calsfoundation@cals.org

Texarkana (Miller County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33º26’30″N 094º02’15″W |

| Elevation: | 336 feet |

| Area: | 41.98 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 29,387 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | August 10, 1880 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1,390 |

3,528 |

4,914 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

5,655 |

8,257 |

10,764 |

11,821 |

15,875 |

19,788 |

21,682 |

21,459 |

22,631 |

26,448 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

29,919 |

29,387 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

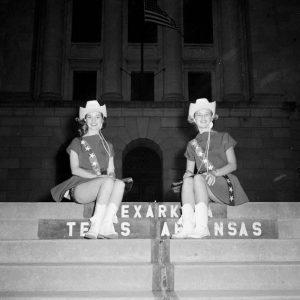

Texarkana is in the southwest corner of Arkansas at the junction of Interstate 30 and U.S. 59, 67, 71, and 82. Its two separate municipalities—Texarkana, Arkansas, and Texarkana, Texas—sometimes function as one city. The name is a composite of Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana (though Louisiana is thirty miles away). Texarkana is the Miller County seat, and is home to the only Federal Building and post office situated in two states. The city’s motto is “Twice as Nice.”

Pre-European Exploration

The area around Texarkana was inhabited at least 12,000 years ago. Several villages stood near the Red River, both upstream and downstream from contemporary Texarkana. The Red River Caddo were one of several regional Caddo groups (a Mississippian culture) who farmed the area and established permanent households roughly 1,000 years ago; the last of their settlements, Cadohadacho village, was abandoned around the year 1778. Residents of Texarkana today speak of an Indian hunting trail which connected the villages and was the basis for what came to be known as the National Road, Military Road, or Southwest Trail, roughly parallel to contemporary Interstate 30 and U.S. 67; no documents or maps verify the existence of such an Indian trail.

European Exploration and Settlement

The Caddo first encountered Europeans late in the seventeenth century. They were hospitable to Frenchmen who survived the La Salle expedition in 1687. Spaniards entered the area in 1691; shortly after that, the missionaries and small groups of Spaniards scattered through east Texas were influenced to retreat, and mission attempts were abandoned. By 1719, Jean Benard de la Harpe had established a fort and trading post called Le Poste de la Cadodaquious northwest of Texarkana.

Louisiana Purchase through Reconstruction

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Caddo had left the area, first living in Louisiana and later in Texas and Oklahoma. By 1840, enough white men had arrived in the area to form a permanent settlement, complete with a post office they called Rondo, about fifteen miles from present-day Texarkana. The location of the future Texarkana did not go unnoticed by nineteenth-century railroad men.

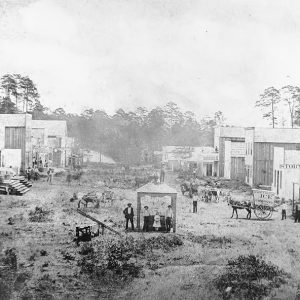

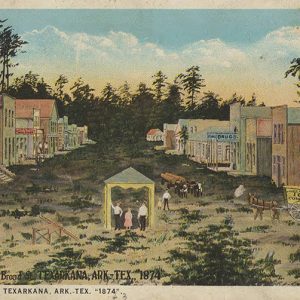

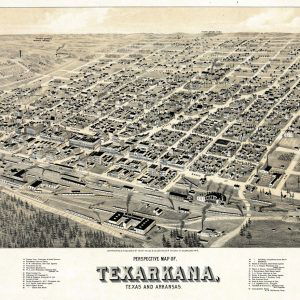

In the late 1850s, the builders of the Cairo and Fulton Railroad laid tracks in Arkansas, completing the railway to the Texas border in 1873. At the place where they would meet the Texas and Pacific Railroad (running east/west), a town site was established on December 8, 1873, with the sale of town lots. The first lot was sold to J. W. Davis and today is the site of the Hotel McCartney across from Union Station. Another sale of a town lot that day led to the opening of the town’s first business, a grocery and drugstore operated by George M. Clark.

