calsfoundation@cals.org

Ella Barham (Murder of)

The 1912 murder of eighteen-year-old Ella Barham in Boone County was one of the most gruesome events to occur in northwestern Arkansas in the early twentieth century. The incident has intrigued people for decades, and some believe the wrong man was sent to the gallows for the crime. Much of the story has evolved into folklore.

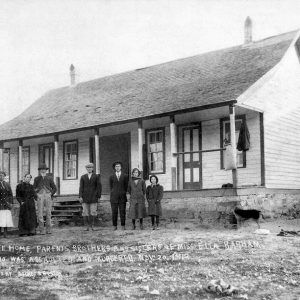

On the morning of Thursday, November 21, 1912, Ella Barham walked from her home south of Crooked Creek to the post office and store in Pleasant Ridge (Boone County), a community once located about eighteen miles east of Harrison (Boone County) near the Marion County line, to buy cloth for a hat. After returning home at about 9:00 a.m., she saddled her brother’s horse and rode to a neighbor’s house to ask for help in making the hat. The neighbor could not help, so Barham left for home after a short visit.

When Barham was not home by sundown, her mother asked her older brothers to look for her. As word of her absence spread, search parties formed. They scoured the nearby woods, the roads, and the banks of Crooked Creek. Around 9:00 p.m., two boys and a man who had earlier been hunting game found her dismembered body; her remains were scattered over a hillside south of Crooked Creek, near her home and not far from an abandoned mine shaft. Barham had been decapitated, her torso cut in two, and both legs cut off. Her clothing was strewn haphazardly on the ground. Because there were no telephones in the area, a messenger was sent to alert Boone County sheriff James Helm.

Early Friday morning, Sheriff Helm swore in extra deputies and stationed posses along the railroads. He ordered his men to watch the roads near Pleasant Ridge and to arrest any suspicious person. He tried to get bloodhounds to track the killer, but his efforts were unsuccessful.

Kansas Monroe Davidson, son of former Boone County judge James Monroe Davidson, was the justice of the peace for the Pleasant Ridge area. Acting as coroner, he rapidly formed an inquest. Doctors George Washington Taylor of Zinc (Boone County) and John Frank Lair of Pyatt (Marion County) autopsied Barham’s remains and determined that she had been raped, possibly by more than one man, and her body dismembered with a sharp-edged tool. The cause of death was a massive blow to the head; nearly every bone in her skull was crushed. The inquest paused around midday so that the Barhams could bury their daughter. When the inquest resumed, over twenty people testified, including Odus and Lair Davidson, two of Kansas’s sons.

Influenced by Ella’s father, George Solomon Barham, and the testimony of the witnesses at the inquest, but with no hard evidence or an eyewitness, the jurors suspected that Odus was guilty. A warrant was issued for his arrest.

Late Friday night, Sheriff Helm and his men rode to Davidson’s home and surrounded the house. The sheriff knocked on the door, and Kansas answered. Soon after, a hand was seen in Odus’s upstairs bedroom window dropping a pair of socks that contained red pepper flakes. (It was a common belief that red pepper would thwart a bloodhound’s sense of smell.) After his father called to him, Odus came downstairs and went peacefully with the officers to the Harrison jail. Saturday night, Lair Davidson was arrested as an accomplice and jailed alongside his brother.

Meanwhile, hundreds of people swarmed the Pleasant Ridge community, and newspaper reporters quickly spread the story from coast to coast, although many reports were inaccurate. Despite the lack of control over the crime scene, evidence mounted. Blood was found in and under a fallen treetop near the corner of the Davidson Cemetery, where it was believed Barham had been killed, and a pistol missing one bullet turned up not far away. Bloody rocks were discovered in a nearby deep ravine, along with Barham’s shoes, stockings, and hair comb. Barefoot prints led across the creek toward the location where her body was found. An axe at the Davidson’s woodpile showed traces of blood.

Threats of mob violence raged high, and the poor condition of the Harrison jail concerned Sheriff Helm, so the two Davidson brothers were secretly moved to the nearby Berryville (Carroll County) jail for their safety.

