calsfoundation@cals.org

Sanitation

The term “sanitation” is used today to describe the elimination or control of dangerous bacteria, especially in drinking water and food supplies and through personal hygiene. Prior to the development of the germ theory and the subsequent discoveries in bacteriology and microbiology, the term covered all elements of health and well-being.

Sanitation, in the sense of the elimination of dangerous bacteria, is common to animals, which instinctively try to keep their feces and urine at a distance from their habitations. When humans abandoned nomadic patterns and resided in settled communities, more complicated arrangements had to be worked out. Examples practiced in the absence of scientific proof included the use of latrines, attempts to protect the purity of water supplies, and the kosher rules of the Jews. However, prior to 1880, sanitation practices in Arkansas were limited. Hogs scrounged the streets for humans’ garbage. The Town Branch of Little Rock (Pulaski County), for example, was both a dump and an open sewer. In nineteenth-century Helena (Phillips County), water from the graveyards above the town leaked into broken cisterns.

One conspicuous example of the earlier meaning of the term “sanitation” was the U.S. Sanitary Commission that was chartered by the federal government during the Civil War. The Western Sanitary Commission was created in St. Louis, Missouri, on September 5, 1861, through the efforts of Dorothea Lynde Dix, the superintendent of Union Army Nurses. The first emergency dealt with the wounded Union soldiers from the Battle of Wilson’s Creek who had been brought back by wagon to Rolla, Missouri, and then by train to St. Louis. The commission supplied soldiers and refugees with food, small personal items, and medical care. It also promoted drainage, supplied housing, and organized social welfare events. Many of the supplies—notably mittens, underwear, socks, and food—were donated, but sanitary fairs raised large amounts of money.

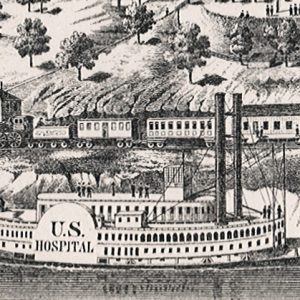

Soldiers’ homes were established to house wounded, discharged, or in-transit soldiers. On February 11, 1864, the commission opened the Helena Soldiers’ Home in Helena. Working closely with military physicians, the commission also had eight hospital steamers. Sanitary officials accompanied the Union armies into Arkansas to help provide comforts for Union soldiers. After the war, the Freedmen’s Bureau was a natural outgrowth of the Sanitary Commission’s work. In addition, women were singularly important in every aspect of commission activities.

Judged even by nineteenth-century standards, personal hygiene was often conspicuous for its absence. From as early as the eighteenth century, the prevalence of poor health virtually defined the South and its peoples. Among the almost exclusively Southern ailments were malaria, pellagra, and hookworm. According to historian George B. Tindall, these made up the “Southern trilogy of ‘lazy diseases.’” A key by-product was that those such afflicted failed to practice even minimal personal sanitary practices.

A common cause of death among women was puerperal fever—a form of septicemia that can be contracted by women during and after childbirth—that doctors and midwives with unwashed hands spread to their patients. Deaths from diarrhea were numerous and could invariably be traced to contaminated food and water. Cholera, a water-borne and almost always fatal disease, hit Arkansas repeatedly before and after the Civil War. The most common protective measure was the quarantine, enacted on an extensive scale during the outbreaks in the 1870s and used against individuals when cases of smallpox and other feared diseases appeared.

As late as 1879, efforts to control yellow fever, the causes of which were then unknown, were organized by the Little Rock Board of Health and the Sanitary Council of the Mississippi Valley. Medical personnel were sharply divided between the contagionists, who believed that the disease was spread by personal contacts, and the sanitarians, who believed that environmental conditions were to blame. (Mosquitoes were finally identified as the carrier of yellow fever.) By 1900, research into the causes of disease and the treatment of personal diseases belonged to the medical world, while the prevention of many contagious conditions fell into the realm of public health departments and organizations, which had the power to regulate. As a result of public efforts, the last major yellow fever outbreak in the United States came in 1905, but because of a quarantine that prevented travelers from south of Arkansas from entering the state, there were no reported cases in Arkansas.

