calsfoundation@cals.org

Marshall (Searcy County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º54’32″N 092º37’52″W |

| Elevation: | 1,050 feet |

| Area: | 4.07 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 1,329 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | June 18, 1884 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

160 |

278 |

260 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

558 |

749 |

638 |

822 |

1,189 |

1,095 |

1,397 |

1,595 |

1,318 |

1,313 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,355 |

1,329 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marshall is the county seat and market town for poor and rural Searcy County, which contains 23,372 acres of the Buffalo National River and its surrounding lands, and 31,286 acres of the Ozark National Forest. Its only sustained industry has been timber processing. Beyond that, it is dependent upon cattle and the tourism brought in by the Buffalo National River. Mostly destroyed during the Civil War, Marshall grew slowly during the nineteenth century. The Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad sped Marshall’s growth from 1905 to 1910, but the post–World War I slump hit Searcy County’s and Marshall’s industries hard. Between spurts of economic activity and a series of celebrations, such as the Strawberry Festival from the late 1940s to mid-1980s and a genealogy fair for North Arkansas since 1990, Marshall has become a quaint place for quiet retirement. Marshall’s significance lies in its survival as a mountain county seat after challenges such as Civil War anarchy, devastation of mining and timber industries, a bankrupt railroad, failed small local and outsider-owned industries, and aggressive environmentalists.

Pre-European Exploration through Early Statehood

Archaeological evidence indicates that the various springs in and around Marshall attracted Native Americans during the Archaic Period (9500 BC to 650 BC), but there is little evidence of Native American settlement since the Archaic Period. Later Native American settlement appears in Searcy County’s creek and river bottoms, but not on the side of the mountain where Marshall lies. Upon American settler contact, all of Searcy County was in the Osage sphere of influence. In 1808, the Osage sold all of their land in Arkansas to the U.S. government. The government established the Cherokee Reservation in north central Arkansas in 1817, which contained all of what is now Searcy County. It lasted from 1817 to 1828, when the Cherokee were moved to what is now Oklahoma. There were Cherokee, Shawnee, and Miami-Delaware settlements in what is now Searcy County during and immediately after the Cherokee Reservation was there, but there is no evidence that they lived where Marshall is located.

On November 5, 1835, the Arkansas territorial legislature established Searcy County to include the area now roughly covered by present-day Marion and Searcy counties. In September 1836, the name was changed from Searcy to Marion.

On March 8, 1836, settlers living in what were then Pulaski, Conway, Van Buren, and Searcy counties petitioned that a mail route be established from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to the Searcy County courthouse, now Yellville (Marion County), with a post office at Bear Creek (Searcy County), with state senator Charles R. Saunders as postmaster. Present-day Searcy County was created on December 13, 1838, from the southern part of Marion County, and the county seat was later established at Lebanon on Bear Creek. In 1856, voters elected John H. Marshall, James W. Gray, and Littleton Baker as commissioners to locate another site for the county seat, though their exact reasons for doing so are unknown. The proposed site was on a bench of the Devil’s Backbone Mountain at Raccoon Springs. On December 31, 1856, the legislature approved the site, and it was named Burrowville (sometimes spelled Burrowsville) after Napoleon Bonaparte Burrow, a Crawford County planter and politician.

On May 16, 1857, George and Rachel Norman sold the county eleven acres for the county seat for five dollars. On July 21, 1857, John J. Dawson was named postmaster of Burrowville, which was built around a square that comprised a log courthouse, a two-story log hotel, and the McCarn & Thomas mercantile; houses were scattered around the eleven-acre town site.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The Civil War was a significant transitional event for Marshall. It changed the name of the town, retarded its growth for years, and established a vibrant two-party political system in what was for many years a one-party state. It also caused desolation—much of Burrowville/Marshall was burned, including the courthouse and county records, and many families fled to northern states or to Union-occupied Arkansas for safety. Neither Union nor Confederate forces controlled the area after mid-1863, leaving it in anarchy and subject to guerrillas of all persuasions. The Skirmish at Burrowsville in early 1864 saw fighting between the cavalries of both sides.

At the beginning of the Civil War, almost all Searcy County citizens opposed secession and Confederate military service. Searcy County did provide three Confederate companies in 1861, but many men joined under duress. On November 17, 1861, the Arkansas Confederate authorities discovered a secret pro-Union Peace Society in north-central Arkansas and tried to arrest all members. Searcy County, under Colonel Samuel Leslie of the Searcy County militia, was the center of the effort to suppress the organization. The captured Peace Society members were guarded in the courthouse. On December 9, 1861, seventy-seven prisoners were sent to Little Rock, where they were encouraged to join the Confederate army. Not all of the society’s men were arrested, however, and regular Confederate troops were stationed in Burrowville to continue the campaign against the Unionists after the Searcy County militia was discharged on December 20, 1861. On January 29, 1862, these Confederate troops were ordered to Pocahontas (Randolph County), and a Home Guard was formed to maintain order, which it did poorly, and later to enforce a conscript law, which it did too well.

