calsfoundation@cals.org

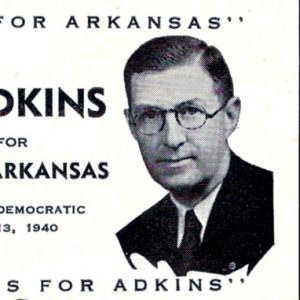

Homer Martin Adkins (1890–1964)

Thirty-second Governor (1941–1945)

Governor Homer Martin Adkins stands as a symbol of many Arkansans’ ambivalence about the growing power of the federal government in the mid-twentieth century and their resistance to attendant changes in the Democratic Party. Adkins’s clout as a factional leader during the 1930s derived from federal spending in the state, and his successes as governor had everything to do with the U.S. government’s massive investment in military facilities, defense production, and state bonds. But Adkins remained a self-described conservative, always ready to support states’ rights, such as when Democratic administrations in Washington DC and federal courts began to more actively support the civil rights of African Americans.

Homer Adkins was born on October 15, 1890, near Jacksonville (Pulaski County), the son of Ulysses Adkins, a farmer and merchant, and Lorena Woods Adkins. When he was ten, his family (including a sister) moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County), where he graduated from high school. Adkins subsequently attended Draughon Business College and also studied pharmacy. By age twenty-one, he had become a registered pharmacist and had gone to work in a Little Rock drugstore. Adkins joined the U.S. Army during World War I and eventually shipped out to France as a member of the Medical Corps. In the service, he met a nurse, Estelle Smith, whom he married in 1921. The couple had no children. After the war, Adkins worked in the building materials business in Little Rock.

Adkins developed an interest in politics early on. He had worked in Joseph T. Robinson’s 1912 gubernatorial campaign, apparently making a connection that would serve him well. At the height of the influence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in state politics, Adkins was elected Pulaski County sheriff, serving from 1923 though 1926. He later explained that he joined the KKK simply to secure its support, but the Klan’s racism and noisy opposition to “vice” remained Adkins hallmarks for decades. He became a partner in an insurance firm after stepping down as sheriff but was elected to Little Rock’s city council in 1929.

Adkins possessed a talent for remembering names and faces “that may have been unmatched in his time and place,” according to his obituary in the Arkansas Gazette. These political skills were put to work in Franklin Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential campaign, and with Senator Joseph T. Robinson’s backing, Adkins was consequently appointed Arkansas’s collector of internal revenue in 1933, placing him at the pinnacle of a patronage network that expanded considerably as Roosevelt’s New Deal multiplied federal positions in the state. The power this accorded Adkins was wielded in concert with Robinson and Governor Junius Marion Futrell—men distinctly more conservative than the president responsible for their good fortune. Adkins’s “federal faction” enjoyed an early victory in torpedoing Brooks Hays’s congressional candidacy in 1933. The bitterness that developed between Adkins and Hays’s supporter Carl Bailey yielded a prolonged factional feud. After Bailey was elected governor in 1936, he and Adkins became figures around which lesser politicians clustered.

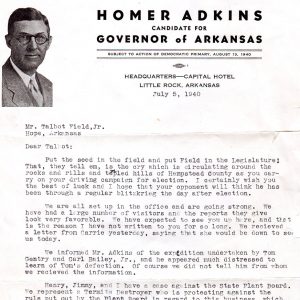

Adkins helped scotch Bailey’s bid for the U.S. Senate in 1937 by orchestrating John E. Miller’s independent candidacy. In 1940, he challenged Bailey more directly by resigning the collectorship and running for governor. Adkins challenged Bailey’s ambitions for a third term and campaigned against the governor’s plan for paying off Arkansas’s crippling highway debt. He won both the primary against Bailey and the general election against a hapless Republican opponent, H. C. Stump, by decisive margins.

Adkins had the good fortune to become governor just as the defense mobilization preceding American entrance into World War II began to lift Arkansas out of the Depression. But Adkins attended to unfinished business first. He scored what may ultimately have been a pyrrhic victory in his ongoing warfare with Bailey by sacking J. William Fulbright, whom Bailey had appointed president of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He also enacted his own plan to re-fund the gargantuan highway debt. A federal agency, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, eventually bought the whole of the $137 million bond issue, allowing the state to pay its obligations at lower interest rates and over a longer term. And as he had while sheriff of Pulaski County, Adkins—who neither smoked nor drank—waged war on vice, sending in the state police to crack down on gambling in Hot Springs (Garland County). He failed, however, to persuade legislators or voters to end horse racing there and dog racing in West Memphis (Crittenden County).

With Adkins’s encouragement, the federal government spent over $300 million on defense plants and military installations in Arkansas during the war. The state had money, citizens had jobs, and Republicans did not even field a candidate to oppose Adkins’s reelection in 1942. Yet prosperity brought its own species of turmoil—housing shortages, school closings, families tossed asunder. Few were uprooted so completely as the thousands of Japanese Americans interned in Arkansas, but Adkins had nothing to offer even the many citizens among them but the back of his hand. He resisted the placing of internees in the state at all, yielding only upon being promised that they would be closely guarded and driven from the state at war’s end. He preferred that Arkansas’s wartime labor shortage be dealt with by working German and Italian prisoners of war rather than by Japanese Americans leaving the camps. Adkins backed a 1943 law prohibiting anyone of Japanese birth or ancestry from owning property in Arkansas.

