturdays, wagons lined up for miles in every direction to bring in the work of the week.

An application to the U.S. Post Office Department on August 3, 1881, changed the town’s post office name to Winslow. It was named for Edward F. Winslow, then-president of the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway.

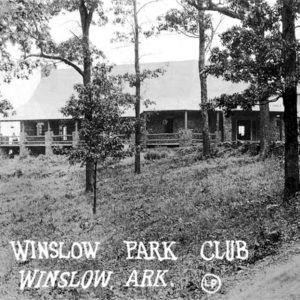

In the 1880s, Fort Smith (Sebastian County) physician Albert Dunlap visited the town. In 1887, he built a home, Boston Heights, and moved his family to Winslow. He encouraged his friends from Fort Smith to visit, thus beginning Winslow’s “resort era.” In the early 1900s, Thomas B. Harris, whose family originally came from Illinois as summer visitors, developed Winslow Park Club on a mountain east of town. It had a main lodge and thirty-nine individual cottages owned by “the summer people”—families who spent summers in Winslow. Many came from Fort Smith, others from cities in states as far away as Texas, Kansas, and Illinois.

Early Twentieth Century through World War II

On October 3, 1904, the citizens filed a petition to incorporate the city of Winslow. A charter was granted on February 17, 1905.

In 1908, Gilbert and Maud Duncan bought the Winslow Mirror newspaper from Louis B. Fitzgerald and renamed it the Winslow American. Distribution continued weekly until 1953.

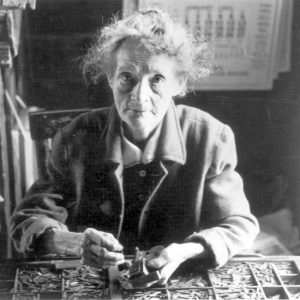

Maud Duncan, niece of Albert Dunlap, was one of the state’s few female pharmacists at this time. In 1925, she ran for mayor with an all-female city council and won. The “Petticoat Government” was elected for a second term in 1926, but the women declined to run for a third term.

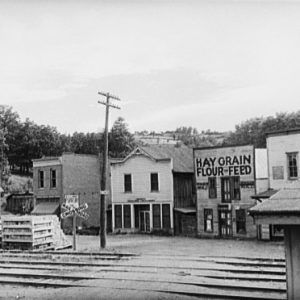

In the 1930s, drought affected the economy more than the Depression. The marketable timber was disappearing and major crops of apples, strawberries, and vegetables failed. As people moved west and automobiles became a primary source of transit, fewer people visited Winslow for the summer. Over the next three decades, hotels closed, buildings were razed, other buildings burned, and the town became a shell of its former self. During World War II, many of the young men went off to war. The women of the community took over the jobs of postmaster and depot agent and ran the businesses. After the war was over, Winslow had no industry to offer the returning soldiers. Families moving to cities and states where there was more economic opportunity caused a general decline in population. The residents who remained were either retired or working in nearby larger cities. As the children grew up, they also moved to areas with more opportunity.

Modern Era

In the late 1960s, the Winslow area attracted an influx of people looking to find a simpler life by growing their own food and raising their children away from the complications of the big cities. This is still true in the twenty-first century. The population continues to generally rise because many have found that the cost of living in a small town or in the country is less than in a more urban area. The majority of people work in Fayetteville, Springdale (Washington County), Rogers (Benton County), and Fort Smith. The completion of what is now Interstate 49 had mixed benefits—even though it bypassed the city of Winslow seven miles to the west, it has an on-ramp located there. Travel time to nearby cities has decreased, and residents living along Highway 71, the old main road, find living and traveling along the highway to be safer.

Education

In 1904, the Dunlaps donated Boston Heights to St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church to be used as the Helen Dunlap Memorial School, honoring their late granddaughter. The school originally accepted both boys and girls. After the first year or two, the name was changed to the Helen Dunlap Memorial School for Mountain Girls, and it became a boarding school for girls from many areas. The school was closed during the Depression years due to lack of funds, and the building was razed.

Winslow’s first public school building was a wooden structure built in 1894. The building burned in November 1918, and a brick schoolhouse was constructed north of it. That building burned in 1929, and the current stone building was built in 1930. After more than 100 years, Winslow School District was merged with Greenland School District in July 2004. The elementary school continues with classes on the Winslow campus, but the high school was closed at the end of the 2005 school year. The students now attend school in Greenland (Washington County) or other nearby high schools. The closing of Winslow High School was a major blow to Winslow’s economy; the school was the major employer of the area, employing more than fifty people.

Notable Figures

Douglas Clyde Jones, a career military officer turned award-winning novelist, was born in Winslow. He wrote more than a dozen books. Don West was a farmer, educator, and writer who published a memoir, Broadside to the Sun, about his family’s subsistence farming experience. His wife, Muriel West, was a noted poet and fiction writer, and their son, Timothy, became a reclusive artist living in the Winslow area.

Attractions

Ozark Folkways is an organization that strives to preserve the past by teaching and exhibiting crafts native to the region. They have retail space, workshop space, a free museum, and a resource library. Our Lady of the Ozarks Shrine, located just south of Winslow, was decreed a national pilgrimage site, and hosts two pilgrimages each year.

For additional information:

Brotherton, Velda. Images of America: Washington County, Arkansas. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1999.

Coley, Cheri, and Barbara Lewis. “The Village of Winslow in the 1880s: Helen Dunlap Memorial School.” Flashback 66 (Spring 2016): 3–15.

Winn, Robert G. Civil War in the Ozarks, Personal Glimpses. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1985.

———. Winslow: Top of the Ozarks. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1983.

Jo Ann Kyle

Winslow, Arkansas

Anderson's Cafe

Anderson's Cafe  Burns Gables: ca. 1953

Burns Gables: ca. 1953  Cole-Land Mercantile Company

Cole-Land Mercantile Company  Maud Duncan

Maud Duncan  Maud Duncan Museum

Maud Duncan Museum  Maud Duncan Display

Maud Duncan Display  Muxen Building

Muxen Building  Wally's Cafe

Wally's Cafe  Washington County Map

Washington County Map  Winslow Bank

Winslow Bank  Winslow City Museum

Winslow City Museum  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Winslow Church

Winslow Church  Winslow Park Club

Winslow Park Club  Winslow School

Winslow School  Winslow Shrine

Winslow Shrine  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Winslow View

Winslow View

I went through eighth grade in Winslow in 1965. I stayed at Boys Town of Arkansas, on the Hill.

I have searched all over and can’t find any articles about Boys Town and its director, Daddy Jack Gaysinger, who went on to be parole board commissioner.