The state government had only begun to act during the yellow fever outbreak. A state board of health briefly existed in 1878, and the 1879 report of the then-existing state board of health called attention to issues that would concern sanitarians even in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Dr. Charles Edward Nash labeled food as “perhaps the principal cause of ill health,” citing “putrescent” meat; overripe vegetables; “decomposing fish”; milk adulterated by chalk, sugar, and water, as well as coming from “diseased cows”; and adulterated butter. Action on these fronts, however, came first at the local level. In 1894, public alarm about an outbreak of “lump jaw” or “lumpy jaw” in cattle (actinomycosis) prompted Little Rock’s sanitary officer, Peter Schmuck, to file charges against butcher Lee Frank. The state’s case, however, collapsed in the absence of scientific evidence. Defense witness Fred Martin suggested that the steer probably just had a toothache.

In Arkansas, the first state medical board lapsed but was reactivated in the wake of the smallpox outbreak in 1897. In 1911, the first attempt at getting major progressive legislation collapsed when the bill was weakened by legislators being lobbied by the National League for Medical Freedom, the political action arm of the powerful patent medicine industry. Finally, in 1913, Arkansas got a permanent board with Dr. Charles Willis Garrison as the Arkansas state health officer. His wife, Vinnie Middleton Garrison, assisted him by helping mobilize the Arkansas Federation of Women’s Clubs in support of public health measures.

Sanitation was the foremost issue of the day because of the work of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission in identifying hookworm as a major medical problem that required both medical treatment and prevention. The hookworm campaign focused on building sanitary outhouses both in town and in the country. Rural opposition, especially by males, was strong, but, between 1935 and 1941, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) built 51,418 privies. The Arkansas Department of Education (ADE) attempted to get privies required for schools, providing simple plans and setting formulae on how many seats for males and females were needed.

The Rockefeller Foundation also launched an attack on malaria, with prevention rather than treatment as its goal. In 1919, following the passage of the Hotel Inspection Act of 1917, M. “Zack” Bair became the first sanitary engineer as the state board began inspecting water and sewer systems as well as hotels and restaurants. Instead of taste and smell of water, exact scientific measurements formed the basis for public regulation. As a result, twentieth-century Paragould (Greene County) residents learned exactly how polluted the city water was that came from the well near the country club.

The Arkansas Board of Health and the U.S. military faced a major crisis with the outbreak of influenza in September 1918. The federal U.S. Public Health Service officer in Arkansas, Dr. J. C. Geiger, minimized the significance of the outbreak while the State Board of Health was trying to implement its typhoid inoculation program in the schools over the opposition of Madison County. As the disease spread in the fall, Geiger insisted that there was nothing alarming, and the state board called merely for voluntary quarantining. Geiger did come out with a memorable poem: “Cover up each cough and sneeze / If you don’t, you’ll spread disease.” As conditions worsened, the board quarantined the whole state on October 8, 1918, although enforcement was sporadic at best. The Arkansas State Tuberculosis Sanatorium at Booneville (Logan County) quarantined itself completely and escaped without a single case of the sickness. The military was responsible for looking after the soldiers, and Camp Pike recorded more than 14,000 cases and 184 fatalities.

On October 25, the state board began relaxing the rules, allowing church services for adults for the first time since the start of the quarantine. Massive disregard of the rules came on November 11 when Armistice Day celebrations erupted, only to be followed by new waves of sickness. While the disease gradually dissipated, the only reform enacted was giving the governor the power to declare quarantine.

Federal support for public health continued in the 1920s when, under the Sheppard-Towner Act, Arkansas was able to set up the Bureau of Child Hygiene under the nationally recognized Dr. Frances Sage Bradley. Much of her work with midwives, parents, and teachers involved instruction in basic hygiene. The Flood of 1927 created sanitary emergencies, as did the Drought of 1930–1931 and the Flood of 1937, marked by outbreaks of meningitis, smallpox, and other communicable diseases. During World War II, many men and women were exposed to national sanitation practices for the first time. The military found it necessary to teach women how properly to wipe themselves. Sex education, notably the use of condoms, became important.

