calsfoundation@cals.org

Boone County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seat: | Harrison |

| Established: | April 9, 1869 |

| Parent Counties: | Carroll, Marion |

| Population: | 37,373 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 589.72 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

7,032 |

12,146 |

15,816 |

16,396 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

14,318 |

16,098 |

14,937 |

15,860 |

16,260 |

16,116 |

19,073 |

26,067 |

28,297 |

33,948 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

36,903 |

37,373 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

34,128 |

91.3% |

| African American |

108 |

0.3% |

| American Indian |

276 |

0.7% |

| Asian |

246 |

0.7% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

28 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

259 |

0.7% |

| Two or More Races |

2,328 |

6.2% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

973 |

2.6% |

| Population Density |

63.4 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$45,374 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$24,727 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

14.7% |

|

Located in the Ozark Mountain highlands, Boone County has endured struggles from its creation. Political, racial, and union conflicts have drawn national attention, often overshadowing the contributions of the county’s residents and businesses.

Pre-European Exploration

Archeological examinations of sites in Boone County indicate that Native American groups from a variety of time periods either lived or worked in the area. An examination of the Chaney-Crawford Site included points from the Archaic and Woodland periods, with a few from the Mississippian period. Evidence supports the idea that the site was occupied seasonally rather than permanently and served as a location to make tools.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Although they had no communities in the area, the Osage had claims to what would become Boone County until an 1808 treaty, and they often hunted there. Part of Boone County was in a Cherokee reservation which existed from 1818 to 1828. Most of the Cherokee lived further south in the reservation, away from the Osage presence to the north.

During this time, many name and boundary changes occurred. Becoming part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase, the area was part of Missouri Territory in 1812 when Louisiana was admitted as a state. When Arkansas became a territory, the area was part of Lawrence and Izard counties before Carroll County was established in 1833. The land that became Boone County had a small strip in Marion County and a much larger portion in Carroll County. The Arkansas legislature created Boone County from Carroll in 1869 and added the Marion County portion in 1875.

Native Americans, forced into Indian Territory along the Trail of Tears, crossed the land when it was part of Carroll County. A post office was established in 1836 at Crooked Creek, the town that would become Harrison. Some Arkansas residents gathered their wagons at Beller’s Stand, near Caravan Springs south of present-day Harrison, to head toward California where they intended to buy land and build new lives. However, their journey came to an abrupt end when, on September 11, 1857, a mob of Mormons ambushed the caravan at Mountain Meadows, Utah, and killed most of the people. The event is known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The Civil War hit the border region hard. The area that includes what is now Boone County had few slaves in 1860. The population of Carroll County, the parent county of Boone, included 9,053 white citizens and 330 enslaved people. The region, originally against secession, eventually joined the rest of the state in secession. Families divided: some fought for the Union, some for the Confederacy. Bushwhackers and jayhawkers (both often referred to as bushwhackers in this area) were a problem. Confederates gathered to plan and execute raids into Missouri. The Union destroyed Dubuque and its niter works, and the town never recovered. On Crooked Creek, Union forces destroyed a powder mill. Numerous skirmishes between Union forces and both Confederate and guerrilla bands took place in what became Boone County, including actions at Rolling Prairie and Sugar Loaf Prairie. Many people fled to Missouri, and the area’s population decreased.

After the war, residents petitioned the legislature to divide Carroll County. The legislature created Boone County on April 9, 1869. Land was taken from Marion County on the east and Carroll County on the west. Boone County’s northern boundary was designated part of the state line separating Arkansas from Missouri. Although no documentation supports it, the most widely quoted belief is that the county was named for frontiersman Daniel Boone. But some say the name is a misspelling of boon, because it was thought that the creation of a county would be a boon to residents. The population of the new county in 1870 included 6,958 white citizens and seventy-four African American residents.

Lines drawn during the Civil War often resurfaced in the new county. When the county seat was selected, it was not in the established town of Bellefonte but in the new town of Harrison, where Confederate beliefs were not as strong. The settlement was also named for Marcus LaRue Harrison, commander of the Union army’s First Arkansas Cavalry. Harrison surveyed the area and laid out a street grid. The Crooked Creek Post Office changed its name to Harrison in 1870. Towns began to develop. Lead Hill grew up near the site of what had been Dubuque. Smelters were built to process lead from the area. With the popularity of the healing waters in Eureka Springs in Carroll County, Boone County’s Elixir Springs was promoted.