Adkins also resisted wartime strides made in black civil rights, becoming, historian Ben F. Johnson says, “the state’s most overtly racist governor in the modern era.” He decried the Roosevelt administration’s order officially banning racial discrimination in war industries as an encroachment on states’ rights. He even agitated for a constitutional convention to nullify both the nondiscrimination mandate and the Supreme Court’s 1944 Smith v. Allwright decision, which forbade the longstanding exclusion of African Americans from the Democratic primaries that determined who would hold office in Arkansas and other one-party Southern states. Insisting that his would remain a white man’s party, Adkins ultimately settled for a plan that would allow African Americans to vote for federal officeholders (the balloting most immediately subject to the courts’ scrutiny) but not for state officials, and that would prevent them from competing for Democratic nominations. When black Democrat John Marshall Robinson, in a bit of realpolitik, offered an endorsement of Adkins’s own bid for federal office in 1944, he spurned it, declaring, “If I cannot be nominated by the white voters of Arkansas, I do not want the office.”

Neither, Adkins declared in the same campaign, would he accept the endorsement of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), the labor federation whose money and manpower had become increasingly essential to the Democratic Party nationally. Adkins proved cagier when it came to labor than race, speaking soothingly of the generally less militant American Federation of Labor (AFL) as “progressively conservative and 100 per cent American”—in contrast to a “leftist” CIO beholden to “foreign-isms.” He allowed an “anti-violence” bill, which hemmed in unions’ use of strikes, to become law without his signature. But in refusing to veto the bill, he gave voice to the same anxieties conjured by Arkansans campaigning to ban labor agreements that required workers to join unions as a prerequisite for employment. Adkins said he did not want to give “a free hand to unscrupulous agitators who attempt to organize domestic and farm workers.” Like other Southern conservatives, he seemed destined to conflict with a Democratic Party that, at the national level, counted African Americans and union members among its most loyal constituents.

But Adkins wanted to go to Washington DC as a Democratic senator all the same. He had managed Senator Hattie Caraway’s reelection campaign in 1938 but challenged her in 1944, as did El Dorado (Union County) oilman Thomas Barton and J. William Fulbright, now a congressman. While Barton drew large crowds by renting Grand Ol’ Opry stars to serenade the electorate, the race ended in a face-off between Adkins and Fulbright. Adkins redbaited and racebaited Fulbright (who, by any honest accounting, was vulnerable on neither score). Yet Fulbright—enjoying the support of northwest Arkansas, university alumni, Adkins’s foes in Hot Springs, embittered Caraway and Bailey supporters, the CIO, and some Delta bosses—won a decisive victory.

After leaving office, Adkins, who had a farm west of Malvern (Hot Spring County), involved himself in a seed company, real estate, and eventually public relations. But his political career was not over. Indeed, the post-gubernatorial years had a symbolic importance all their own, vividly illustrating the strange bedfellows Arkansas politics often made. In this case, Adkins found himself bundled with Carl Bailey. Both supportedthe 1948 gubernatorial candidacy of Sid McMath, a man far more comfortable with the growing claims of organized labor and African Americans upon the Democratic Party but one who shared Adkins’s hostility toward Hot Springs boss Leo McLaughlin. Adkins secured him the support (albeit temporarily) of corporate giant Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L), and McMath appointed him administrator of the Arkansas Employment Security Division. He left this post in 1952 to aid McMath’s unsuccessful bid for a third term. Two years later, he backed Orval Faubus’s winning campaign for governor.

Adkins died of heart disease in Malvern on February 26, 1964, and is buried in Roselawn Memorial Park in Little Rock. Governor Faubus eulogized a man he took to be a kindred spirit, declaring that Adkins “stood four-square for constitutional government according to the philosophy of Thomas Jefferson, and opposed with vigor the usurpation of the rights of the states and the people by the federal government.”

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy, Willard B. Gatewood, and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Smith, C. Calvin. War and Wartime Changes: The Transformation of Arkansas 1940–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Patrick G. Williams

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

I think it is a shame that a school is named after such a racist person who was a member of the KKK.

Homer Adkins was my uncle. I hardly remember him, but I used to go with my parents to visit with him and Aunt Stelle. I would like to know more about him. I was told there was a church and a school named after him. When we went to see them, I was a small child; I am now 59. Uncle Homer had a dog that would go and get the mail for him, but before the dog would let him have it, Uncle Homer had to give him a piece of light bread. He let me give the dog the bread and the dog gave me the mail. He also had some goats in a pen in the back and told me that if I caught one, I could have it. Being a kid, that thrilled me. So while the grownups were visiting, I sneaked out back and got in the pen to catch a goat and one had me pinned in. I remember yelling for help and Uncle Homer came running out there and got me. My grandmother’s name was Margaret William Smith, and she and Aunt Stelle were related.