calsfoundation@cals.org

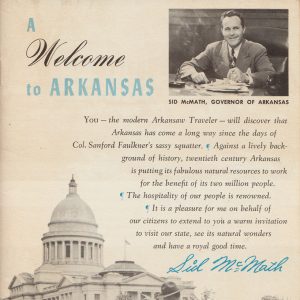

Sid McMath (1912–2003)

aka: Sidney Sanders McMath

Thirty-fourth Governor (1949–1953)

Sidney Sanders McMath—who became a prosecuting attorney, decorated U.S. Marine officer, and governor—rose to national attention by prosecuting Hot Springs (Garland County) mayor Leo McLaughlin, and he used that exposure to launch a campaign for governor. He was a close political friend to President Harry Truman and a dedicated foe to the Dixiecrat movement that tried to control the Democratic Party in the South in the 1948 presidential campaign.

Sid McMath was born on June 14, 1912, to Hal Pierce McMath and Nettie Belle Sanders McMath in Columbia County. McMath’s father inherited the family farm when his father, the county sheriff, died in a shootout with bootleggers. McMath’s father had a restless spirit and gave up the farm before McMath was five. Moving around for a few years, the family settled in Hot Springs before McMath’s tenth birthday. Over the next eight years, McMath did odd jobs, observed the “spa city” at its zenith as a haven for gangsters, and graduated from Hot Springs High School in 1931.

In high school, McMath decided he wanted to go the Naval Academy, but he failed the entrance exam and enrolled instead at Henderson State Teachers College (now Henderson State University) in Arkadelphia (Clark County). After two semesters at Henderson, McMath transferred to the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). There, he enrolled in a pre-law program, joined the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), gained campus attention as a thespian, and was student body president. He stayed in school year-round and graduated in the summer of 1936 with an LLB and a commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Marines.

After meeting requirements for his ROTC commission, he did a six-month tour of duty from August 1936 to March 1937 and then resigned from the U.S. Marine Corps, returning to Hot Springs to open a law practice. On May 28 of that year, he married Elaine Broughton, whom he had dated since high school. With the war in Europe, he returned to active service in August 1940. Assigned as an instructor in the Officer Candidate School in Quantico, Virginia, he soon was promoted to first lieutenant. In August 1941, Elaine gave birth to Sandy Sidney McMath. She died on May 28, 1942, from complications following a surgical procedure. After returning to Hot Springs for Elaine’s funeral, McMath left Sandy with McMath’s parents and returned to his U.S. Marine Corps assignment as American involvement in World War II was getting underway. He requested a transfer to a combat unit overseas but was assigned as an operations and training officer with the Third Marine Regiment at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. In a few weeks, he got his wish for overseas duty when his unit was sent to American Samoa.

In Samoa, McMath continued as an operations officer responsible for organizing training exercises in preparation for an anticipated campaign against Japanese-controlled islands in the Pacific. On February 1943, the Third Marine Regiment was assigned to secure the Solomon Islands. Beginning at Guadalcanal, the regiment used most of the year to advance on Bougainville. The assault on Bougainville began in December, and McMath got his wish for battlefield command. After surviving a surprise attack during its landing, the regiment began a drive to secure the island. Enemy resistance was broken at the Battle of Piva Forks. McMath’s role won him the Legion of Merit, the Silver Star, and promotion to lieutenant colonel.

The campaign took its toll on the regiment. More than 400 of its 3,700 troops were diagnosed with combat fatigue. McMath, too, was forced to leave the battle zone when he was ordered to receive treatment for filariasis at the naval hospital in San Diego, California. After three months in the hospital, with a brief furlough to visit family, he was assigned to marine headquarters in Washington DC in 1944 and resumed work in training and operations. On October 6, he married Sarah Anne Phillips in Washington DC. Anne was from Slate Spring, Mississippi, and the two had met through mutual friends soon after McMath began his new assignment. In December 1945, McMath was released from active duty and took reserve status with the Eighth Marine Regiment based in New Orleans, Louisiana. That same month, Anne gave birth to a son, Phillip. In January 1946, the McMaths moved to Arkansas.

Arriving in Hot Springs, McMath began to prepare for a campaign in the Democratic primary. Having grown up in the city, he was well aware of Mayor Leo McLaughlin’s control of city politics. The mayor presided over a political network that made it all but impossible to win a local election without his organization’s endorsement. But McMath filed for prosecuting attorney for the Eighth Judicial District without McLaughlin’s endorsement. He also recruited fellow veterans to seek office, and the GIs led a revolt against “machine politics” in Garland County.

