calsfoundation@cals.org

Insects

Insects account for over half of all species described thus far worldwide, and they are the dominant form of life in terrestrial environments. It is estimated that 35,000 to 40,000 species of insects live in Arkansas, including around 10,000 species of beetles, around 9,000 species of flies, nearly 8,000 species of bees and wasps, and around 5,000 species of moths and butterflies. The remainder make up small orders such as the bristletails, mayflies, dragonflies and damselflies, cockroaches, mantids, termites, stoneflies, grasshoppers and crickets, earwigs, stick insects, book and bark lice, chewing and sucking lice, and true bugs and lacewings and their relatives. It is still not uncommon to find species in Arkansas that are unnamed and new to the scientific world. This rich diversity has resulted from varied topography, a long history of favorable climate and habitats, and periods when the area was isolated from and then reconnected with other areas of North America.

The Arkansas insect fauna is typical of the North Temperate Deciduous Forest, which blankets eastern North America and has affinities with Europe and northeastern Asia derived from a time 180 million years ago when the continents were locked together. Most insects found in Arkansas can also be found outside the state’s borders. Some occur beyond the state’s boundaries but are confined to the Interior Highlands, which include the Arbuckle and Wichita mountains in Oklahoma in addition to the Ozark and Ouachita mountains, which are mainly in Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma. The Interior Highlands region is the only high ground between the Appalachian Mountains of the east and the Rocky Mountains of the west. Some species have disjunctive distributions, occurring in Arkansas and in some distant place, with gaps in the ranges. Endemic is the term for species occurring only within a defined area, such as the state of Arkansas. The Arkansas Ozark and Ouachita mountains are home to many endemic insect species. More than thirty have been documented, and new ones are added to the list frequently. The specialized habitats of these insects serve as possible keys to unlocking some bit of information about the natural history of the state. Many have close relationships with Appalachian species. Others have their nearest relatives living in western North America. Still others have their nearest relatives in Asia. The endemic species indicate that the Ozark and Ouachita mountains have provided safe haven for many life forms during geological periods when most of the rest of the continent was covered by seas or glacial ice and therefore not available for habitation by terrestrial species.

Geological and Evolutionary Background

Insect distribution patterns can be best understood in the context of Arkansas’s geological history. The area known as Arkansas was covered by seawater before the Pennsylvanian Epoch, at the beginning of the Carboniferous Period some 320 million years ago. During the Pennsylvanian, the Ozark Mountains rose above the surrounding epicontinental sea, and this hot, steamy area became habitable by insects. In 1859, Leo Lesquereux, working with the state geological survey, discovered a Pennsylvanian cockroach fossil near Frog Bayou in Crawford County. The area has been habitable ever since because it was never again covered with water or scoured by glacial ice. At about the same time, the Ouachita Mountains were growing, and a ridge connected them with the Appalachian Mountains for nearly 200 million years until the early Cretaceous Period. Early in the Cretaceous, epicontinental seas invaded and divided North America, separating the eastern and western parts of the continent. The Interior Highlands were islands in the epicontinental seas.

By the beginning of the Tertiary Period, some 63 million years ago, many of the insects that we recognize today had already evolved. In the Miocene Epoch, which began some 23.8 million years ago, the front range of the Rocky Mountains was thrust up, and Arkansas became drier due to the resulting rain shadow. Forests that once extended across North America were not able to survive in the rain shadow, and grasslands developed in their place. Arkansas’s mountain springs and streams and slightly cooler temperatures probably provided isolated refugia in which moisture- and cool-adapted insects could survive. Within the last million years, the Pleistocene glaciations have come and gone several times, removing most life forms from more northern regions, but never scouring Arkansas. However, insects were displaced southward and found sanctuary in the Interior Highlands. As the glaciers retreated, populations of some of the insects moved back northward, but others stayed. The populations eventually became isolated from each other and evolved into distinct species. It has been hypothesized that during the Wisconsinan glaciation, many species occurred throughout the forests of the southern-central and eastern United States. With retreat of the glaciers, some species that are adapted to cool, moist conditions found refuge in caves in warming southern lowland areas. Some cave insects are distributed almost totally south of the Wisconsinan glacial maximum.

Some aquatic species found refuge in isolated habitats with preserved environmental conditions that were more continuous before and during glaciations. Twenty-eight percent (twenty-five species) of stoneflies and twelve percent (twenty-seven species) of caddisflies are endemic to Arkansas. The Interior Highlands also contain a large number of widespread aquatic species that also occur east of the Mississippi River. These species may have continuous distributions, and they tend to be ecological generalists that survive in large rivers. Other widespread species have ranges that follow an open dispersal route across an area that would otherwise be impassible due to unsuitable habitat, such as the narrow band of uplifted terrain in the Illinois Ozarks. This area has sufficient stream gradients and suitable temperatures to permit east-west dispersal of many animal groups. A few species have discontinuous ranges, occurring in the Interior Highlands and in areas east of the Mississippi River.

