calsfoundation@cals.org

Jefferson County

| Region: | Central |

| County Seat: | Pine Bluff |

| Established: | November 2, 1829 |

| Parent Counties: | Arkansas, Pulaski |

| Population: | 67,260 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 872.37 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

772 |

2,566 |

5,834 |

14,971 |

15,733 |

22,386 |

40,881 |

40,972 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

52,734 |

60,330 |

64,154 |

65,101 |

76,075 |

81,373 |

85,329 |

90,718 |

85,487 |

84,278 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

77,435 |

67,260 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

25,478 |

37.9% |

| African American |

37,835 |

56.3% |

| American Indian |

240 |

0.4% |

| Asian |

673 |

1.0% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

94 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

869 |

1.3% |

| Two or More Races |

2,071 |

3.1% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

1,488 |

2.2% |

| Population Density |

77.1 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$40,726 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$21,472 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

22.2% |

|

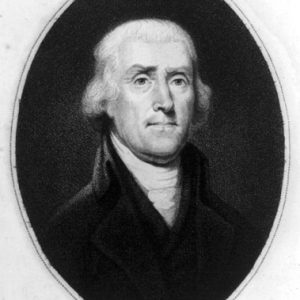

Named for former president Thomas Jefferson, Jefferson County has survived devastating floods, economic depression, and the Civil War. It is home to the Pine Bluff Arsenal and the National Center for Toxicological Research, and it was the home of Willie Mae Hocker, the designer of the official state flag. Jefferson County began as the state’s major entry point for early European explorers and steamboat travel up the Arkansas River, and a major railroad route went through it into the heart of the state. Towns that make up the county are Altheimer, Humphrey, Pine Bluff, Redfield, Sherrill, Wabbaseka, and White Hall.

European Exploration and Settlement

On June 18, 1541, Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto led the first Europeans into southeast Arkansas. Although the exact location and routes of de Soto’s Arkansas journeys are in dispute, it is known that his expedition encountered thriving villages of Native Americans numbering in the thousands in connecting settlements along the state’s southeast border. In 1673, the French, led by Father Jacques Marquette, descended the Mississippi River and entered southeastern Arkansas to claim the land. He was welcomed by the Quapaw who held a feast and celebration in his honor. The Quapaw, also identified as “Arkamsea,” or “People of the South Wind,” spoke a dialect called Dhegiha Siouan, closely related to the Osage, Omaha, Kansa, and Ponca languages. They appear to be related to the woodland peoples and probably had traveled from the Ohio River Valley to the Arkansas River Valley some time after de Soto’s expedition had left the area. Their territory once extended from the mouth of the St. Francis River northwest to the White River, north to the present-day site of Ozark (Franklin County), south to the Arkansas River, west to the Canadian River in Oklahoma, south again to the Red River, and east to Point Chicot on the Mississippi River—an area encompassing some 30 million acres.

Marquette’s expedition was followed in 1682 by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, a Frenchman from Canada with fifty-four people in tow, who boated down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. One of La Salle’s lieutenants, Henri de Tonti, an Italian by birth, returned in 1686 and built the first European settlement in the future state at Arkansas Post—a crude, wooden encampment close to the mouth of the Arkansas River and near a Quapaw settlement called Osotouy in present-day Arkansas County.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Jefferson County, like all of Arkansas, was acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. On August 24, 1818, the Quapaw ceded their lands to the U.S. government and ended up with only 1,500,000 acres in southeast Arkansas—mostly Jefferson County—on August 24, 1818. Chief Sarasin was the last and most important chief in the Jefferson County Indian territory; he is buried in the cemetery of St. Joseph’s Church in Pine Bluff. Robert Crittenden, the first territorial secretary, acquired what remained of Quapaw lands in southeast Arkansas on November 15, 1824. The Quapaw had relinquished their remaining tracts in the area in a treaty signed at Major John Harrington’s lodge on the north bank of the Arkansas River near the present location of Lock and Dam Number Three in Jefferson County. At first they were relocated to land already possessed by the Caddo in the Red River Valley. Represented by Jefferson County plantation owner Antoine Barraque, they traveled to the Red River Valley in 1826, only to return to Jefferson County shortly thereafter. Eventually, they signed a relocation treaty which placed them in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

