calsfoundation@cals.org

Dardanelle (Yell County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º13’23″N 093º09’28″W |

| Elevation: | 334 feet |

| Area: | 3.64 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 4,517 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | January 17, 1855 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

926 |

748 |

1,456 |

1,602 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,757 |

1,835 |

1,832 |

1,807 |

1,772 |

2,098 |

3,297 |

3,621 |

3,722 |

4,228 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4,745 |

4,517 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dardanelle, adjacent to the Arkansas River in northeast Yell County, was platted in 1847 and incorporated on January 17, 1855. The origin of the town’s name is open to conjecture.

European Exploration and Settlement

Several Native American tribes hunted in or inhabited the area, including the Osage, Caddo, and Cherokee. Thomas Nuttall’s 1819 journal described Cherokee people living in log cabins along the Arkansas River south of the Dardanelle Rock surrounded by cotton fields and peach and plum orchards. French exploration of the area was primarily limited to a few hunters who dared to infringe on Osage-claimed lands.

There are many explanations for the town’s name. Some have speculated that the 300-foot-high rock face at the river’s edge reminded early explorers of the Dardanelles in Turkey, or while others insisted that the early French coureur de bois and holder of a 600-acre Spanish land grant in the area, Jean Baptiste Dardenne, is the source of the town’s name. However, Jean Batiste Dardenne lived much further to the west from 1797 until approximately 1806, and his land grant was not even perfected while he was alive. Dardenne’s father had a successful trading operation and was a major landowner at Arkansas Post.

The name of the community is spelled various ways in early official documents and travelogues: Dardanville, “the Dardanelle Rock,” “the Dardonelle,” Dordunoville, and Derdanai. However, these various names are possible phonetic attempts to render the French phrase dors d’un oeil, meaning essentially “sleep with one eye open,” reflecting the possibility of danger in the area.

As the last of the Native American inhabitants were removed to Indian Territory, Dardanelle’s population slowly grew and was composed primarily of farmers and a few artisans and merchants. Census records for 1830 and 1840 reported that Dardanelle Township’s population comprised 36 and 39 heads of household, respectively.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

By 1803, Dardanelle was a contentious area, with Cherokee and Caddo groups engaging in sporadic conflict. The United States sent Major James Lovely to the area as its first Indian factor in 1813, followed by Reuben Lewis in 1817, David Brearley in 1820, and Major Edward W. Duvall in 1823. Also in 1823 Robert Crittenden met with Cherokee leaders for the Treaty of Council Oaks to discuss land ownership and borders but no consensus was met. With his brothers, Charles and Pearson, David Brearley opened the first store in Dardanelle, and his son, Joseph H. Brearley, platted the town in 1847 and, in 1851, donated lands for Brearley Cemetery just south of town.

Dardanelle became an important river town and emerging trade center during the antebellum era, receiving weekly steamboat visits from New Orleans, Louisiana; Memphis, Tennessee; and Little Rock (Pulaski County). Dardanelle’s “boomtown” reputation was aided by its trade in rum, gin, and cotton. By 1860, the town had three taverns, several mercantile businesses and cotton gins, three churches (Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian), a weekly newspaper, a doctor, a school, several attorneys, and a Masonic lodge. By 1860, the town had 239 white residents and seventy-four slaves. Settlers from Tennessee and North Carolina were most prevalent. The surrounding rich farmland was worked by yeoman farmers primarily and a few large planters. Slavery was common on the surrounding farmlands—the 1860 Census records 869 slaves in Yell County, in addition to Dardanelle’s seventy-four. The 1823 military road between Little Rock and Fort Smith (Sebastian County) ran through Dardanelle, although the Arkansas River remained the primary means of transportation. In 1860, Dardanelle was linked to Little Rock and Fort Smith by telegraph.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Civil War action destroyed parts of Dardanelle. Given its Arkansas River location, Dardanelle became a focal point of military activities as both Union and Confederate troops attempted to secure control of this strategic river link. By October 1862, Union troops had control of Dardanelle, and several attempts by Confederates to retake the area between 1862 and early 1865 left much of the town in ruin. These included a skirmish in fall 1863, the capture of the city in early summer 1864, and another skirmish in late summer 1864. Some families left the area to avoid the bushwhacking activities and having their crops and food stores requisitioned by Union troops. By 1866, the population of Dardanelle was 266. Approximately 100 Dardanelle men served in the Confederate army, but, by 1862, they were mostly serving east of the Mississippi River. The town’s remaining inhabitants were on their own enduring periodic military skirmishes and severe food shortages and deprivation.

During the postwar era, Dardanelle, like most of the South, experienced violence. On December 25, 1869, a group of white and African-American citizens were celebrating Christmas with whiskey and firearms. As the celebrations became increasingly rowdy, Andrew Chandler, a black store owner, sent for Holland Musteen, a white man with a notorious reputation for murder in Yell and Franklin counties. Before Musteen arrived, Chandler was shot at by an intoxicated white man and fled his store accompanied by other black revelers; by early evening, a white mob had forced all black residents to leave town. Meanwhile, Musteen arrived and allegedly shot and killed Port Jones, a white man who had previously been a member of a posse searching for Musteen. In May 1870, Musteen was found innocent and, in September 1871, was injured as he rode with a sheriff’s posse pursuing an escaped black jail inmate. To refer to this violence as a race riot would be an overstatement, but these events do demonstrate the extreme tensions that existed between black and white citizens and the propensity toward violence that existed during the Reconstruction era in and around Dardanelle.