During the 1940s, “shade-tree” (non-professional) canning factories became a major sanitary concern. Within the Arkansas Department of Health (ADH), the Division of Food and Drug Control, established in 1946, turned its attention to the more than 250 canning plants, of which more than seventy percent used unsanitary water supplies and generally lacked sanitary provisions for their workers. By selling only in-state, some factories avoided federal inspections, but more than 100 operators were charged with shipping adulterated products in interstate commerce. New postwar rules—including screening, proper drainage, and the use of stainless steel—caused many shade-tree operations to disband, leaving only 164 canning plants. The inadequately financed program (the division had only one chemist) relied on education rather than enforcement. However, a worm infestation in the state’s spinach crop in 1950 virtually wiped out the state’s production and resulted in federal seizures and a state quarantine on all shipments. Sanitarians also were involved as rural electrification led to growth in the dairy industry. Milk inspection changed to reflect the new conditions, measuring butter fat, milk solids, and bacterial counts.

Public drinking water regulation also began after World War II. The state’s high standards, largely due to Glen Kellogg, who was employed by the state Board of Health from 1947 to 1980, were greatly in advance of other states and protected residents from some medical problems associated with unfiltered iron and manganese. Mandatory water operator licensing went into effect in 1954. Buffer zones around local water sources followed. However, by 1973, although eighty-three percent of state residents had access to safe water, only fifty-four percent had access to proper sewer systems.

Rural electrification resulted in farm families slowly abandoning outhouses in favor of indoor toilet facilities, which employed septic tanks. Many hamlets and even small towns also made use of these devices, and, as urban sprawl arose after 1970, many subdivisions outside city limits used septic tanks. Finally, vacation and retirement homes surrounding the state’s lakes added to the growing sewage problem. For example, some 4,000 malfunctioning septic tanks spilled sewage into Beaver Lake. Efforts at regulation were politically unpopular, but the bubbling up of excrement into ditches and yards created a major health concern in eastern Arkansas, and the health department was receiving some 10,000 complaints a year by 1976. Act 402 of 1977 established statewide septic standards. In an effort toward enforcement of standards, University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) professor E. Moye Rutledge was largely responsible for teaching the soil genesis and septic systems classes necessary for Professional Registered Soil Classifiers.

Despite statewide standards, controversies remained. In 2009, some forty-five miles of the Buffalo National River starting at Pruitt (Newton County) were contaminated with fecal coliform and bacteria coming from the Mable Falls Sewer Improvement District. In 2010, the state attorney general, Dustin McDaniel, filed suit against the district.

While the water and sewer issues involved a high degree of scientific expertise, routine restaurant inspections focused on the standards of cleanliness. Some newspapers published their reports, but these sanitation reports did not cover the health of workers, and, in 1994, more than sixty-five people were infected with Hepatitis A from a West Helena (Phillips County) Taco Bell, probably from one of its employees. As of 2010, restaurant inspection reports still do not cover the health of workers.

Most sanitary inspections have been done by county sanitarians, but increasingly specialized programs have led to an increase of staff in Little Rock. Covered areas include medical waste, tattoo parlors, cemetery sites, marine septic systems, and public beaches.

Personal sanitation standards seemed to have declined after 1970. Head lice, once almost extinct, reappeared in schools; sexually transmitted diseases became rampant; and home food preparation standards declined. However, the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 placed increased emphasis on hand sanitizers and other personal preventive measures.

For additional information:

Bloom, Khaled J. The Mississippi Valley’s Great Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Crosby, Molly C. The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic That Shaped Our History. New York: Berkley Books, 2006.

Griffee, Carol. History of the Little Rock Wastewater Utility. Little Rock: Little Rock Wastewater Utility, 1994.

Humphreys, Margaret. Yellow Fever and the South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992

Jones, Creo. Memoirs of an Ozark Hill Boy. Mount Ida, AR: n.d.

Rousey, Dennis. “Yellow Fever and Black Policemen in Memphis: A Post-Reconstruction Anomaly.” Journal of Southern History 51 (August 1985): 357–374.

Savitt, Todd L., and James Harvey Young. Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

Scholle, Sarah Hudson. A History of Public Health in Arkansas: The Pain in Prevention. Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Health, 1980.

Scott, Kim Allen. “Plague on the Homefront: Arkansas and the Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Winter 1988): 311–344.

United States Sanitary Commission, Western Department. The Western Sanitary Commission; A Sketch of its Origin, History, Labors for the Sick and Wounded of the Western Armies, and Aid Given to Freedmen and Union Refugees, with Incidents of Hospital Life. St. Louis: R. P. Studley & Co., 1864.

Worthen, William B. “Municipal Improvement in Little Rock—A Case History.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Winter 1987): 317–347.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Hospital Steamer

Hospital Steamer  John D. Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John D. Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.