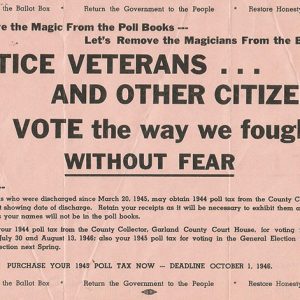

Despite a spirited campaign, all the reform candidates lost except McMath. He attributed his win to phone lines being down between Hot Springs and Mount Ida (Montgomery County), preventing McLaughlin’s group from knowing the results in Montgomery County until the next morning. Without opposition in the November general election, McMath turned to investigating why other members of the revolt were defeated. He found evidence that McLaughlin’s group was buying poll taxes, fraudulently assigning names to the tax forms, and using the tax receipts to vote in local precincts. Soon after being sworn in as prosecutor in January 1947, McMath formally charged McLaughlin with being an accessory to election fraud. The trial that followed attracted statewide attention, and even though McLaughlin was acquitted, the negative publicity was enough to force him to resign. The trial launched McMath’s political career for a statewide race. The 1948 gubernatorial race did not have an incumbent, and despite having run only one local campaign and having been in public office less than eighteen months, McMath entered the campaign.

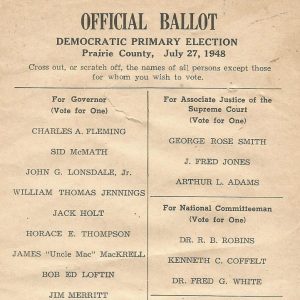

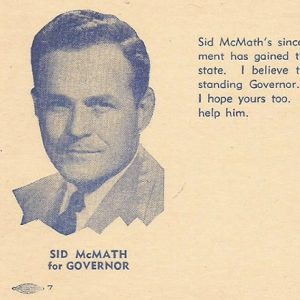

The campaign put McMath at the forefront of a postwar reform movement in the South. In a field of nine candidates, he separated himself by advocating racial moderation, support for organized labor, aid to rural Arkansas, and new highway construction. He also endorsed a school consolidation proposal that was being submitted for a vote in the November general election.

McMath won a plurality in the primary, defeated Jack Holt by 10,000 votes in the runoff, and won the general election by almost 200,000 votes. He launched his first term with a program to modernize the state. Because of bond indebtedness, the Depression, and material shortages caused by World War II, the State Department of Transportation had not authorized new road construction in more than a decade. Moreover, the existing system was in disrepair. Using money from revenue bonds authorized by voters, McMath began an aggressive building program that, in the four years he was in office, added more than 2,000 miles to the state highway system.

Keeping his promises to rural Arkansans, McMath championed a plan by the Rural Electric Administration (REA) to extend power to all regions. A key element was building a steam-generated plant to produce electricity on the Arkansas River near Ozark (Franklin County). Plans for the site had been in the making for almost a decade. But the Arkansas Power and Light Company (AP&L) opposed the construction as wasteful and unnecessary and had blocked approval in the Public Service Commission before McMath took office. He appointed a new commission, which approved the REA proposal, then used his contacts in the Truman administration to gain approval for a construction loan from the Small Business Administration. His support for the electric administration won him the permanent enmity of AP&L officials.

Education was also a priority for McMath. In addition to supporting the school consolidation movement while campaigning for governor, he appointed Alfred Bryan (A. B.) Bonds, former training director of the Atomic Energy Commission, as director of the State Department of Education and joined him in organizing an exhibit featuring the latest equipment and furniture transporting the “model classroom” to key communities. McMath also gave major support to the School of Medicine at the University of Arkansas (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) by securing funds to build a major classroom-research building and add a department of neuropsychiatry. University officials also gained his support for admitting Edith Irby Jones, the first African American student in the School of Medicine.

McMath’s role in integrating the medical school drew attention to his progressive attitude in race relations. He pushed legislators to increase funding for all-black public schools and for Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff) and provide more equitable funding for salaries of black teachers. He supported an anti-lynching bill and a proposal to abolish the poll tax but could not persuade the legislature to enact the legislation. He blocked an attempt by the segregationist Dixiecrats to take control of the Democratic Party. His support for increasing the minimum wage, advocacy for organized labor, and mediation of a ten-state railroad strike in the union’s favor added to his populist credentials.