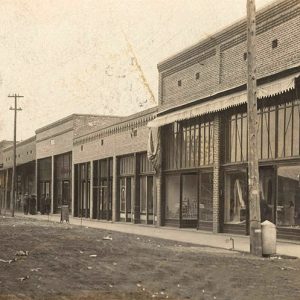

During Reconstruction, the town began to rebuild. A hardware store opened in 1868, a wagon and implement business opened in 1870, two new hotels opened in the early 1870s, and new immigrants arrived, primarily from Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

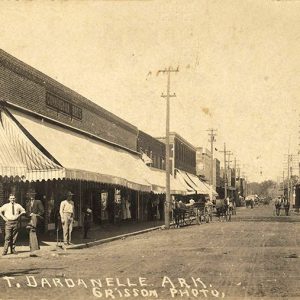

Dardanelle soon grew into a major trading center for Yell County. River-based trade continued to promote commercial activities. A post office was established in 1833, a county courthouse for the northern half of Yell County was erected in 1878, and an ice plant—the first established in Arkansas—went into operation in 1888. The first public school was built and opened in 1885. Numerous new mercantile businesses opened, and the first bank in town was established in 1895.

From 1873 through the late 1880s, Dardanelle experienced new immigration as numerous Slovak, Moravian, Bohemian, and Czech families arrived. Mainly farmers and coal miners, these new immigrants expanded ethnic diversity into the town’s primarily Scotch-Irish and English residents, introducing new languages and religions.

On September 10, 1881, two white men named J. F. Bruce and John Taylor were lynched in Dardanelle for having allegedly murdered a man. Later that year, on November 26, 1881, Jim Holland was also lynched for murder.

In October 1890, Dardanelle’s pontoon bridge, the longest in the world at the time, was opened. The floating bridge was financed by tolls of five cents per foot passenger round trip and twenty-five cents loaded wagon round trip.

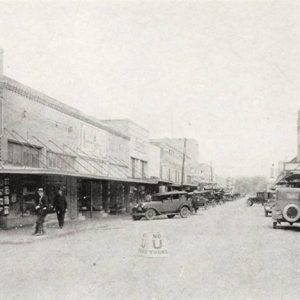

Early Twentieth Century

In 1910, electric service was initiated. In August 1916, a telephone cable across the Arkansas River linked Dardanelle to Russellville (Pope County). In 1914, a new county courthouse was erected at a cost of less than $25,000. During World War I, Dardanelle raised $118,150 from two major Liberty Bond drives, $32,650 above the goal. During the war, 167 Dardanelle citizens served in the military, and two were killed in action. In 1927, the town paved all its streets. In 1930, a new bridge was built across the Arkansas River, and the Dardanelle Confederate Monument was moved from its original location to the lawn of the Yell County Courthouse.

The Flood of 1927 wreaked havoc in and around Dardanelle, given the related flooding of the Arkansas and other area rivers. As flood waters enveloped the entire surrounding countryside and covered the low-water areas in town, Dardanelle lost electric power on April 14, 1927; three anchorage towers of the pontoon bridge were swept away at a replacement cost of $2,000 each—two were ultimately found at Morrilton (Conway County) and the third was destroyed near Little Rock; telephone service to Fort Smith was lost; and the town was completely surrounded by water. Dardanelle was filled with refugees from the countryside who escaped twenty-five-foot overflows. By April 21, 1927, the Arkansas River at Dardanelle crested at thirty-three feet, and citizens nervously threw themselves into a variety of relief efforts, some of which lasted for months. By June 1927, the American Red Cross had expended $10,562.49 in Yell County, private citizens had donated hundreds of dollars to relief efforts, health threats had increased due to excessive water pooling, and levees had been severely damaged.

As the trade center for an agricultural area, the town had already been negatively affected by the depressed cotton market of the 1920s. Between 1920 and 1930, the number of farms had declined by eighteen percent. The Drought of 1930–1931 caused additional financial stress. During the Depression, Dardanelle public schools operated on a reduced yearly schedule and paid teachers in credit warrants redeemed by only the Dardanelle Mercantile Company. By late 1930, one bank closed, and the Red Cross was asked to aid farmers with seed for gardens and pastures. By 1931, the local Rexall druggist, one Mr. Cinger, was supplying free medicine to the needy. The National Recovery Administration program was well received, and local merchants proudly displayed its “Blue Eagle” emblem. In 1939, the Federal Writers’ Project commissioned a Brooklyn artist, Ludwig Mactiarian, to paint a mural in the Dardanelle Post Office. The mural remains today, one of seventeen such works still existing in Arkansas.

World War II through the Modern Era

The 153rd Arkansas National Guard Unit from Dardanelle was activated in 1940 and spent five years in the Aleutians. During World War II, 239 citizens served in the military; fourteen were killed.