One of the first permanent settlers of record in Jefferson County was Joseph Bonne, who brought his Quapaw family from Arkansas Post to live on a pine tree–covered bluff on the Arkansas River that would become the namesake and location of Pine Bluff. Bonne’s crude lodge became an important entry point for travelers and settlers making their way up the river. Several other families, largely of mixed French-Quapaw ancestry, lived along the Arkansas River both before and after the Louisiana Purchase, mainly with land grants issued by the Spanish government shortly before it relinquished the lands to France in 1800.

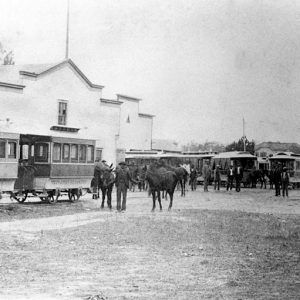

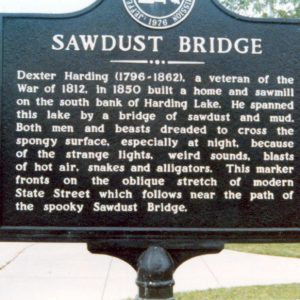

The first steamboat, the Comet, arrived at Arkansas Post in 1820. Steamboat travel on the Arkansas, which began in earnest in the late 1820s, opened southeast Arkansas for trade and commerce. Territorial governor John Pope approved an act to establish the county on November 2, 1829. The first county seat was at Bonne’s cabin. On August 13, 1832, the county seat was moved to Pine Bluff, which was surrounded by sawmills and rich farmland. Cotton farming was established early on in Jefferson County, with the Bayou Bartholomew providing easy transport for both cotton and timber. The county’s first governor/mayor in 1849 was John Selden Roane.

The first church of record in Jefferson County was Methodist, established in 1829. A small Catholic church, the first Catholic church in Arkansas, was built in January 1832 at the small hamlet called Plum Bayou.

On June 15, 1836, Arkansas became the twenty-fifth state, and Samuel C. Roane became the first state senator from Jefferson County. W. Phillips was the first representative. As steamboats plied the Arkansas River, land travel to the state capital at Little Rock (Pulaski County) became more accessible by the congressionally approved Columbia to Little Rock Military Road, which bisected Jefferson County from the southeast.

The county’s first newspaper, the Jeffersonian, was published weekly under editor W. E. Smith. Methodist and Catholic leaders instituted formal education for Jefferson County children in 1838. St. Mary’s Catholic Church established an academy to educate children, as did the Methodist Society. From 1850 through the 1860s, settlers from states east of the Mississippi poured into Jefferson County, followed by a large contingent of German Jews from Bavaria.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The economy of Jefferson County was closely tied to the institution of slavery, as large-scale, labor-intensive row crops dominated the county. The 1860 federal census recorded 7,957 white citizens in the county with 7,146 enslaved people and twelve free African Americans. This gave the county the third-highest number of enslaved people in the state, trailing only Phillips and Chicot counties.

At the 1861 Secession Convention, the county was represented by James Yell and William Grace. Yell owned or held in trust more than twenty enslaved people, while Grace owned at least three. Before Arkansas seceded, Jefferson County was the site of the seizure of supplies destined for the Federal garrison at Fort Smith (Sebastian County).

During the Civil War, Jefferson County sent two companies of voluntary militia into the war: the Jefferson Guard under the command of Captain Charles Carlton and the Southern Guard under the command of Captain Joseph W. Bocage. The Southern Guard became part of the Second Arkansas Infantry, while the Jefferson Guard became part of Josey’s Fifteenth Arkansas Infantry.

Other companies organized in the county joined the Ninth, Carroll’s Eighteenth, and Marmaduke’s Eighteenth Arkansas Infantry regiments, among others. Several camps were established in the county for the training of Confederate forces, including Camp Lee and Camp White Sulphur Springs.

