calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil Rights & Social Change

aka: Arkansas's Free Negro Expulsion Act of 1859

aka: HB 1570

aka: Arkansas ACLU

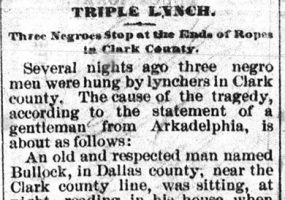

aka: James X. Caruthers and Bubbles Clayton (Trial and Execution of)

aka: Arkansas Association of Women’s Clubs, Inc.

aka: Arkansas Association of Women, Youth, and Young Adults Clubs, Inc.