calsfoundation@cals.org

Freedmen's Bureau

aka: Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands

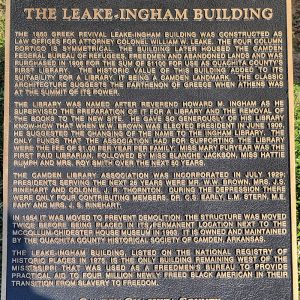

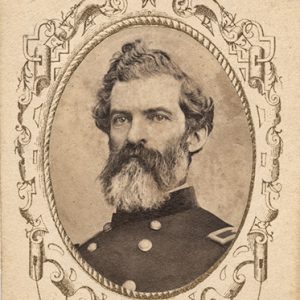

Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in March 1865 to help four million African Americans in the South make the transition from slavery to freedom and to help destitute white people with food and medical supplies in the dire days at the end of the Civil War. Headed by General Oliver Otis Howard, the Freedmen’s Bureau was supervised in Arkansas by assistant commissioners General John W. Sprague (April 1865–September 1866), General Edward O. C. Ord (October 1866–March 1867), and General Charles H. Smith (March 1867–May 1869). The bureau attempted to help Arkansas’s estimated 110,000 slaves become truly free as the Civil War ended.

Seventy-nine local agents (thirty-six civilians and forty-three army officers) labored from 1865 to 1869 in thirty-six locales to implement the bureau’s objectives. Local offices were located in areas of heavy black population where rivers and large plantations converged, primarily in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and in thirty towns south, east, and west of the capital. These locations included: Auburn (Arkansas County), South Bend (Arkansas County), Hamburg (Ashley County), Warren (Bradley County), Hampton (Calhoun County), Luna Landing (Chicot County), Lake Village (Chicot County), Arkadelphia (Clark County), Magnolia (Columbia County), Lewisburg (Conway County), Jonesboro (Craighead County), Marion (Crittenden County), Princeton (Dallas County), Napoleon (Desha County), Monticello (Drew County), Union (Fulton County), Washington (Hempstead County), Batesville (Independence County), Jacksonport (Jackson County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Clarksville (Johnson County), Lewisville (Lafayette County), Jacksonville (Pulaski County), Osceola (Mississippi County), Camden (Ouachita County), Helena (Phillips County), DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Little Rock, Evening Shade (Sharp County), Paraclifta (Sevier County), Rocky Comfort (Little River County), Madison (St. Francis County), El Dorado (Union County), Fayetteville (Washington County), Searcy (White County), Augusta (Woodruff County), and Dardanelle (Yell County). A sample of twenty-five agents reveals that thirteen were northern-born, six were southern-born, three were native Arkansans, and three had originally come from Europe. Agents’ motives and political ideals varied widely; some genuinely tried to help former slaves gain economic, social, and political freedom, while others became planter pawns and tried to reinstitute slavery and white supremacy. Agent Thomas Hunicutt, for example, required sexual favors from black women before he would give them or their families a contract.

Bureau agents supervised the Arkansas economy in the turmoil after the Civil War. Trying to negotiate fair contracts between planters and freedmen, bureau agents negotiated contracts that ranged from $5 to $60 a month for former slaves. Other agents turned to sharecropping and negotiated deals with planters that gave freedmen from one-eighth to three-fourths of the harvested crop. Bureau officers supervised working conditions and threatened to sue any planter who violated his contract with the freedmen. Some agents, realizing that former slaves needed to own their own land, encouraged them to settle on land made available by the Southern Homestead Act (1866). Over 1,000 African Americans entered claims for land during the bureau’s tenure, and 250 of these actually completed their claims and received land.

Agents often tried to protect black citizens’ civil and political rights. During elections, when groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) intimidated, abused, and killed scores of black Arkansans and burned black churches and schools, local agents monitored the situation and requested army troops when necessary. Many agents encouraged black men to register to vote in elections that dealt with new constitutions and political officials. Agents encouraged black men to support the party of Abraham Lincoln, the Republican Party.

Bureau officials tried to help reconstruct families that often had been ripped apart during slavery. Agents helped freedmen write advertisements for lost family members and provided funding for transportation that reunited many families. They paid religious and civil officials to perform wedding ceremonies that officially sanctioned such marriages, since marriages were not solemnized in churches under slavery.

Responding to the demands for schools, bureau agents funded new schools in Arkansas from monies donated by religious associations, Congress, the Arkansas legislature, and by black citizens themselves. In 1868, for example, black Arkansans contributed over one-third of the funds for building school facilities. Sixty teachers (fifty black and ten white) labored in Arkansas from 1868 to 1869 as black people used reading and math skills to appraise their contracts, calculate their debt or profit at harvest time, and vote intelligently. By the time of the bureau’s withdrawal from Arkansas in 1869, over 40,000 African Americans had obtained basic literacy and math skills in over 149 schools.

Bureau agents confronted many challenges. Two agents were murdered in Fulton and Little River counties in the line of duty, and many more were threatened with death or beatings. This physical intimidation and coercion made it difficult to fill empty bureau positions, causing many local agencies to remain unmanned throughout Reconstruction.

As Reconstruction ended in Arkansas, and as the white elite regained political and economic control of the state, the Freedmen’s Bureau ended its services in 1869. Although it was not, as African Americans had dreamed, the Day of Jubilee, it was a beginning of freedom and an end to slavery.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. “Reconstruction in the Ozarks: Simpson Mason, William Monks, and the War That Refused to End.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Autumn 2018): 175–207.

DeBlack, Thomas. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1865–1869. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

———.“The Personnel of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas.” In The Freedmen’s Bureau and Reconstruction: Reconsiderations, edited by Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999.

Freedmen’s Bureau Online. http://freedmensbureau.com/arkansas/index.htm (accessed August 26, 2023).

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction in Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Randy Finley

Georgia Perimeter College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.