calsfoundation@cals.org

Andrew J. Mullican (Lynching of)

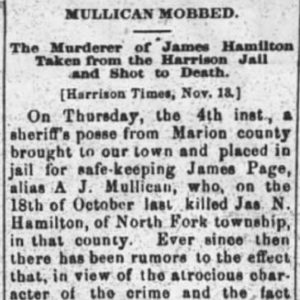

On November 11, 1886, a white man named Andrew J. Mullican (a.k.a. James Page) was shot by a mob near Harrison (Boone County) for allegedly murdering James N. Hamilton the month before.

Little is known about Andrew Mullican. He was probably the Andrew J. Malligin who in 1880, at the age of eighteen, was heading up a household in Pope County that included his sister, Sousand Malligin. Both were illiterate and working as laborers. Much more is known about his alleged victim, James N. Hamilton, who was in his thirties when he died. In 1880, twenty-six-year-old Hamilton was living in Searcy County with his wife, Nora, and their one-year-old daughter. He served for four years as a deputy collector for the United States Department of the Treasury, Office of Internal Revenue, located in Little Rock (Pulaski County). He also served as sheriff of Searcy County from 1876 to 1878. He moved to Marion County around 1885 and, in 1886, ran unsuccessfully for sheriff. The October 22, 1886, issue of the Mountain Echo of Yellville (Marion County) described him as “highly esteemed” and “a most excellent officer,” and reported that he “made a manly, open race.”

In the same issue of the Echo, a correspondent from Oakland (Marion County) reported that at 4:00 a.m. on Monday, October 18, someone had entered the bedroom where Hamilton was sleeping with his wife and child and shot him dead with his own pistol, which was hanging on the wall. Later that day, W. L. Due held an inquest, which showed that a man named James Page was the murderer. Page was arrested and awaiting trial, but a large mob took him from the guard on Tuesday morning, and though the outcome was uncertain, it was assumed that he had “met his just deserts.” A final update indicated that Page had not been lynched but had escaped from the mob and was being pursued by Deputy Sheriff Lawson.

On November 1, 1886, the Rock Island Argus identified “James Page” as Andrew Mulligan and gave a motive for his crime. Two years before, Hamilton, as Deputy Collector of Internal Revenue, had reportedly broken up some illegal stills in Johnson County. He arrested one man, but the others, including Mulligan, escaped.

The November 5 edition of the Mountain Echo also correctly identified Page, this time calling him Mullican, and reported that he had broken out of the jail at Clinton (Van Buren County) a year earlier and taken the name James Page. Page (Mullican) had been working for Hamilton since June, and James Stewart, a second hired hand, had been working for only eleven days before Hamilton’s murder. On the evening of October 17, James Hamilton and his wife went to visit neighbors, leaving Mullican and Stewart to watch the children. When the parents returned home sometime after 11:00 p.m., they found the children alone. The hired men had first gone out to shoot pistols, and then had gone to the house of neighbors named Willaby. They had supper, and at 11:00 p.m. Stewart returned to Hamilton’s house and went to bed before the Hamiltons had returned. Mullican and the Willabys went to bed at midnight, but Mullican reportedly returned to Hamilton’s home around 4:00 a.m. and killed him. He then returned to Willaby’s house, causing something of a disturbance and arousing suspicion.

After being arrested, taken from the authorities, and then fleeing the lynch mob, Mullican was again arrested on October 30. That evening he allegedly told a Mr. Holden that Stewart was angry with Hamilton after an argument about the pigpen and offered Mullican $100 to commit the crime. Mullican later reportedly confessed to being solely responsible for the murder. He gave as his motivation his infatuation with Hamilton’s wife. On November 4, Mullican, who had been jailed in Marion County, was moved to the jail in Harrison for safekeeping.

On November 19, the Mountain Echo reported in a sensational account that after Mullican was jailed in Harrison, rumors circulated that, due to the seriousness of the crime and the fact that Mullican had confessed, a mob made up of residents of Searcy and Marion counties would exact their own form of justice. On November 11, around fifty men went to the jail and forced a guard to go to the home of Deputy Sheriff J. P. Johnson and get the keys. Johnson accompanied them back to the jail, where the mob released Mullican from his shackles and took him to a hanging tree on the Bellefonte Road. Meanwhile, residents of Harrison had been roused by the ringing of bells and the shouts of the crowd, and flocked to the area. Mullican was ultimately shot and killed. Half of the mob then departed on the Marshall road to return to Searcy County, and the others left on the Yellville Road back to Marion County. A coroner’s inquest the following day determined that Mullican had died from seven pistol shots fired by unknown assailants.

A separate item in Mountain Echo that day declared that while Mullican deserved death, the lynching was an “atrocious crime,” and “there was no excuse in the world for the interference of a mob.” Local officers had Mullican in custody and were vigilantly guarding him. In due course, he would have been tried and convicted: “His public and legal execution would have had a salutary effect as an example, while his death at the hands of a mob has left a stain on the county and set a most pernicious example. The argument that by mobbing the accused murderer the county has been saved a great expense, is indeed no argument at all.”

For additional information:

“Brief Mention.” Mountain Echo (Yellville), November 19, 1886, p. 1.

“A Cold-Blooded Murder.” Rock Island Argus (Rock Island, Illinois), November 1, 1886, p. 2.

“The Hamilton Murder.” Mountain Echo (Yellville) November 5, 1886, p. 1

“James Hamilton Murdered.” Mountain Echo (Yellville), October 22, 1886, p. 1.

“Local Echoings.” Mountain Echo (Yellville) November 12, 1886, p. 2.

“Mullican Mobbed.” Mountain Echo (Yellville), November 19, 1886, p. 1.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Law

Law Transportation

Transportation Andrew Mullican Lynching Article

Andrew Mullican Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.