There is evidence that the city’s name existed before the city. Some say that as early as 1860, it was used by the steamboat Texarkana, which traveled the Red River. Others say a supposedly medicinal drink called “Texarkana Bitters” was sold in 1869 by a man named Swindle who ran a general store in Bossier Parish, Louisiana. The most popular version credits a railroad surveyor, Colonel Gus Knobel, who was surveying the right of way from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to southwestern Arkansas for the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern Railroad in the late 1860s. Knobel later became chief engineer for the Texarkana and Northern Railroad. When Knobel came to the state line between Arkansas and Texas, and believing he was also at or near the Louisiana border, he reportedly wrote the words “TEX-ARK-ANA” on a board and nailed it to a tree with the statement, “This is the name of a town which is to be built here.”

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

On December 8, 1873, a group met on the Texas side to organize the city. Texarkana, Texas, was granted a charter on June 12, 1874. In 1880, twenty-one citizens met and petitioned to incorporate Texarkana, Arkansas. Public sentiment was divided, as an opposing group gathered fifteen names of citizens who opposed organizing a government on the Arkansas side. But Texarkana, Arkansas, was granted a charter on August 10, 1880, by County Judge H. W. Edwards. On November 12, the city government was established, and H. W. Beidler was elected mayor. That same year, a race riot occurred in Texarkana, sparked by a land dispute.

In 1883, Southwestern Telephone and Telegraph Exchange received a franchise for Texarkana to operate a telephone service. Throughout the 1880s, schools and churches were established in Texarkana, including a school for African Americans on the Texas side that was established in 1885, the same year ragtime legend Scott Joplin left Texarkana to pursue a career in music.

In 1890, the city’s Arkansas population (3,528) was greater than the population of the Texas side (2,852). In 1893, the first Miller County courthouse was built. It was demolished in 1939 to make way for the current courthouse. In 1894, land was purchased for the first public school on the Arkansas side.

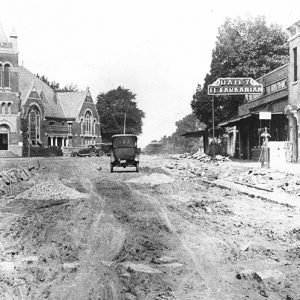

Texarkana’s post office stood on the Arkansas side until residents of the Texas side requested one of their own. A post office known as “Texarkana, Texas,” operated from 1886 to 1892; after it closed, postmarks then read, “Texarkana, Arkansas.” A compromise was reached with “Texarkana, Arkansas–Texas,” which prevailed until the adoption of “Texarkana, U.S.A.” Both cities grew throughout the 1890s, installing streetcar lines, gas works, an electric light plant, an ice factory, and sewer lines, often in as cooperative a manner as possible considering that the municipalities were in separate states. At the time, four newspapers served Texarkana.

In 1892, an African-American man named Edward Coy was burned at the stake for allegedly assaulting a white woman. In 1898, an African-American man named Bud Hayden was hanged and shot in response to allegations of a similar crime.

Early Twentieth Century through the Modern Era

In 1906, an African-American man named Anthony Davis was lynched for the alleged crime of assaulting a teenaged girl. In 1922, an African-American man named Hurley Owen was lynched for the alleged crime of murdering a police

officer.

In the early twentieth century, the population of the Texas side outpaced that of the Arkansas side, though both parts of the city grew and prospered until the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Texarkana Baptist Orphanage was established in 1908 and continues to operate in the present day. The first flight out of Texarkana Regional Airport took off in 1931 and it also continues to function in the twenty-first century.

The city’s economy rebounded with the coming of World War II in the 1940s, primarily because of the creation of the Red River Army Depot and the Lone Star Ammunition Plant. Along with being an important junction of railroad lines, Texarkana built a strong economy based on timber and minerals including rockwool (an inorganic substance used for insulation and filtering), sand, and gravel, along with agricultural crops such as corn, cotton, pecans, rice, and soybeans.

Texarkana attained notoriety with a series of grisly murders in which five people were killed and several injured between February 23 and May 4, 1946. Newspapers dubbed them the “Texarkana Moonlight Murders.” The victims were couples parked on back roads and lovers’ lanes around town. The only description of the killer was that he wore a plain pillowcase over his head, with eyeholes cut out. The case was never solved, and the killing spree ended as suddenly as it began. Three decades after the crime, the murders inspired a movie, The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1977), directed by Charles B. Pierce of Hampton (Calhoun County).