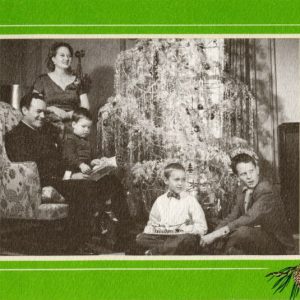

In 1948, the legislature had appropriated funds to construct a permanent residence for the governor. Construction was completed soon after McMath became governor, and his young family became the first residents of the Governor’s Mansion. By 1949, the McMath children included Sandy, Phillip, and Bruce. Twin girls, Melissa and Patricia, were born in 1953.

Success in his first term led to an easy reelection, and the programs begun in the first administration were continued. Although there was opposition to his leadership, McMath focused on his success and popularity. Early in 1951, he announced that he would seek a third term. But plans were underway in the Arkansas General Assembly to investigate complaints of fraud in the highway program. Charges were leaked to the press by road contractors who claimed they were required to make a campaign donation to McMath’s reelection fund before being awarded a contract. The investigation extended through most of his last year in office and haunted him as he campaigned for a third term. Neither he nor any of his administration was indicted in the investigation, but the perception of fraud and the weight of a third term were too great. McMath suffered a crushing defeat by Francis Cherry in the Democratic Party’s runoff primary. He twice tried a comeback, running in 1954 in a U.S. Senate race against incumbent John L. McClellan and in 1962 against Governor Orval Faubus, but never again was he elected to public office.

After his involuntary retirement from public service at age forty-one, McMath returned to law. He and his former chief of staff, Henry Woods, joined Leland Leatherman to form the state’s first “people’s law firm” to represent “workers, consumers, and victims of personal injury.” For more than forty years, he was an advocate for “blue collar” Arkansans, primarily in the area of product liability. In the summer of 1966, at age fifty-four, he returned to active duty with the U.S. Marine Corps for a two-week tour of duty in Vietnam.

Being a former governor and a highly successful trial lawyer allowed McMath many personal honors. He served as president of the International Academy of Trial Lawyers, was awarded the Grand Cross by the Thirty-third Degree Masonic Order, achieved the rank of major general in the Marine Corps Reserve, and was awarded honorary Doctor of Law degrees from Henderson State University and the University of Arkansas and an honorary Doctor of Science degree from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. McMath married artist Betty Dortch Russell in 1996.

McMath died on October 4, 2003, in Little Rock and is buried in Pinecrest Cemetery in Saline County.

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Lester, Jim. A Man for Arkansas: Sid McMath and the Southern Reform Tradition. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Co., 1976.

McMath, Sidney S. Promises Kept. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Ramsey, P. H. “A Place at the Table: Hot Springs and the GI Revolt.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Winter 2000): 407–428.

Reed, Roy. “Sidney S. McMath, 91, Former Arkansas Governor.” New York Times, October 6, 2003. Online at http://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/06/us/sidney-s-mcmath-91-former-arkansas-governor.html (accessed January 3, 2023).

Sid McMath Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at http://purl.oclc.org/arstudies/bc-mss-1833 (accessed July 6, 2023).

Sidney S. McMath Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

“A Tribute to Governor Sidney S. McMath.” UALR Law Review 26 (Spring 2004): 515–542.

Woods, James. The Era of Sid McMath, Arkansas Political Leader, 1946–1954. Little Rock: 1975.

C. Fred Williams

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Back in the 1970s, I had the good fortune to attend most of the famous medical malpractice trial of Gambill v. Stroud, where the surgical removal of a mole left the patient a vegetable for the rest of her life. Jack Deacon was the hospital’s attorney and as slick an operator as I ever saw. In later years, he spoke to my law classes. Sid McMath and Henry Woods were the attorneys for the plaintiff. At stake was the locality rule. Under it, no outside expert witness could possibly know how they practiced medicine at St. Bernard’s (the apostrophe later disappeared). It was a hard and fast medical rule that no doctor could ever testify against another; hence it could not be proved that turning patients into vegetables was normal in Jonesboro. The case was further complicated because the nurses involved all got together and lied about what had happened. That at the time was part of their canon of “ethics.” My wife Carol worked there as a unit secretary and witnessed their planning session.

Watching the two work in tandem was eye-opening. Sid was super smooth, leading the jury along a golden road; by contrast, Henry was a bulldog locked in a pen with a group of rats and piling up the victories. I also talked to the expert witness whose sole role was to show the costs of keeping the plaintiff.

At first, the state Supreme Court sustained overturning the locality rule but then reversed itself. Suspicions of corruption in this matter, and that Arkansas Medical Society bought the legislation it thought it needed, remained in my mind.

Schmidt v. Gibbs (1991), where the patient caught fire and later died, turned the corner as well as hospital advertisements promising quality care.