calsfoundation@cals.org

Randolph County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Pocahontas |

| Established: | October 29, 1835 |

| Parent County: | Lawrence |

| Population: | 18,571 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 651.91 square miles (2020 Census) |

|

Historical population as per the U.S. Census: |

|||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

2,196 |

3,275 |

6,261 |

7,466 |

11,724 |

14,485 |

17,156 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

18,987 |

17,713 |

16,871 |

18,319 |

15,982 |

12,520 |

12,645 |

16,834 |

16,558 |

18,195 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17,969 |

18,571 |

|

|||||||

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

16,684 |

89.8% |

| African American |

140 |

0.8% |

| American Indian |

87 |

0.5% |

| Asian |

75 |

0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

596 |

3.2% |

| Some Other Race |

139 |

0.7% |

| Two or More Races |

850 |

4.6% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

384 |

2.1% |

| Population Density |

28.5 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$37,218 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$23,248 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

18.8% |

|

Randolph County’s five rivers, proximity to land transportation routes, and rich agricultural promise drew settlers to the area before the Louisiana Purchase. As dependence on water-based transportation fell, land and railroad routes allowed agriculture and industry to maintain the county’s economic prominence in northeastern Arkansas. The county is home to the Rice-Upshaw House, the oldest standing structure in the state, and Davidsonville Historic State Park, devoted to one of Arkansas’s earliest settlements. The county has six incorporated communities: Biggers, Maynard, O’Kean, Pocahontas, Ravenden Springs, and Reyno.

Pre-European Exploration

Hundred of archaeological sites exist in Randolph County, some dating back to 11,000 BC or perhaps earlier. As time progressed from the Dalton Period through the Archaic,the number of sites and the duration of occupation increased. Randolph County is filled with Archaic and Woodland period sites. Mississippian Period (AD 900–1600) is especially well-represented, with the remains of houses,underground storage pits, graves, and other features providing research opportunities for many teams of archaeologists.

European Exploration and Settlement

The first Europeans in Arkansas were Hernando de Soto and the members of his expedition in 1541–1542, but they did not travel as far north as Randolph County. France was the first European nation to claim the area, after Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet first explored the Mississippian River Valley in 1673 and then René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, claimed the land in 1682. The Spanish acquired the land in the Treaty of Paris of 1763 before transferring it back to the French in 1800.

A settlement of Michigamea—an Algonquian-speaking people from the Illinois Confederation—is said to have existed in the seventeenth century near modern-day Pocahontas. Small settlements of Shawnee, Delaware, and Cherokee groups briefly existed in northeastern Arkansas in the early nineteenth century, but they had left by 1820, probably due to the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812. Osage hunted in the area but established no permanent settlements.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Part of the Louisiana Purchase, the area became part of the District of Louisiana in 1804 before becoming the Louisiana Territory in 1805. The new territory subdivided, with the District of New Madrid containing the region. It became part of the District of Arkansas the next year. In 1812, the name of the governing territory changed to Missouri Territory, and the District of Arkansas converted to New Madrid County. In 1813, it became Arkansas County, with the upper part of the county separating as Lawrence County in 1815.

Before the Louisiana Purchase, a few Frenchmen had settled the region. American settlers quickly followed, entering through Hix’s Ferry. Established by William Hix around 1803, it became the major entry point to northeastern Arkansas on the Southwest Trail (also known as Old Military Road, Congress Road, or the Natchitoches Trace). In 1815, Davidsonville, near three rivers and the Southwest Trail, became the Lawrence County seat. This settlement produced Arkansas’s first post office in 1817, a land office in 1820, and a brick courthouse in 1822, as well as a cotton gin, a jewelry store, and a drill site for the Third Regiment of Territorial Militia. In the late 1820s, the town of Davidsonville waned as the Southwest Trail shifted westward, and the county seat changed to Jackson.

