calsfoundation@cals.org

Back-to-Africa Movement

The Back-to-Africa Movement mobilized thousands of African-American Arkansans who wished to leave the state for the Republic of Liberia in the late 1800s. Approximately 650 emigrants left from Arkansas, more than from any other American state, in the 1880s and 1890s, the last phase of organized group migration of black Americans to Liberia.

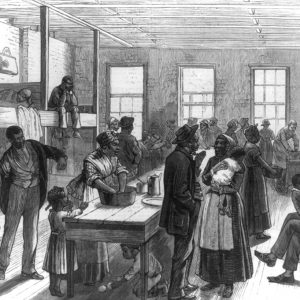

As early as 1820, black Americans had begun to return to their ancestral homeland through the auspices of the American Colonization Society (ACS), an organization headquartered in Washington DC, which arranged transportation and settlement. The ACS founded the Republic of Liberia in 1847, with its flag and constitution emulating American models, and nearly 13,000 redeemed slaves and free blacks had settled there before the Civil War. With the Civil War and abolition of slavery, the Back-to-Africa movement declined. However, interest in an African migration rekindled after Reconstruction ended and conditions for black Americans worsened in the late 1870s.

In several Delta counties of eastern Arkansas, white Democrats used extraordinary measures during the 1878 elections to keep African Americans from voting. In Phillips County, which was approximately seventy-five percent black, Democrats even stationed a heavy cannon in front of the main black polling place. Anthony L. Stanford, a black physician and Methodist preacher who also served as Phillips County’s Republican state senator, contacted the ACS, requesting assistance with emigration of a number of black citizens to Africa. In 1879, he led twenty-three residents of Phillips County to Liberia, and another 118 emigrants followed the next year from Phillips and Woodruff counties. Whereas Phillips County had polled a Republican majority in the 1876 presidential election, by the gubernatorial election of 1880, only ten Republican votes were cast in the county that had more than 15,000 black residents. Clearly, the Back-to-Africa movement was motivated by the deterioration in status of black citizens in the Delta in the late 1870s.

Conditions improved somewhat in the 1880s. Black men appear to have regained the franchise in the 1882 elections, and black Republican officials were elected to local offices in Delta counties through the rest of the decade. The 1880s also saw a massive in-migration as African Americans from the Deep South, especially South Carolina, fled their own oppressive conditions and looked to Arkansas as a place of plentiful work and cheap land. The 1880s seemed to be a time of promise for black Arkansans, and interest in African emigration waned but never went away. The Reverend Henry McNeal Turner of Atlanta, the foremost advocate nationally for African emigration, was elected bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in 1880 and was appointed to the eighth district, composed of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Indian Territory. Throughout the 1880s and early 1890s, Turner made yearly trips to Arkansas to preside over annual church meetings, and he always used the pulpit to promote emigration and missions to Africa. In 1886 and 1887, an African man, self-proclaimed “professor” Jacob C. Hazeley, traveled around the state giving lectures accompanied by picture displays about Africa. Hazeley encouraged interested parties to apply for emigration to the ACS. A farm family from Lee County and a schoolteacher from Fort Smith (Sebastian County) emigrated to Liberia in 1882. Three more left from Conway County in 1883, a family of eight from Phillips County emigrated in 1887, and a Faulkner County family of eight moved to Liberia in the spring of 1889.

However, it would be the return of political and racial violence in the late 1880s and early 1890s that made Liberia fever rage through black precincts of Arkansas. In the 1888 and 1890 elections, the Democratic Party faced opposition by a biracial alliance of the rural poor with the cooperation between the agrarian populist movement and the Republican Party. To win the elections, fraud and terror tactics eclipsed those used in 1878 in degree and scale. The Democratic-controlled state legislature passed the Election Law of 1891 aimed at disfranchising black and poor white voters (followed the next year by a poll tax). In addition, numerous Jim Crow laws aimed at enforcing segregation began to be passed. In the years that would follow disfranchisement, some of the most horrific lynchings in American history occurred in Arkansas.