Insects and Arkansas History

Insects have played an important role in Arkansas history since its first colonization. Mosquito-borne malaria caused untold suffering along with social and economic disorder. The creation of Arkansas Territory in 1819 brought numerous visitors to Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), where many inhabitants had malaria. The vector mosquito in Arkansas (Anopheles quadrimaculatus) was extremely numerous, likely to be found in houses and other structures, and able to breed for a long period each year. In the early 1940s, a quarter to a third of the people in many Arkansas communities had malaria, and a large portion of the population was self-medicating with quinine or chill tonics. Even as late as the 1940s, inhabitants of lowland areas of eastern Arkansas still used damp leaves, old rags, rubber, leather, and other materials to produce dense smoke to repel mosquitoes. Smudges were usually lit in the front yard near the porch in late afternoon. It was DDT and post–World War II spray programs that finally brought Arkansas mosquitoes and malaria under control. By the early 1950s, few if any cases of malaria were being reported. The dangers posed by all the insecticides released into the Arkansas environment for the control of malaria and its vector mosquitoes, however, may never be fully known.

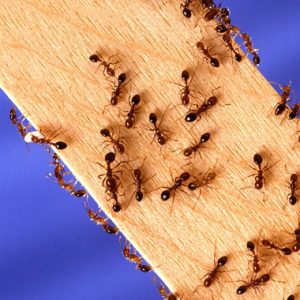

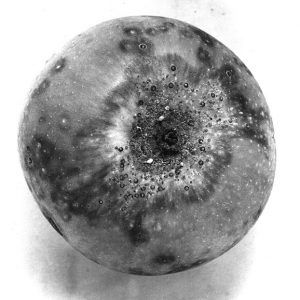

Many other pests have played important roles in the social and economic history of Arkansas, exacting a heavy cost in reduced production and environmental degradation due to pesticide usage. Early in the twentieth century, cotton was king, except in northwest Arkansas, where apple orchards abounded, and in the Grand Prairie area of southeastern Arkansas, where rice culture was beginning. The boll weevil entered Arkansas from the south in 1906 and was generally distributed over the state’s cotton-growing region by the end of 1921, taxing the economy of the state’s Delta region. By 1949, it was costing Arkansas growers a loss of more than $91 million worth of cotton, plus an enormous sum for insecticide applications. In more recent times, the Arkansas Boll Weevil Eradication Program has nearly removed this pest from the state. The codling moth and San Jose scale seriously hampered apple growing and soon contributed to the decline of the apple industry. The flooding of rice fields amplified the mosquito problem in the Delta region, while the rice water weevil claimed a good portion of the crop. It seems that wherever organic resources are concentrated, pest insects appear. Poultry houses harbor large populations of bed bugs. Pine forests are home to southern pine beetles. Subterranean termites infest wooden structures and now probably cause more economic injury than any other pest insect in Arkansas. New species are constantly arriving. Red imported fire ants have been expanding their range northward since the 1950s. The Japanese beetle, the most economically damaging pest of turf and landscape plantings in the eastern United States, arrived as larvae with nursery stock in the late 1990s and is now well established in the central and northwestern parts of the state. The European hornet was first detected in northern Arkansas in 1999. Formosan termites are on the state’s doorstep and may soon be the subject of grave concern. The Africanized honey bee was first detected in the southwestern part of the state in 2005, and, within two years, it was found as far north as Baxter County.

Research

The Division of Agriculture of the University of Arkansas System has responsibility for entomological research and extension activities. It maintains a statewide campus consisting of two parts, the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, which performs basic and applied research, and the University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service (UACES), which delivers appropriate technologies and information to industry, institutions, and individuals. Division faculty and facilities are located on several university campuses, regional research and extension centers, branch stations, and other locations, and a UACES office is located in each county. The division employs extension specialists in cotton, rice, field crop, veterinary, and urban insect pest management, as well as apiculture. The Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, headquartered on the UA campus in Fayetteville, shares faculty with the Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences.