By 1952, the population was 40,490, with the Arkansas side reporting almost 16,000. By 1960, the Arkansas side had reached almost 20,000 and the total population of the city was just over 50,000.

Also in 1977, Texarkana enjoyed another measure of fame in popular culture through the hit movie, Smokey and the Bandit. The film starred Burt Reynolds, who had previous Arkansas connections by filming White Lightning in the state in 1973. He later starred in the television series, Evening Shade, about the eponymous Arkansas town. Smokey and the Bandit centers on truck drivers who transport an illegal shipment of beer from Texarkana to Atlanta, Georgia.

Economy

A significant factor in the region’s economic growth was the establishment of a low-security Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) on the Texas side near the Arkansas border. Next to the FCI is a minimum-security federal prison camp. Both facilities house male offenders, with the FCI housing more than 1,400 inmates and the camp 300 to 400.

The area has several prisons, detention centers, and penal centers, including the Miller County Correctional Facility and the Southwest Arkansas Community Punishment Center.

For commercial purposes, Texarkana is generally considered one city. State Line Avenue, the main street, was laid out to lie on the dividing line between the two states. Each side has a mayor, and there are two city councils and city staffs. There is joint operation of water facilities and the justice center, though each half of the city maintains its own police and fire departments, parks department, and sanitation department. The city has one chamber of commerce. Texas does not assess a state income tax, so residents of Texarkana, Arkansas, are exempt from Arkansas income tax, though they must file a return and claim the exemption. Differences in sales tax between the two states, including an annual Texas sales tax “holiday” in August, are often felt by local residents to be offset by the cost of gasoline in driving from one side to the other.

Agriculture, including poultry and livestock, continues to play a significant role in the city’s economy. There has also been an increase in retail, manufacturing, and industrial development along with the city’s role as a transportation hub. But recreation and tourism have also become major factors in economic growth.

Attractions

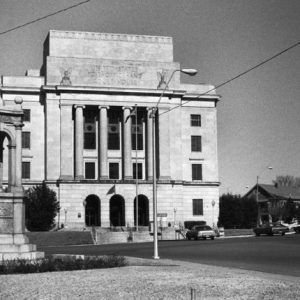

The State Line Post Office and Federal Building at 500 State Line Avenue is the only U.S. post office situated in two states, and Texarkana boasts that it is the most photographed courthouse in the country after the Supreme Court Building in Washington DC. The building, constructed in 1932–1933, features walls of Arkansas limestone and a base of Texas pink granite. It houses separate ZIP codes. A photographer’s island allows people to take pictures of subjects straddling two states.

Museums on the Arkansas side include the Tex-Arkansas Antique Auto Museum, representing more than fifty years of automobiles. Other Texarkana museums include the Museum of Regional History and Wilbur Smith Research Library, the Discovery Place Children’s Museum, and the Ace of Clubs House, a restored historical home built in 1885.

Texarkana has at least ten annual festivals, including the Jump, Jive & JamFest in April; Sparks in the Park on the first Saturday in July; the Quadrangle Festival over Labor Day weekend; the Four States Fair and Rodeo in September; Texarkana RV Music Park festivals on Memorial and Labor Day weekends; the Mistletoe Fair in November; and the Twice as Bright Festival of Lights from Thanksgiving to New Year’s.

Lake Millwood and Lake Wright Patman abound with outdoor activities. Oaklawn Opry showcases country and western music performers.

Education

The Texarkana Arkansas School District enrolls about 5,000 students. There are five elementary magnet schools, three junior high learning academies, and the Freshman Academy at Arkansas High School. Also on the Arkansas side is the Texarkana Airframe and Powerplant School operated by Southern Arkansas University in cooperation with Texarkana College and area high schools. In fall 2012, a branch campus of the University of Arkansas Community College at Hope (UACCH) opened in Texarkana. Due to the growth of this campus, UACCH was renamed University of Arkansas Hope-Texarkana (UAHT) in 2019.