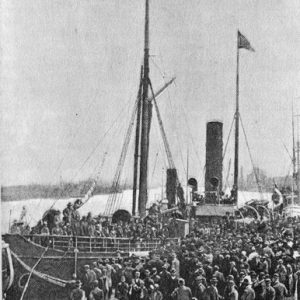

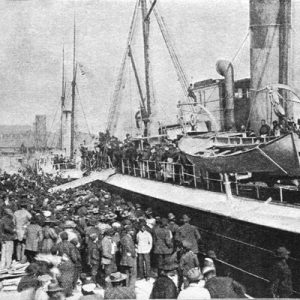

In response, black Arkansas sharecroppers and small landowners flooded the ACS office in Washington with letters begging for passage to Africa. As more information circulated back to Arkansas, interest only swelled. Would-be emigrants formed at least forty “Liberia Exodus” clubs that elected officers and held regular meetings, often disguising their true purposes from white neighbors hostile to the movement. Applications for emigration came in from the majority of Arkansas’s seventy-five counties, but interest was particularly keen in areas where political conflict was most intense—in Woodruff, St. Francis, Lonoke, and Jefferson counties in east-central Arkansas and the Arkansas River Valley from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Atkins (Pope County). In Conway County alone, which experienced some of the most spectacular political violence, nearly 1,500 African Americans, about twenty percent of the county’s black population, formally applied to emigrate to Liberia. Most of the emigrants sent by the ACS to Liberia in the early 1890s hailed from Arkansas, including nearly 100 from Morrilton (Conway County) and Plumerville (Conway County) and forty-four from Little Rock and Argenta (now North Little Rock in Pulaski County). A group of thirty-four would-be emigrants from Woodruff County sold their possessions and traveled to New York City in 1892 to beg unsuccessfully for passage to Africa. Their unexpected arrival created a refugee crisis for the ACS, leading it to end its seventy-five-year long resettlement program. The society got out of the emigration business just at the time demand was greatest in Arkansas. To address this interest, some white businessmen in Birmingham, Alabama, formed a company that transported to Liberia more than 200 Arkansans, mostly from Jefferson, St. Francis, and Lonoke counties, in three voyages between 1894 and 1896. A few additional black Arkansans booked commercial passage on steamers that traveled to Liberia from New York via ports in Europe. The interest in Africa spilled over into missionary work. Approximately a dozen black Arkansans and their families traveled to Africa in the 1890s as missionaries, a number representing nearly a quarter of known black missionaries to Africa in that decade.

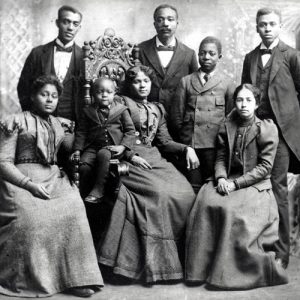

For the black Arkansans who emigrated, their African Promised Land brought great challenges and some rewards. The Republic of Liberia granted each emigrant family twenty-five acres of free land and settled most of the Arkansas arrivals together in two communities, Brewerville and Johnsonville, a few miles into the interior from the capital, Monrovia. In the heart of the tropics and one of the wettest places in Africa, Liberia hosted a variety of diseases, especially potent strains of malaria that ravaged the emigrant population. People struggled with illness just when they had the most work to do—clearing land, planting crops, and building homes. Settlers had to adjust to new foods and lifestyles and learn to grow a new cash crop, coffee, instead of cotton. The Arkansas emigrants of 1879 and the 1880s prospered through coffee cultivation. However, the coffee trees planted by settlers of the 1890s began to produce berries just in time for the cataclysmic drop in coffee prices, as production in Brazil began to glut the world market in the late 1890s. Several Arkansas emigrants returned to America; perhaps more wished to return but lacked the money for passage. But many of these new Liberians apparently were pleased with their new home. In the words of one Arkansas settler, William Rogers, who wrote back to family in Morrilton, Liberia was “the colored man’s home, the only place on earth where they have equal rights.” What Rogers liked best about Liberia, he said, was that “there are no white men here to give orders; and when you go in your house, there is no one to stand out, and call you to the door and shoot you when you come out. We have no foreman over us; we are our own boss. We work when we want to, and sit down when we choose, and eat when we get ready.” Some of the Arkansas families became prominent in the black republic. Victoria David Tolbert, Liberia’s former first lady whose husband, President William Tolbert, was murdered in the violent coup of 1980, was the daughter of Isaac David, who left Little Rock in 1891 with his family at the age of five.

For additional information:

American Colonization Society Records. Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington DC.

Barnes, Kenneth C. Journey of Hope: The Back-to-Africa Movement in Arkansas in the Late 1800s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Redkey, Edwin S. Black Exodus: Black Nationalist and Back-to-Africa Movements, 1890–1910. Yale University Press, 1969.

Patton, Adell, Jr. “The Back-to-Africa Movement in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 51 (Summer 1992): 164–177.

Kenneth C. Barnes

University of Central Arkansas

Today, we are grateful for the sacrifices of those who began the Back to Africa Movement. They made possible the connection we now enjoy. However, we recognize that today we do not need a movement like that envisioned by our forefathers. We now know that our freedom and respect is also linked to the freedom (independence) and respect of the African countries. What is needed today is a “BACK AND FORTH TO AFRICA MOVEMENT” where we intimately exchange people, technology, and support. Africa’s best and brightest should also come to the U.S. and return with the knowledge and experience to build Africa. This is a new day, and exciting times to be AFRICAN!

I’m researching the names of the families that went to Liberia from Arkansas. It is believed that my great-grandmother is among those names. It was my great-grandmother and two of her children.