Two noteworthy lynchings took place in the county during this time period. In 1878, a Black man named Mose Kirkendall was hanged by a mob for allegedly attempting to rape a white woman. In 1886, a white man named Andrew Mullican was taken from the jail and lynched for the murder of James Hamilton.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The post-Reconstruction era began with the resurgence of conflict between the former Confederates and the Republicans that controlled Boone County. The ex-Confederates attempted to move the county seat from Republican-controlled Harrison to Bellefonte. After a countywide vote in 1875, it remained at Harrison.

Lead and zinc mines began to appear. Fruit crops consisted of peaches, pears, plums, and the popular “Boone County apples.” Cotton was a big cash crop until declining prices cut production in half.

Early Twentieth Century

The 1900s brought change with the arrival of the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad. The railroads provided easier access to the county. Towns developed along the tracks, and existing towns grew. Alpena Pass requested a post office in 1901. Farmers grew more crops to sell because they had access to a larger number of buyers. Lumber became a big part of the economy as lumber mills and woodworking facilities appeared along the tracks. The production of cream started a new economic endeavor. When the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern Railroad set its tracks into Bergman, Boone County experienced an influx of people. By 1912, the Missouri and North Arkansas line had moved its headquarters to Harrison. The murder of Ella Barham in 1912 and ensuing trial in eastern Boone County captivated much of northwestern Arkansas, bringing notoriety to the area.

The African American population, which had shown limited growth in each census since 1870, decreased from 142 in 1900 to seven in 1910. The sudden change was attributed to race riots that occurred in Harrison, which were thought to have been caused by the arrival of workers constructing the new rail line. Another extrajudicial incident of racial violence took place in 1878 with the lynching of Mose Kirkendall. Also, the quick conviction of a young Black man for the assault of an elderly white woman brought a rapid decline in the Black population of the county. Soon, establishments providing higher wages for Black workers closed. By the time the convicted man was hanged, most Black citizens had fled the county. No Black residents were listed on the 1940 census. A non-racially based lynching took place in 1886 when Andrew Mullican was taken from the jail in Boone and lynched for the murder of James Hamilton.

World War I led to an increase in mining. Lead and zinc were needed for the war effort. Railroads allowed shipping from the region. The mining of zinc in Northern Arkansas, which included Boone County, tripled, peaking by 1917. The increase in production and the arrival of miners contributed to the county’s economy. Boone County men answered the call to fight in Europe. As in the rest of the nation, Liberty Bond rallies were held. Women knitted socks and sweaters to be sent to servicemen.

The county garnered national attention on February 18, 1921, when Henry Starr and accomplices tried to rob the Peoples National Bank in Harrison. Starr was shot by former bank president W. J. Myers and died four days later from the wound. Later that month, a strike of the Missouri and North Arkansas line occurred when workers protested reduced wages. Anger toward strike breakers resulted in threats and assaults. Trains were derailed, bridges were destroyed, and union officials were ordered out of town. Forced into receivership, the line was sold, and it reopened with lower wages. The strike continued, ending in 1923, when a mob hanged Ed Gregor on a railroad bridge and other strikers left town. More positive national attention appeared when Earl Rowland, pioneer aviator from Valley Springs, won an air race, the Ford Reliability Tour, in 1925.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Harrison was home to district headquarters for the Arkansas Highway Commission. Canning factories processed locally grown vegetables. Tourism increased as visitors hiked the Hemmed-in Hollow trail and toured Diamond Cave in neighboring Newton County. A levee was built to contain Crooked Creek, which occasionally overflowed. Bridges and roads were built, and some roads were widened. But the hard times forced many families to seek jobs outside the county.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Boone County resident Jack Williams posthumously received the Medal of Honor for courageous action at Iwo Jima during World War II. Progress followed World War II as a natural gas line was brought into Harrison and an airport was built. Duncan Parking Meter Company (today Duncan Parking Technology) moved to Boone County in 1947. They continue to produce parking meters that are used across North America. The voter-approved hospital was completed in 1950, the same year a garment factory located in the county. A food-processing plant followed. Livestock and lumber were the primary economic producers. Chalkboard maker Claridge Products and Equipment, Inc., moved to Boone County in 1955. Pace Industries, a die-casting facility, incorporated in its present location in Boone County in 1970. Turney Wood Products operated in Harrison from 1946 to 1968, producing furniture for churches using hardwood lumber.