Coinciding with the founding of Davidsonville, Ransom Bettis established the Bettis Bluff settlement on the Black River. In the late 1820s, Thomas Stephenson Drew, future governor, arrived and began shipping pork and stock down the river, reinvesting the profits in trade items and gaining sizable landholdings by marrying Bettis’s daughter, Cinderella. Once the first steamboat arrived at Bettis Bluff in 1829, the town economically coalesced. In 1835, Randolph County separated from Lawrence, and Bettis Bluff, renamed Pocahontas, became the Randolph County seat. By 1839, a new county courthouse opened.

The five rivers located within the borders of the county are the Black, Current, Eleven Point, Fourche, and Spring. The rivers proved to be important in the economic development of the county, allowing for the shipment of goods to market.

William Looney and his family, along with a number of enslaved people, settled in the Eleven Point River valley. Looney operated numerous businesses including distilling brandy. His tavern still stands and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Cherokee removed from their eastern lands under the Andrew Jackson administration and guided by John Benge crossed the Current River into Randolph County in 1838 and moved through Jackson toward Smithville (Lawrence County). The economic benefits of the land route and the rivers continued to draw people to the region, increasing the population to more than 6,000 by 1860.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Of the more than 6,000 residents in the county in 1860, 5,902 were white with 359 people held in bondage. While the institution of slavery was not as important to the economy of the county as in other areas of the state, it did have an impact on the economic growth of the Randolph County.

The importance of Pitman’s Ferry, the old Hix’s Ferry site purchased by the Peyton R. Pitman family, made Randolph County an early Civil War assembly area, drawing soldiers into the region to outnumber the civilian population of the county at the time. Confederate general William Joseph Hardee took command at Pitman’s Ferry, transferring the state volunteers to Confederate service before shifting them east of the Mississippi River in the fall of 1861. The avenues of entry remained weakly defended, and small skirmishes and guerrilla activity ensued.

The largest engagement in Randolph County was fought on October 27, 1862, at Pitman’s Ferry. Colonel William Dewey of the Twenty-third Iowa Infantry marched thirteen companies and an artillery section to the ferry by force. Opposed by Confederate colonel John Q. Burbridge’s estimated 1,500 men, the Union forces carried the position. The number of engaged forces is estimated at more than 2,500. After the surprise and capture of Confederate General M. Jeff Thompson and his staff at Pocahontas in 1863, only skirmishes and guerrilla activity occurred as the county remained deep in Union territory. These skirmishes include actions at Buckskull and Cherokee Bay, and multiple expeditions into the county including in January 1864 and November 1864.

After the war, the construction of railroad routes near the county brought travelers and trade. The Hoxie-Pocahontas and Northern Railway Company, part of the St. Louis-San Francisco system, entered the county, expanding markets, encouraging land sales, and bolstering the lumber industry.

Post-Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

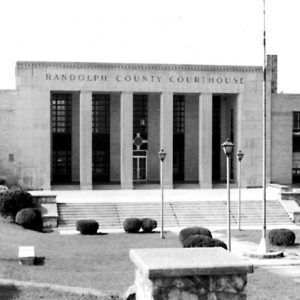

Postwar prosperity funded construction of a new courthouse in 1875, and easier travel encouraged the development of two nineteenth-century resort communities, Warm Springs and Ravenden Springs, around natural mineral springs. The improved transportation allowed for more immigration into the county. A large number of German families began migrating into Randolph County, creating a strong German Catholic presence in Pocahontas and Engelberg by the turn of the century. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the construction of U.S. Highways 62 and 67 coupled with Works Progress Administration (WPA) road construction and Civilian Conservation Corps projects helped Randolph County withstand the Great Depression. Pocahontas added a library, a waterworks, and a hospital before the construction of the current county courthouse in 1940.

Two lynchings took place in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both of white men suspected of committing crimes. George Cole was killed in 1872 after reportedly abusing his wife among other offenses. Accused of murdering a city marshal in 1901, George Shivery was hanged by a mob. The Barker-Karpis Gang committed its first murder in Pocahontas in 1931 when night marshal Manley Jackson died at the hands of the group.