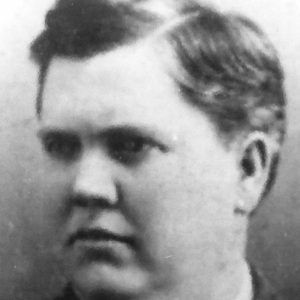

To defend his sons, Kansas Davidson hired Brice Benjamin (B. B.) Hudgins, a former circuit court judge and a Harrison community leader who had served in the Arkansas House of Representatives. Augustus Cleveland (Gus) Seawel of Yellville (Marion County) was the prosecuting attorney for the Fourteenth Judicial Circuit. Because the crime occurred within Seawel’s domain, the responsibility to prosecute the Davidson brothers was his.

The coroner’s inquest, which had not been officially completed, was taken up again on Tuesday, November 26, 1912, this time in Zinc, and under the authority of Zinc’s justice of the peace, Andrew Smith, who served as the new coroner. Many jurors were replaced due to their relationship to the Davidsons. Barham’s body was disinterred and re-examined according to Smith’s interpretation of the law.

In the Zinc schoolhouse, which was used as a makeshift courtroom, thirty people were called as witnesses, and at least twenty testified. Odus Davidson was made to press his feet into flour sprinkled on the floor so that the size of his feet could be measured against the footprints that were found at the creek. Although the footprints at the creek were larger, the demonstration proved damaging to Davidson, as some thought the prints at the creek were made larger because of the weight that the man carried—Barham’s body—as he crossed the creek.

The coroner’s verdict concluded that Odus Davidson was responsible for Barham’s death and that Lair Davidson was an accessory before the fact. When the Boone County Circuit Court convened in Harrison in January 1913, the brothers would face the grand jury and if indicted, would stand trial.

To prepare for the coming legal battle, B. B. Hudgins enlisted the help of former circuit court judge Elbridge Gerry (E. G.) Mitchell (who had also served in the Arkansas House of Representatives), attorney Albert Toney (Tony) Parrish, and Harrison attorney Oscar Hudgins, who was B. B. Hudgins’s son and law partner. Prosecuting attorney Gus Seawel was assisted by William Troy (Troy) Pace, an aggressive Harrison barrister and son of Confederate captain William Fletcher Pace, and Archibald McKennon Crump, the deputy prosecuting attorney for Boone County and son of Colonel George J. Crump, who had served the Confederacy, participated in the Brooks-Baxter War, and had been a U.S. chief marshal for the Western District of Arkansas during Judge Isaac Parker’s term on the court.

On Monday, January 13, 1913, the Boone County Circuit Court convened in Harrison, with Judge George William Reed from Heber Springs (Cleburne County), circuit court judge for the Fourteenth Judicial Circuit, presiding. Judge Reed asked John Newton Tillman—a former prosecuting attorney, former circuit court judge, and former president of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County)—to instruct the grand jurors. Thereafter, the grand jury investigated the Davidsons’ case and, on January 15, 1913, returned one indictment that jointly charged the brothers with first-degree murder and additionally charged Lair with being an accessory before the fact.

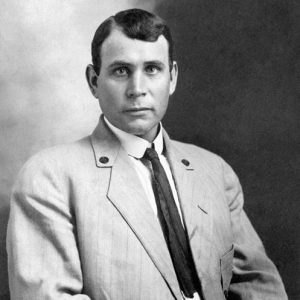

Odus Davidson’s jury trial began in Harrison on Monday, January 20, 1913. Spectators filled the courtroom, overflowed into the hallways, and spilled onto the courthouse lawn. Jury selection spanned two days, and 207 men were examined before the jury was complete. More than thirty-five witnesses testified. Davidson’s alleged motive was revealed when several witnesses stated that he had sworn he would “get even” with Barham for rejecting his advances and that he had threatened to rape her. A young woman testified that she was engaged to marry him; some thought her testimony was given to offset his alleged motive. Members of Davidson’s immediate family testified that he was at home around the time it was thought Barham was killed. He did not testify on his own behalf, and he remained stoic throughout the trial.