On October 26, 1941, a tornado killed seven citizens, demolished forty homes, damaged numerous businesses and homes, and caused $100,000 in damage. In November 1941, the Arkansas River flooded, reaching 32.1 feet, the highest river level since April 1927. The 1941 flood caused 108 refugee “county” families to evacuate to Dardanelle for ten days, and 50,000 bushels of corn were destroyed. In February 1943, 12,000 acres of Dardanelle Bottoms were under water; 200 families were evacuated, mostly by boats sent from Dardanelle; and twenty-seven families were marooned. With the construction of the Dardanelle Lock and Dam completed in 1969, part of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, flooding was controlled.

During the 1964–65 school year, Dardanelle schools desegregated after the high school in Morrilton to which African American students had been bussed raised its tuition rates.

By the 1960s, a fundamental agricultural transition was under way involving a decline in row crop production (especially cotton) and a shift to livestock production. The poultry industry soon became the primary agricultural activity and employment source. In 1965, Arkansas River Valley Area Council (ARVAC) was formed to serve a low-income citizens in a nine-county region in rural central Arkansas. Their main office is in Dardanelle. In the 1990s, Hispanic immigration increased. As of the 2010 census, Hispanics represented 36.1 percent of the population, while African Americans numbered 3.7 percent and Asian Americans 0.6 percent.

Dardanelle was one of many Arkansas locations affected by the Flood of 2019.

Attractions

The Dardanelle Agriculture and Post Office is one of nineteen locations in Arkansas where Depression-era post office art may be viewed.

Famous Residents

Several Dardanelle citizens have achieved national prominence, including Bonnie Brown Ring, a member of the 1950s country music group the Browns; John Daly, a professional golfer; James Lee Witt, former director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) during the administration of Bill Clinton; Henderson Madison Jacoway, U.S. congressman from 1911 to 1923; and Tom Cotton, a U.S. senator. Jesse Cleveland Hart served on the Arkansas Supreme Court, first as associate justice and then as chief justice. J. R. Gray was a painter, illustrator, sculptor, and graphic designer who grew up in Dardanelle. Charles T. Davis, the first poet laureate for the state, was born in Dardanelle.

For additional information:

———. “Dardanelle and the Indian Removal.” Yell County Historical & Genealogical Association Bulletin 44 (No. 2, 2019): 11–21.

Banks, Wayne. History of Yell County, Arkansas. Van Buren, AR: Press Argue, 1959.

Gleason, Mildred Diane. Dardanelle and the Bottoms: Environment, Agriculture, and Economy in an Arkansas River Community, 1819–1970. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2017.

Gravely, Ernestine Hudlow. “Fabulous Dardanelle.” Arkansas Gazette. Sunday Magazine. July 4, 1948, p. 1.

History of Yell County Vertical Files. Arkansas River Valley Regional Library, Dardanelle, Arkansas.

Yell County Historical and Genealogical Association. Yell County Heritage: A History of Yell County. Bedford, TX: Curtis Media, Inc., 1997.

Mildred Diane Gleason

Arkansas Tech University

Some of the members of the Ladies Missionary Society of the First Presbyterian Church were from “the best families” and had never worked at anything more strenuous than embroidery or flower arrangement, but in the early twentieth century, they began a fundraising drive to build a new church. They did everything from selling soap to harvesting peaches. When Calvin Batson, a prominent farmer and member of the church, jokingly suggested that he would give his wife and the other ladies a job picking cotton, they donned sunbonnets and headed for the field. The business houses closed their doors for the day, and the men turned out in a body to watch them pick. The gentlemen cheered the ladies on from their seats on spilt rail fences, while leisurely eating their picnic dinners from lard buckets. Tom Grissom, the town photographer, made a photo of the event which appeared in numerous newspapers and magazines, some with a national circulation. The picture caught the eye of Ferdinand T. Hopkins, a New York City philanthropist, who subsequently sent a sizeable donation of money. Somehow the ladies thought he was a member of the famous Hopkins family who built the Johns Hopkins Hospital, when in actuality he was the head of Gouraud’s Toilet Preparations, a ladies nostrum firm whose best seller was Mother Sill’s Seasick Remedy. Of course, all of those ladies are now long dead, but they went to their graves thinking that Mr. Hopkins was from a most prominent Eastern family, instead of being a seller of medications of “unmentionable purpose.”

I spent some of my young years in Dardanelle. In the early 1950s, my dad was pastor of First Baptist Church and headed up an anti-liquor drive. I remember going to a park called “Twin Oaks” for festivals and ceremonies. And the bad storms, too! It was a pleasant time, though. We moved to North Carolina in ’53, where I have remained since. I have often thought I might come back to Dardanelle and hope to do so for a visit yet again. I’m almost seventy now. Probably no one would remember us. I was a bratty little preacher’s kid of six years old back then! The church back then looked like a castle with a single parapet. The fire hydrant where I used to ride my trike is still on the corner, and the store on the opposite corner is still there in some form. It caught fire and burned in ’52(?) and was rebuilt. I still have a picture of me and Daddy, with his ’39 Ford sticking out of the garage across the street when it was being serviced that day.