Notable Figures

Magician J. B. Bobo was known for his performances and books. Thomas Hinton was a classical painter. Politician William Kirby was on the Arkansas Supreme Court and also served as state attorney general and U.S. senator, while politician June Carter Perry worked for the U.S. State Department and as a U.S. ambassador. Samuel Nancarrow was a piano player and music composer. Willie Davis grew up in Texarkana and had a successful career with the National Football League before entering the business world. Gilbert Cook was a career U.S. Army officer who distinguished himself in both World War I and World War II. Wayne Dowd had a long tenure in the Arkansas Senate, during which he oversaw a significant reform of juvenile justice laws. John F. Stroud Jr. was an advisor to some of the state’s top political and judicial figures and spent ten years on the appellate bench himself. Right-wing advocate Billy James Hargis was born in Texarkana.

Susan Webber Wright (later Susan Webber Carter) was a U.S. district judge who became widely known for presiding over the Paula Jones sexual harassment lawsuit brought against U.S. president Bill Clinton. Wright later made headlines again when she found Clinton to be in contempt of court. Businessman and consultant Bob J. Nash most notably served in the administration of Governor Bill Clinton in the 1980s and in the administration of President Clinton in the 1990s.

For additional information:

Artifacts: Newsletter of the Texarkana Historical Society & Museum. Texarkana, AR: Texarkana Museums and Historical Society (1986–).

Davis, Doris Douglas. The Ahern Home of Texarkana. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2024.

Jennings, Nancy Moores Watts, compiler. Texarkana Pioneer Family Histories: Texarkana, Arkansas-Texas. Texarkana, AR: Texarkana Roarck, 1961.

Leet, William D. Texarkana: A Pictorial History. Norfolk, VA: Donning, 1982.

Texarkana Centennial Historical Program, 1873–1973. Texarkana, AR: Texarkana Historical Society and Museum, 1973.

Texarkana Chamber of Commerce. http://www.texarkana.org (accessed August 31, 2022).

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Texarkana was laid out as early as 1856, as a supposed meeting point between the Cairo & Fulton; Mississippi Ouachita and Red River; and Memphis, El Paso and Pacific (of Texas) railroads. That’s the earliest the name appears in newspapers. There is evidence that it was a community as early as 1849, founded by Josiah W. Fort, and according to the January 27, 1885, issue of the newspaper “Town Talk” in Alexandria, LA, the town was named by chief engineer of the M,EP&P, Fortunatus S. Mosby, as only a combination of Texas and Arkansas, sans Louisiana. Mosby names Fort in his chief report for the railroad as a prominent funder in the area, excited to have the railroad built, throwing the first blade of dirt to conceive construction. F. S. Mosby had been under the wing of Lloyd Tilghman, the well-known railroad engineer from Kentucky, who was at this time building the Mississippi Ouachita and Red River from Eunice, Arkansas, on the Mississippi River to Dooley’s Ferry on the Red, sixteen miles below Fulton. Tilghman recommended Mosby as a chief engineer to the shareholders of the M,EP&P to build a “Western division” of a great Pacific Railroad. The grand scheme was that the Memphis & Little Rock, Cairo & Fulton, and the MO&RR Railroads were going to be the leading lines of the “Southern Transcontinental Railroad” routes to the California coast, with Texarkana/Texarkana being the bottleneck and the M,EP&P leading the charge out West. Of course as with most pre-Civil War projects, this never came to fruition and Texarkana would have to wait until the C&F reached it in 1874 to become an economic hub.

Gus Knobel was in the area as an engineer for the C&F, but more likely he was refreshing a town name than actually coming up with the moniker himself.

I was born seventy-six years ago at 421 Main St., Texarkana, Texas, and grew up there until age 12. I attended Central Elementary.

Your history is well done, and I think you covered most things. You left out Spring Lake Park, though, which all the kids and adults loved for many years, and its history. Also, there was a great swimming pool where everyone went on the Texas side. I think it was called Brammillers or something like that.

My mothers family came to Texarkana around 1880 and are all buried at the cemetery on State Line Ave. No living family left.

I am Jewish, and I know that many major early improvements in the city were founded by Jewish residents who played a major role in the development.