calsfoundation@cals.org

Tucker Unit

aka: Tucker Prison Farm

Tucker Unit, often referred to simply as Tucker or Tucker prison farm, is a 4,500-acre maximum security prison and working farm located in Tucker (Jefferson County), roughly twenty-five miles northeast of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). It is one of thirteen prison units in the Arkansas Department of Correction. Tucker Unit is not to be confused with the Maximum Security Unit, which was built in 1983 and is also located in Tucker. Tucker is the second-oldest prison in Arkansas (Cummins Unit is the oldest). Tucker was accredited by the American Correctional Association in 1983, but for many years, the prison had a tarnished reputation and was at the center of the prison scandals of the 1960s and subsequent reform efforts of Governor Winthrop Rockefeller’s administration.

Tucker was built in 1916 as the second of Arkansas’s prison farms, which replaced the inhumane and decentralized convict lease system. In 1921, however, conditions were bad enough at Tucker to spur prison board member Laura Conner to demand the removal of Tucker’s warden. Such protests were in vain.

In 1933, Arkansas closed down “The Walls” in Little Rock (Pulaski County), which had served as a waystation for sending convicts south to Tucker or Cummins. Soon after, the state’s facilities for execution, which included “Old Sparky” the electric chair, were moved to Tucker. Tucker housed death row inmates until 1974, when they were moved to Cummins. The last execution at Tucker was performed in 1964.

In the mid-twentieth century, the prison farms reflected the Jim Crow system of racial segregation: Cummins was originally intended to serve as the primary prison for African Americans, Tucker for whites. Tucker housed only whites until the 1970s. Tucker, furthermore, always had a much smaller prison population than Cummins. At the height of the prison scandals in 1968, Cummins numbered 1,219 inmates to Tucker’s 274. The age range at the prisons also differed. (Even into the 1970s, Arkansas had no legal age limit for prisoners.) Traditionally, inmates at Tucker were younger, with most of them under the age of thirty.

In terms of daily operations, Cummins and Tucker were similar. Both were created as working prison farms, modeled on antebellum plantations. Men undertook various jobs. The unluckiest labored on the “long line,” picking cotton, cucumbers, and rice. Tucker’s inmates worked hard and for no compensation. Until the 1970s, Arkansas’s prisons were expected to be economically self supporting. Crops were sold at market, though it is uncertain how much of that money was put back into the prisons on a consistent basis. Tucker did not always generate enough money to cover its operating expenses.

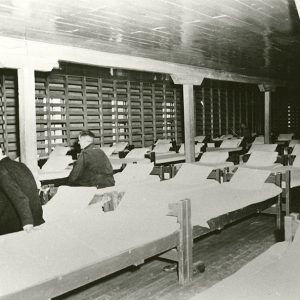

For most of its history, Tucker’s guards were “trusties,” inmates who were in charge of maintaining daily operations and enforcing discipline. At Tucker, a hierarchy developed with rank men at the bottom, do-pops (pronounced “doh pops”) above them, and trusties at the highest rungs of prison society. Trusties or “bosses” who supervised work in the fields were called long line riders; they rode horseback and had guns and clubs. Most of the men at Tucker were housed in military-style barracks rather than cells, which resulted in frequent acts of theft, violence, rape, and intimidation. Trusties considered themselves untouchable within prison walls: they beat lower-ranking prisoners for small infractions, extorted inmates, and engaged in rape and murder. Little of what happened at Tucker was known to the outside world, and few Arkansas politicians cared so long as the prisons generated sufficient funds.

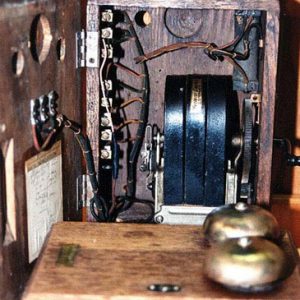

In 1966, Governor Orval Faubus commissioned a report on conditions at Tucker. The report, completed by the Arkansas State Police, was not released until early 1967, after Winthrop Rockefeller took office as Arkansas’s governor. The report, which told of systemic corruption and brutality at Tucker, shocked the new governor. The most horrifying story involved the use of the “Tucker Telephone,” an old-fashioned crank telephone used to torture inmates. When the police raided Tucker, the infamous phone was found in a shoebox in the closet of Tucker superintendent Jim Bruton. Bruton was eventually convicted in 1970 of violating prisoners’ civil rights, but he never served time. The judge suspended his sentence because he felt putting Bruton in prison would result in a virtual execution at the hands of vengeful inmates.

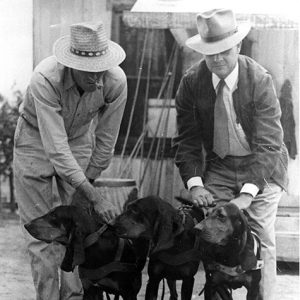

Shortly after taking office, Rockefeller hired California penologist Tom Murton to serve as the new superintendent of Tucker. Murton found conditions at the prison appalling, but over the course of the year, he improved sanitation, enforced the already existing legal ban on the rawhide lash, and cracked down on the worst abuses of the trusty system (which he did not have the legal authority to dismantle). In January 1968, Murton was transferred to Cummins, where he soon ran into trouble with the governor.

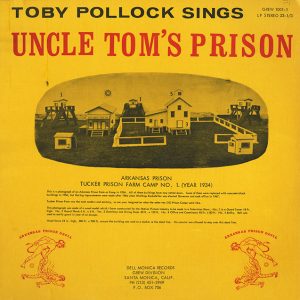

In Rockefeller’s second term, the prisons continued to generate bad publicity. In 1969, Murton published Accomplices to the Crime, which painted a graphic and repellant picture of life at Tucker. The next year, musician Elmer Mikel published Uncle Tom’s Prison about his experiences at Tucker in the 1930s. Even more importantly, in 1970, Judge J. Smith Henley ruled in the second of two cases known as Holt v. Sarver that the entire Arkansas prison system was unconstitutional, given its violation of the Eighth Amendment.

Rockefeller made significant improvements at Tucker, including the racial integration of living quarters and the dismantling, though not entirely, of the trusty system. In December 1969, Tucker was the first prison in Arkansas to have an inmate chapel, funded in part by musician Johnny Cash and Governor Rockefeller, both of whom donated $5,000 for the project.

In the 1970s, Tucker moved toward compliance with federal law and national standards. In 1983, the prison was accredited by the American Correctional Association. Some critics have noted that the modernization of Arkansas’s prisons has come at great financial and social cost. In the 1980s and 1990s, Arkansas saw a vast expansion of the prison industrial complex. The state has one of the nation’s highest incarceration rates per capita. Tucker’s notorious reputation has improved somewhat since the 1960s and 1970s. The prison is also much larger in the twenty-first century. In January 2017, Tucker had 201 employees and the capacity to house 1,126 prisoners, far greater numbers than in the days of Gov. Rockefeller.

For additional information:

Crosley, Clyde. Unfolding Misconceptions: The Arkansas State Penitentiary, 1836–1986. Arlington, TX: Liberal Arts Press, 1986.

Laura Cornelius Conner Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Mikel, Elmer. Uncle Tom’s Prison. Santa Monica, CA: E. Mikel, 1970.

Murton, Tom, and Joe Hyams. Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal. New York: Grove Press, 1969.

Urwin, Cathy. Agenda for Reform: Winthrop Rockefeller as Governor of Arkansas, 1967–71. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Winthrop Rockefeller Collection. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Colin Edward Woodward

Lee Family Digital Archive, Stratford Hall

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.