When Union general Frederick Steele captured Little Rock on September 10, 1863, a delegation of Jefferson County residents petitioned Steele to send Federal troops to the county to establish martial law and end the looting and raiding of farms and homesteads by guerrilla bands taking advantage of the war. On September 14, 1863, the Fifth Kansas Battalion under the command of Colonel Powell Clayton was dispatched to Pine Bluff to restore law and order. Confederate forces under the command of General John S. Marmaduke tried to dislodge Union forces in an attack at Pine Bluff on October 25, 1863, but they failed. For the rest of the war, Jefferson County was under Union control, although numerous engagements took place almost until the very end of the war. Skirmishes fought in Jefferson County include Skirmishes at Pine Bluff on June 17, 1864, July 22, 1864, July 30, 1864, and January 9, 1865. Other locations in the county to see fighting included Richland, Bayou Meto, and near the farm of a Mrs. Voche. One of the last engagements to take place in the county was fought on March 4, 1865, near Pine Bluff.

The thousands of enslaved people in the county were freed during or immediately after the war. Fountain Brown, a Methodist minister who also owned a plantation, was prosecuted by Union authorities during the war for selling some of his former slaves back into bondage. His case and a potential pardon were discussed several times by Abraham Lincoln, but Brown it was well after the end of the war before he was freed.

After the war, the population of Jefferson County grew as formerly enslaved people and others moved to the area. Several institutions for the education of freedmen were established in the county including Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff), the Colored Industrial Institute, and the Richard Allen Institute. African Americans became an important part of the new economy of the county, with business owners such as Wiley Jones and Ferd Havis moving from bondage to becoming successful businessmen.

The county was also the site of multiple incidences of racial violence. The earliest recorded lynching in Jefferson County was in 1857 when an unnamed enslaved man allegedly killed a Dr. Guinn. A mass lynching of twenty-four African Americans reportedly took place in 1866. James Anderson lost his life in 1880 after he allegedly assaulted a white woman. John Kelly was accused of robbing and killing a white man, dying at the hands of a lynch mob alongside accused accomplice Gilbert Banks in 1892. Other reported lynchings included Lovett Davis, Judge Jones, and Bud Nelson.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

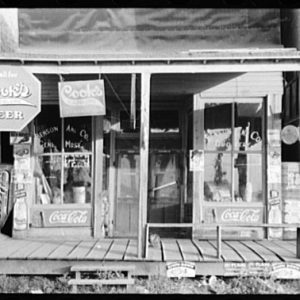

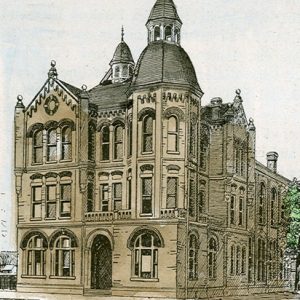

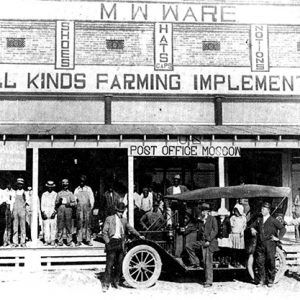

By the 1890s, Jefferson County entered what historian Jim Leslie has referred to as the Golden Era. Because of its prodigious cotton production and location near the Arkansas River, the county attracted many industries, businesses, and public institutions. Pine Bluff had become the state’s third-largest city. By the turn of the century, the county had the W. B. Ragland, Samuel Franklin, and M. L. Bell Gas Works; the Gabe Meyer public school system in Pine Bluff; the Buck, Smart & Company Bank of Jefferson County; and the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railroad. In 1881, Major C. G. Newman founded the county’s most successful daily newspaper, the Pine Bluff Commercial, which is still in operation.