A dam on the White River was completed in 1951, resulting in Bull Shoals reservoir and the relocation of Lead Hill and two highways. Diamond City grew at the edge of Bull Shoals Lake. After years of problems, strikes, and changes in ownership and names, the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad ceased operations in 1946.

County residents took an active part in political life. John Paul Hammerschmidt was elected Third District congressman in 1967. He served twenty-four years. J. Frank Holt served as state attorney general in 1961. After his resignation, Jack Holt Jr. completed the term; he became chief justice of Arkansas in 1985.

Modern Era

With a continually increasing population came educational and economic benefits. Voters approved the creation of North Arkansas Community College, now North Arkansas College. Tyson Foods constructed a feed mill in Bergman to handle the increase in poultry production and provide for more growers. Cavender’s Greek Seasoning located its headquarters in Harrison. The building of a regional distribution center for the U.S. Postal Service created more jobs. Dogpatch USA, an amusement park once located in nearby Newton County, helped Boone County’s tourism industry. The Boone County Regional Airport supports the tourism industry by offering commercial service to Dallas, Texas. The Buffalo River headquarters is located in Harrison and draws many tourists to the area each year, although the river itself does not enter Boone County.

The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) drew national attention to Boone County in the late 1980s and 1990s. Conflicts began when Thom Robb was elected Grand Wizard. Stories of the purchase of land for a KKK headquarters near Zinc, national meetings, and the request to adopt a one-mile section of U.S. 65 kept the county in the news. Although the KKK participated in the Adopt-A-Highway program from August 1993 to July 1997, it eventually ceased participation.

The economy still is driven by agriculture and wood products, as well as service and manufacturing. The top three employers are FedEx Freight, North Arkansas Regional Medical Center, and Pace Industries, an aluminum-die-casting company. In 2004, it ranked sixth in the state in beef cattle. The area draws many retirees. Tourism continues to play a role in the economy; travelers venture into Boone County as they head north on U.S. 65 to Branson, Missouri, or take a leisurely drive along Arkansas Scenic 7.

For additional information:

Boone County Historian. Harrison, AR: Boone County Historical and Railroad Society (2003–).

Boone County Historical and Railroad Society. History of Boone County. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Co., 1998.

———. History and Families: Boone County, Arkansas. Sikeston, MO: Acclaim Press, 2008.

Blevins, Brooks. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Froelich, Jacqueline, and David Zimmerman. “Total Eclipse: The Destruction of the African American Community of Harrison, Arkansas, in 1905 and 1909.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Summer 1999): 133–159.

Hanley, Ray, and Diane Hanley. The Postcard History Series: Carroll and Boone County, Arkansas. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 1999.

Logan, Roger V., ed. Mountain Heritage: Some Glimpses into Boone County’s Past after One Hundred Years. Harrison, AR: Harrison Junior Chamber of Commerce, 1969.

Rea, Ralph R. Boone County and Its People. Van Buren, AR: Press-Argus, 1955.

C. J. Miller

Springdale, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

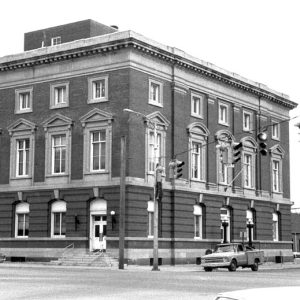

Boone County Courthouse

Boone County Courthouse  Boone County Courthouse

Boone County Courthouse  Boone County Heritage Museum

Boone County Heritage Museum  Boone County Map

Boone County Map  Harrison

Harrison  Harrison U.S. Courthouse

Harrison U.S. Courthouse  Harrison First Passenger Train

Harrison First Passenger Train  Harrison Government Building

Harrison Government Building  Harrison Town Square

Harrison Town Square  Hotel Seville

Hotel Seville  Lyric Theater

Lyric Theater  Marine Corps Legacy Museum

Marine Corps Legacy Museum  Mountain Meadows Massacre Monument

Mountain Meadows Massacre Monument  North Arkansas College

North Arkansas College  Zinc General Store

Zinc General Store

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.