calsfoundation@cals.org

Lawrence Brooks Hays (1898–1981)

Lawrence Brooks Hays was a twentieth-century political, civic, and religious leader in Arkansas. He was one of the most influential members of the state’s congressional delegation after World War II and one of the few laymen to serve as the president of the Southern Baptist Convention. While he often referred to himself as a politician, his wife thought the label that best described him was “Arkansas social worker.”

Brooks Hays was born on August 9, 1898, in London (Pope County) at the base of the Ozark Plateau. His father, Steele Hays, was a schoolteacher who later became a prominent lawyer, and his mother, Sallie Butler Hays, was also a schoolteacher. Brooks grew up in Russellville, the seat of Pope County, where his early life was steeped in the culture of the Southern Baptist Church and the Democratic Party, two institutions to which he would hold lifelong devotion and allegiance. Hays attended the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) from 1915 to 1919, where he was a leader in many campus organizations, graduating Phi Beta Kappa with a BA degree. At UA, he met Marion Prather, whom he eventually married on February 2, 1922. They had two children, a son and a daughter. As a member of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), the summer after his junior year he received military training at Camp Pike in Pulaski County during World War I, but he was discharged soon after the 1918 armistice. From 1919 to 1922, he attended George Washington University Law School in Washington DC while working full time for the Treasury Department.

Upon returning to Arkansas, he joined his father’s law practice and then secured an appointment as assistant state attorney general in 1925. Thereafter, he became an active leader in the Little Rock (Pulaski County) community, joining civic groups such as the Freemasons, the Lion’s Club, and the Urban League. Hays became a leading layman of the Second Baptist Church, where he led a Sunday school class that attracted hundreds of men from Protestant congregations, which became famous as the “Brooks Hays Class.” He was ultimately elected president of the Southern Baptist Convention for consecutive terms in 1957 and 1958.

Hays began his formal political career when he ran for and lost two consecutive close races for governor of Arkansas in both 1928 and 1930. In 1932, however, he was easily elected as a Democratic National Committeeman, then a prestigious statewide elected position. In 1933, he sought a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives from the Fifth Congressional District in a special election. Winning a plurality of votes in the runoff election, Hays’ victory was stolen from him, however, after skullduggery committed in Yell County ensured the victory of his opponent, fellow Democrat David D. Terry. After he lost a legal protest in federal court, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Hays as legal counsel to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In this capacity, Hays often represented impoverished sharecroppers in the Delta and worked in other labor and welfare issues.

In 1942, Hays was elected to the U.S. Congress, finally winning the Fifth District seat. His first notable work was an inspection tour of Allied-held territory in Europe after the successful Normandy landings on D-Day in 1944. In the U.S Congress, Hays was a leading Democratic legislator for eight terms. He cosponsored the GI Bill of Rights and was also the House sponsor for the International Exchange Program created by Senator J. William Fulbright. He also served as a delegate to the United Nations and became a ranking member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

As the civil rights movement emerged in the postwar period, Hays articulated the political ideology known as “Southern Moderation.” In 1949, he introduced the ill-fated Arkansas Plan as a legislative package designed to find a compromise to the increasingly heated civil rights debates that threatened to divide the Democratic Party. The plan sought to provide basic guarantees to secure African American voting rights, alleviate discrimination in voting, and prosecute lynch mobs. The plan, however, did not challenge segregation. He also served on the pre-platform committee at the 1952 Democratic National Convention and the platform committee in 1956, co-authoring weak and ineffective civil rights planks. Hays’s efforts to find a solution to the controversy satisfied neither civil rights activists nor intransigent segregationists. He failed because he never challenged the basic structures of Southern white supremacy. He voted against the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the first of its kind since Reconstruction. He formally denounced Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954)—which required the desegregation of public schools—when he signed the 1956 Southern Manifesto, though he later admitted that this decision was a mistake. Hays’ book A Southern Moderate Speaks (1959) argued that the improvement of Southern race relations would be best achieved through Christian churches. Nonetheless, civil rights workers believed that his methods only prolonged Jim Crow. Hays, however, was instrumental in breaking down racial and denominational barriers in Southern religious life. He helped initiate steps toward desegregation of the Southern Baptist Church, and then later became the first leader of his denomination to meet formally with the pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church.

The crucible of Hays’s political career was the Little Rock Central High School desegregation crisis of 1957–58. At the height of the crisis, Hays arranged the conference between President Dwight Eisenhower and Governor Orval Faubus at Newport, Rhode Island. The meeting ultimately failed, however, after Faubus refused to remove the Arkansas National Guard and allow the famous “Little Rock Nine” to matriculate at the school. Hays’ efforts to reconcile state and federal officials proved detrimental to his career. In his bid for reelection in 1958, Hays was defeated by the Little Rock ophthalmologist Dale Alford, a militant segregationist running as an independent, in an eight-day write-in campaign in the general election. Alford used legally questionable stickers attached to ballots, as well as other irregularities, to achieve this major upset.

After his forced retirement from Congress, Hays accepted a series of presidential appointments, first to the board of the Tennessee Valley Authority under Eisenhower, then as Undersecretary of State for Congressional Affairs and Special Assistant to presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. He tried a comeback to electoral politics in 1966, unsuccessfully running for Arkansas governor. In 1968, Wake Forest University recruited Hays to direct the newly established Ecumenical Institute, designed to facilitate Christian dialogue between Protestants and Catholics. The North Carolina Democratic Party recruited Hays for an uphill congressional race in 1972, which he lost handily, though he managed to maintain the party’s presence in the increasingly Republican district. He continued an active public life as a writer and lecturer. He also founded the Former Members of Congress, a powerful lobbying organization based in Washington DC.

Hays died on October 12, 1981, with services held in both Washington DC and Little Rock, and is buried in Russellville’s Oakland Cemetery.

For additional information:

Atto, William J. “Brooks Hays and the New Deal.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Summer 2008): 167–186.

Baker, James T. Brooks Hays. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1989.

Brooks Hays Papers, 1915–1978. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Day, John Kyle. “Bargain and Corruption, Arkansas Style: The Theft of the 1933 Special Congressional Election.” Central Arkansas Historical Review 2 (Spring 1999): 1–11.

———. “The Fall of a Southern Moderate: Congressman Brooks Hays and the Election of 1958.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Autumn 2000): 241–264.

Hays, Brooks. A Hotbed of Tranquility: My Life in Five Worlds. New York: Macmillan, 1968.

———. Politics is My Parish. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

———. A Southern Moderate Speaks. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959.

———. This World: A Christian’s Workshop. Nashville: Broadman, 1958.

“Principles and Politics: Documenting the Career of Congressman Brooks Hays.” Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries.

Stookey, Stephen M. “Brooks Hays: Civil Politician in an Unruly Parish.” Baptist History and Heritage 55.1 (2020): 19–31.

Williams, C. Fred. “Principles over Popularity: The Political Career of Congressman Brooks Hays.” Baptist History & Heritage 41 (Summer-Fall 2006): 89–98.

John Kyle Day

University of Missouri–Columbia

Hays Family

Hays Family  Brooks Hays Card

Brooks Hays Card  Lawrence Brooks Hays

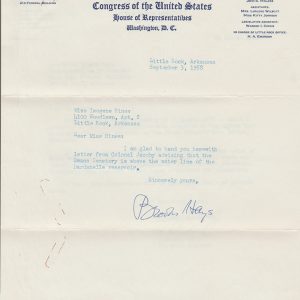

Lawrence Brooks Hays  Brooks Hays Letter

Brooks Hays Letter  Ben Laney with Congressional Delegation

Ben Laney with Congressional Delegation

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.