Known as the “Narrow-Gauge King,” James W. Paramore in 1883 established the St. Louis Southwestern Railway (later known as the Cotton Belt Railroad), which would connect southeast Arkansas with St. Louis, Missouri. This railroad was a catalyst for the 1915 construction of the first concrete pylon, steel-supported railroad and commercial travel bridge (the Free Bridge) across the Arkansas River in southeast Jefferson County. The Cotton Belt Railroad established its main maintenance shops in Jefferson County in 1894, making it the largest employer in the county until the Pine Bluff Arsenal was built in northern Jefferson County in 1942.

Early Twentieth Century

In 1912, Wabbaseka resident Willie Mae Hocker designed the state flag as part of a contest sponsored by the Daughters of the American Revolution. Near the turn of the twentieth century, Harvey Couch moved to Pine Bluff from Columbia County, made a fortune in the emerging telephone exchange industry (later Southwestern Bell), and founded Arkansas Power and Light Company, which made him the state’s first multimillionaire and one of the state’s most influential citizens. He entertained figures such as Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt. During Hoover’s administration, Couch was the central figure on the president’s federal Reconstruction Finance Administration, established to lessen the effects of the Great Depression. He also founded the first radio station in Arkansas, WOK, which served the Pine Bluff area.

The Flood of 1927 is considered Jefferson County’s worst natural disaster, killing dozens of people and destroying tens of thousands of acres of cotton and hundreds of farmsteads and homes. With the Great Depression of the 1930s, it took the county decades to reclaim the economic status it was gaining before the flood.

Roosevelt’s New Deal programs—especially the Farm Security Administration—established farm cooperatives at Lake Dick and at Wright, where the resettlement was called the Plum Bayou Project. These cooperatives helped settle and economically sustain hundreds of Depression-ravaged, rural farm families by providing them with housing, barns, seeds for crops, farm machinery, food-producing plants, and schools. These cooperatives helped save the county and the state during the Depression. The NYA Camp Bethune for African American women also operated in the county. It provided opportunities for literacy and critical advantages to the campers.

World War II through the Modern Era

World War II brought an airfield to the county. Grider Army Airfield opened in early 1941 and trained hundreds of pilots during the war. It was turned over to the City of Pine Bluff after the war began operating as the Pine Bluff Regional Airport. A federal munitions arsenal was constructed in the county. Known as the Pine Bluff Arsenal, it employed 9,450 workers from around the county in the war years. After the war, the arsenal became a stable employer and a permanent post for the army’s production of munitions and chemical agents during the Cold War.

A June 1, 1947, tornado killed thirty-four people in the county and caused extensive damage. International Paper Company provided economic and employment stability by locating its papermaking plant in the county in 1957. At its production peak in 1962, it employed 1,400 workers. Arkansas Vocational-Technical School opened in 1959 and later began operating as Southeast Arkansas College. What is now Jefferson Regional Medical Center opened in September 1960 and employed nearly 150 medical professionals at the time. In the twenty-first century, it is Jefferson County’s second-largest employer; Tyson Foods is the top employer. The Tucker Unit of the Arkansas Department of Correction is located in the county.

Famous Residents

Well-known residents of Jefferson County include the founder of McDonell-Douglas Aerospace Corporation, James Smith McDonnell Jr. and two-time Olympic gold medalist, William Carr. Architect Fay Jones was born in Pine Bluff, as was Martha Mitchell, known for her involvement in exposing the Watergate scandal. Attorney Wiley Branton Sr. and leader of the Black Panther Party Eldridge Cleaver were also born in the county.

For additional information:

Andrus, Edward N. “The Pine, the Bluff, and the River: An Environmental History of Jefferson County, Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2011.

Bearden, Russell E. “Pine Bluff’s Golden Era: 1890–1920.” Jefferson County Arts and Science Center Publication. July 2004, p. 6.

Cunningham, Jimmy, Jr., and Donna Cunningham. African Americans in Pine Bluff and Jefferson County. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

Footprints. Pine Bluff, AR: Jefferson County Genealogical Society (1985–).

Leslie, James W. Pine Bluff and Jefferson County: A Pictorial History. Virginia Beach: The Donning Company, 1981.

———. Saracen’s Country. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1974.

Russell E. Bearden

White Hall, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.