Confederate soldiers whose term of service had expired or who deserted began to return in mid-1862 and hid in the woods or fled to Missouri. Some who remained in the area found that, by working with the Confederate Nitre & Mining Bureau, they avoided conscription. They mined niter for gunpowder, which was the major Confederate activity in the county until late 1863, when the mining operation moved to Texas, leaving the area in the hands of guerrillas.

In January 1864, a Union expedition from Springfield, Missouri, camped in Burrowville for two weeks and raided the area, pursuing Confederate partisans. Union forces burned the courthouse and looted the town. County government ceased to function, and Governor Isaac Murphy appointed the county officers for the next term (1864–1866).

After the war, the political situation was still so volatile that U.S. troops were stationed in Burrowville for a few months to keep peace. County Unionists pushed to change the town’s name to Marshall after U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall, and the legislature approved the change on March 18, 1867.

Civil War devastation was so pronounced that refugees returning from 1866 to 1870 from Missouri, Kansas, Illinois, and the Federal post at Lewisburg (now Morrilton in Conway County) had to rebuild from scratch. A wooden courthouse was built in about 1868, and merchants and saloonkeepers opened new businesses. A government still, gristmill, and cotton gin about a mile west of Marshall at Springtown provided a small industrial push. Eggs and other local produce were shipped out on freight wagons. Despite the mountainous terrain, cotton was the principal cash crop and was shipped through Marshall. Cattle and even flocks of turkeys were driven to market in Little Rock.

Post Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

In the early 1880s, farmers formed societies—Agricultural Wheel and the Brothers of Freedom—in the county to protect their interests. The 1884 election sent Wheeler candidate Benjamin F. Snow to the sheriff’s office for one term.

At the end of the 1880s, rail companies began exploring the area. A lead, zinc, and copper mining boom hit the county and its northern neighbors. Miners from out of state bought mining claims, and north Arkansas investors, including some from Marshall, formed mining companies. Some succeeded, and some failed, but the mining boom encouraged the building of the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad. The overcapitalized and poorly planned railroad completed a line from Seligman, Missouri, to Marshall on August 1, 1902. Marshall had already started to build homes and businesses, but the railroad allowed cheaper freight and more business. The town grew from 260 in 1900 to more than 700 in 1905. Mining and timber helped the economy and increased the population.

The Missouri & North Arkansas’s financial problems were exacerbated by a strike that temporarily closed the railroad in 1921. Its problems coincided with the expansion of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) into Searcy County. The KKK took management’s side and participated in the harassment of railroad workers and their sympathizers. The local economy faltered as the railroad failed to function effectively after the 1921 strike. The KKK’s activity produced immediate opposition that produced the anti-KKK newspaper, the Eagle, in 1923. The decline and disappearance of the KKK due to its activity and the election of anti-KKK officials in subsequent elections killed the KKK in the area and caused the eventual collapse in 1929 of the Eagle.

The 1930s Depression had a minimal impact on the rural Ozarks, but things were not quiet in Searcy County. The downward economic trend that started in 1920 continued, leaving many men without employment and too much time on their hands. A feud between two Republican families, Henley and Barnett, erupted over the 1930 sheriff’s election, and five people were killed. In the 1930s, Marshall and Searcy County took full advantage of national assistance programs, but the county continued to lose population, as it had since 1921 with the failure of a timber boom and the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad. As the good bottomland was acquired by large landowners since the 1880s, many Searcy County families left for new land in Texas, Oklahoma (Indian Territory), Idaho, and Washington. The timber industry had already been hampered by the advent of Prohibition, which did away with the market for oak barrels used to store whiskey.

World War II through the Faubus Era

World War II brought little industry to the area but took away families to work in the defense industry and young men to serve in the military. Some time after the soldiers’ return to Marshall—led by ex-Navy Seabee James R. Tudor, owner of the Marshall Mountain Wave newspaper—they sought to create jobs by founding the Searcy County Industrial Development Corporation in 1962. It attracted a shirt factory to Marshall that became the county’s principal employer. Tudor’s efforts to establish a hospital failed, but he led the effort to establish a county library in an attractive new building. With many members of the industrial development agency, he formed the Buffalo River Improvement Association, which resurrected pre–World War II Corps of Engineer plans to put dams on the Buffalo River. Canoe clubs originally led the opposition to the plan, and the dam proposals were defeated. In 1972, dam opponents’ campaign to establish the Buffalo National River was successful.