Entomological instruction at what is now the Bumpers College began in 1873. The college’s Department of Entomology—the only one in the state—was founded in 1905, with the reorganization of the Department of Agriculture and the Experiment Station staff into a single entity. Early research efforts concentrated on insects found in fruit and cotton. Later staff worked on horseflies and mosquitoes. In the 1950s, the department continued to grow and expand as a result of increasing insect problems and the availability of DDT and other new insecticides. In the 1960s, new emphasis was placed on insect physiology and taxonomy, and the department’s insect collection grew. Research on rice, forest, and cotton insects was intensified. In the 1970s, funding became available for more work on cotton and soybean insects. Today, the department has specialists working on insects of rice, forests, fruits, vegetables, livestock, and poultry, in addition to mosquitoes and cotton and soybean insects. Scientists also work on insect genetics, insect/plant interactions, insect and mite systematic, and biological control of insect and plant pests.

The Arkansas State Plant Board was organized by George C. Becker, one of the early leaders of the Department of Entomology at UA. Among its many duties is the licensing of pest control operators. Arkansas was the first state with this licensing requirement, which set the stage for a responsible and honest pest control industry. The head of the Department of Entomology sits on the board. Today, the Plant Board, an agency within the Arkansas Agriculture Department, regulates insecticide use within the state, licenses pest control operators and inspects their work, inspects nurseries and plant shipments for presence of insect pests, enforces quarantines of pests such as sweet potato weevils and fire ants, and supervises detection surveys and some eradication efforts for such pests as Japanese beetles, khapra beetles, and Asian longhorn beetles. The board’s Pink Bollworm Section surveys for pink bollworms and enforces regulations implemented for the control of this pest. The Apiary Section registers apiaries, allocates pasturage rights to protect against over- or under-population of bees, and inspects and regulates apiaries for diseases and pests.

The Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission maintains a list of species vulnerable to extinction through human or natural threats. The state list of rare insect species includes four springtails, two dragonflies, two mayflies, nine stoneflies, one cricket, three bugs, twenty-nine beetles, twenty-nine butterflies (and skippers and moths), five caddisflies, and one bee. The American burying beetle was declared endangered by the federal government in 1989. In Arkansas, this species occurs in five counties in the western part of the state, mostly on federal lands such as Fort Chaffee Military Reservation and the Ouachita National Forest.

For additional information:

Allen, Robert T. “Insect Endemism in the Interior Highlands of North America.” Florida Entomologist 73 (1990): 539–569.

Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission. http://www.naturalheritage.org/ (accessed February 25, 2021).

Lancaster, Bob. The Jungles of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1989.

Lavers, Norman and Cheryl. 100 Insects of Arkansas and the Midsouth. Little Rock: Et Alia Press, 2018.

Lett, Becca L. “Biodiversity and Cold Tolerance of Dung Beetles in Cattle Pastures and Forested Habitats of Northeast Arkansas.” MS thesis, Arkansas State University, 2024.

Lincoln, Charles, and Lloyd O. Warren. A History of Entomology in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Department of Entomology, 1985.

Miner, Floyd D. “The Entomology Department.” Arkansas Farm Research 24 (1975): 10–11.

Moulton, Stephen R., and Kenneth W. Stewart. “Caddisflies (Trichoptera) of the Interior Highlands of North America.” Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 56 (1996): 1–313.

Plant Industries. https://www.agriculture.arkansas.gov/plant-industries/ (accessed February 25, 2021).

Poulton, Barry C., and Kenneth W. Stewart. “The Stoneflies of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains (Plecoptera).” Memoirs of the American Entomological Society 38 (1991): 1–116.

Robinson, Henry W., and Robert T. Allen. Only in Arkansas: A Study of the Endemic Plants and Animals of the State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

University of Arkansas Bumpers College of Entomology. https://entomology.uark.edu/index.php (accessed February 25, 2021).

Jeffrey K. Barnes

University of Arkansas Arthropod Museum

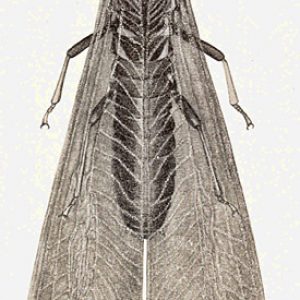

Antlion

Antlion  Antlion Pit Trap

Antlion Pit Trap  Bug Fest

Bug Fest  Codling Moth Damage

Codling Moth Damage  Cotton Boll Weevil

Cotton Boll Weevil  Cottonwood Borer

Cottonwood Borer  European Hornet

European Hornet  Fire Ant Stings

Fire Ant Stings  Fire Ants

Fire Ants  Honeybee, Official State Insect

Honeybee, Official State Insect  Japanese Beetle

Japanese Beetle  Male Diana Fritillarys

Male Diana Fritillarys  San Jose Scale

San Jose Scale  Southern Pine Beetle Damage

Southern Pine Beetle Damage  Spraying for Codling Moth

Spraying for Codling Moth  Termite Queen

Termite Queen

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.