On Saturday, January 25, 1913, after the jurors retired to deliberate, Odus Davidson’s attorneys, fearing mob violence, made an agreement with Judge Reed to have him moved to Berryville. When the jury returned its verdict of murder in the first degree, he was not in the courtroom. Due to the late hour, Judge Reed deferred the remaining proceedings until February 3, when he sentenced Odus Davidson to hang in Harrison on March 21, 1913, in accordance with the law at that time. Lair Davidson’s trial was postponed until the July term of Boone County Circuit Court.

B. B. Hudgins, due to ill health, was unable to continue the fight for Odus Davidson’s life, but Mitchell took over. After Judge Reed denied his motion for a new trial, Mitchell appealed Davidson’s case to the Arkansas Supreme Court. One ground he cited was that Davidson’s state and U.S. constitutional rights had been violated because he was not in the courtroom when the jury rendered its verdict; thus, he had been denied due process of law. The appeal postponed his March execution, but despite Mitchell’s efforts, on June 9, 1913, the Arkansas Supreme Court affirmed the verdict of the Boone County Circuit Court. Governor Junius Marion Futrell sentenced Odus Davidson to hang in Harrison on August 11, 1913.

Mitchell made numerous attempts to appeal Davidson’s case to the U.S. Supreme Court, but his efforts failed due to timing. The court was in recess, and Willis Van Devanter, the justice in charge, did not receive all of Mitchell’s correspondence in time to evaluate the case before he left to vacation in a remote area of Canada. Mitchell petitioned Governor Futrell for a stay of execution, but his attempts were complicated by the timing of the inauguration of Governor George Washington Hays. Mitchell pleaded with Governor Hays, but Hays denied the request for a stay of execution, upon the advice of Futrell, who believed Mitchell had not exercised due diligence to get Davidson’s case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

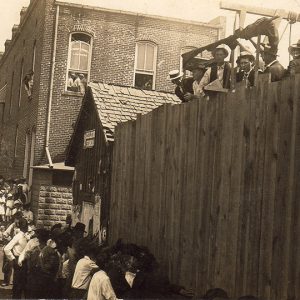

In Harrison on August 11, 1913, in the presence of a crowd that reportedly numbered in the thousands, Odus Davidson was hanged inside an enclosed scaffold. Immediately before his death, he declared his innocence to the crowd below and told them that he hoped the identity of the real killer would one day be known. The rope used to hang him was cut into pieces and tossed into the rowdy throng.

The day after the execution, Mitchell released a sworn statement that Davidson had allegedly written the day before he was hanged. In it, he asserted his innocence and forgave those whom he believed had wrongly convicted him.

Odus Davidson was the last man to be legally hanged in Boone County before the state changed its method of capital punishment to electrocution. He is buried in Harrison’s Maplewood Cemetery. His curious inscription, probably written by the flamboyant Mitchell, reads:

Here rests the ashes of

ODUS DAVIDSON

Born Jan. 22, 1883

His life taken

Aug. 11, 1913

By misrepresentations

Born of excitement.

Due to lack of sufficient evidence, the case of Lair Davidson was officially dropped in January 1914.

Kansas Davidson, his wife, and many of their children, including Lair, moved to Tahlequah, Oklahoma, in the summer of 1913, heeding a warning given by a group of armed—and some say masked—men on horseback who had visited the Davidsons’ Pleasant Ridge home in the middle of the night and threatened to destroy their home if the family did not leave the county. Ella Barham’s family remained in Boone County.

For additional information:

Case file, State v. Davidson, No. 183 (Ark. Cir. Ct. 1913). Boone County Circuit Clerk’s Office. Boone County Courthouse, Harrison, Arkansas.

Case file, Davidson v. State, 108 Ark. 158, S.W. 1103 (1913). University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law/Pulaski County Law Library, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Boone County Court Record Book L, County Clerk’s Office. Boone County Courthouse, Harrison, Arkansas.

Gould, Nita. Remembering Ella: A 1912 Murder and Mystery in the Arkansas Ozarks. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Gould, Nita, ed. The 1913 Trial of Odus Davidson: The Official Witness Testimony. Tulsa, OK: Zinc Hills Press, 2023.

Nita Gould

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.