From the 1940s to 1960s, the Flintrock Strawberry Growers Association promoted their product, and strawberries became the primary cash crop until transient pickers no longer came for the picking season and local pickers no longer could handle the volume. Jack Treece, a World War II Navy pilot instructor, brought cable television to Marshall around 1950 in one of the state’s first cable TV operations. In 1968, a fire destroyed all the businesses on the north side of the square. The buildings were rebuilt, but the businesses did not return.

Modern Era

In 2004, the Marshall school system joined the Witts Springs and Leslie schools to form the Searcy County School District with two campuses—one in Marshall and one in Leslie.

The timber, dairy, tourism, and cattle industries continued to do well. In 1989, the Industrial Development Corporation backed the construction of the Searcy County Airport in Marshall, completed in 1995.

The Jim G. Ferguson Searcy County Library complements the county historical society’s annual North Arkansas Ancestor Fair, started in 1990, drawing up to 500 visitors where people swap family history stories and brag on their ancestors. Marshall has one of the state’s three surviving drive-in movie theaters, a house designed by famed architect E. Fay Jones, and turn-of-the-century stone buildings and Victorian homes.

Notable Residents

Mary Elizabeth Smith Massey was a very active and successful businesswoman and politician in the area through much of the 1900s. Well-known residents also include singer and yodeler James Britt “Cute” Baker (Elton Britt), whose 1942 “There’s a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere” sold more than four million copies. James Morris (a.k.a. Jimmy Driftwood), who wrote the Grammy Award–winning “Battle of New Orleans,” graduated from Marshall High School in 1928 and was superintendent/teacher/coach at Snowball (Searcy County) when he wrote and recorded “Battle of New Orleans” in November 1957. The Fortune 500’s Donald R. Horton, chairman of real estate and home-building company D. R. Horton Incorporated, was a Marshall resident and graduate of Marshall High School. Composer and songwriter Wilbur Carl “Skip” Redwine was born in Marshall and went on to compose music for Broadway musicals, television, advertisements, and movies.

Attractions

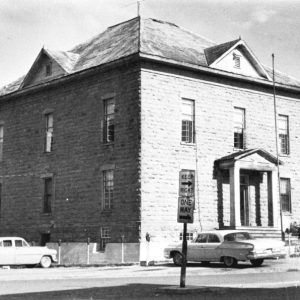

Built in 1889, the Searcy County Courthouse is one of the oldest courthouses in Arkansas and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. Kenda Drive-In theater opened for business in 1966 and was still operating by 2020.

For additional information:

Johnston, James J. Searcy County to 1850. Fayetteville, AR: Searcy County Publications, 1991.

———. Shootin’s, Obituaries, Politics: Emigratin’, Commercializin’, Socializin’, and the Press. Fayetteville, AR: Searcy County Publications, 1991.

Warren, Luther E. Yellar Rag Boys: The Arkansas Peace Society of 1861 and Other Events in Northern Arkansas, 1861 to 1865. Marshall, AR: Sandra L. Weaver, 1993.

James J. Johnston

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Buffalo River Bridge

Buffalo River Bridge  Church of the Nazarene

Church of the Nazarene  Marshall Courthouse Square

Marshall Courthouse Square  Marshall Depot as Home

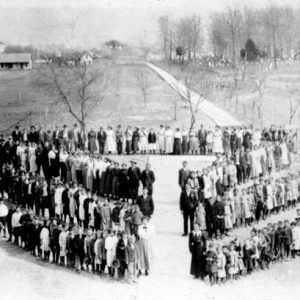

Marshall Depot as Home  Marshall School

Marshall School  Marshall Strawberry Pickers

Marshall Strawberry Pickers  Marshall Street Scene

Marshall Street Scene  Marshall Street Scene

Marshall Street Scene  Searcy County Courthouse

Searcy County Courthouse  Searcy County Courthouse

Searcy County Courthouse  Searcy County Map

Searcy County Map

In reference to the SCSD, the Witt Springs school closed July 2004, and all students were bussed to Marshall beginning the 2004/2005 school year. In 2006/2007, Leslie 9th-12th attended half days at Marshall. In 2007, Leslie 7th-12th grades were bussed to Marshall, leaving the K-6th in Leslie. In 2012, all grades K-4th attend at the Marshall campus and all 5th and 6th attend at the Leslie campus.