World War II through Modern Era

The entrance of the United States into World War II had mixed results for Randolph County. The economic prosperity brought by war industry drew some citizens to better-paying jobs outside the region; however, some industries entered the county, creating a slight economic boom. An egg-dehydrating plant and a shoe manufacturing facility opened, employing many local citizens. While the financial outlook for the county improved, more than 1,200 young men were called to war, with fifty-nine killed in service.

Black River Vocational-Technical School opened in 1973 and evolved into a technical college over the next several decades. Located in Pocahontas, Black River Technical College offers both transfer and technical programs to students in the early twenty-first century.

Pocahontas resident Ed Bethune represented the Second Congressional District from 1979 to 1985. State senator Nick Wilson represented the county and other nearby areas for almost thirty years before being convicted of racketeering in 2000.

In twenty-first century Randolph County, lowland farmers export rice, soybeans, corn, and other grains, while cattle ranches and poultry houses dominate the uplands. One large employer, Pinnacle Frames and Accents, produces picture frames and albums. The wooded terrain, five rivers, and many smaller streams attract fishermen and hunters of deer, duck, and turkey to the region.

Randolph County contains several points of interest. Davidsonville Historic State Park interprets the life and death of Davidsonville, the 1820s-era Rice-Upshaw House still stands near Dalton, and the Maynard Pioneer Museum celebrates the early settlers. Pocahontas houses the restored 1875 courthouse; the Century Wall monument, a celebration of influential twentieth-century Americans; and the Eddie Mae Herron Center, a refurbished African-American school functioning as a community center and interpretative site. Other sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places include the Marr’s Creek Bridge, the Old Union School, and the Cedar Grove School No. 81.

For additional information:

Cook, Regina, et al. History of Randolph County, Arkansas. Dallas: Curtis Media Corp., 1992.

Dalton, Lawrence. The History of Randolph County. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithographing Company, 1946.

Dollar, Clyde. An Archaeological Assessment of Historic Davidsonville, Arkansas. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1977.

Randolph County, Arkansas: A Pictorial History. Sikeston, MO: Acclaim Press, 2006.

Stewart-Abernathy, Leslie C. The Seat of Justice, 1815–1830: An Archeological Reconnaissance of Davidsonville,1979. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1980.

Derek Allen Clements

Pocahontas, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Ed Bethune

Ed Bethune  Biggers Street Scene

Biggers Street Scene  Black River Technical College

Black River Technical College  Maynard Pioneer Museum

Maynard Pioneer Museum  Pocahontas Courthouse Square

Pocahontas Courthouse Square  Randolph County Courthouse

Randolph County Courthouse  Randolph County Courthouse

Randolph County Courthouse  Randolph County Courthouse

Randolph County Courthouse  Randolph County Heritage Museum

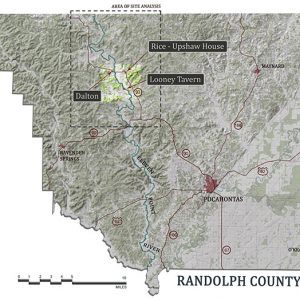

Randolph County Heritage Museum  Randolph County Map

Randolph County Map  Randolph County Sites

Randolph County Sites  John Randolph

John Randolph  Ravenden Spring

Ravenden Spring  William Looney Tavern

William Looney Tavern

Warm Springs and Ravenden Springs are often referred to as hot springs, but they are actually mineral springs. Ravenden has never been considered a “thermal spring” while Warm Springs is often incorrectly identified as such because of 1) its name; 2) prior publications–especially 1857’s David Dale Owen’s First Report of a Geological Reconnaissance of the Northern Counties of Arkansas. Reference is occasionally made to this report stating that the spring water was measured at 82 degrees F but in actuality the air temperature was 82 degrees F, the water was actually measured at 62 degrees F; and 3) a shallow recharge basin and significant surface water infiltration that can create instances in which the water feels tepid or warm to the touch.