calsfoundation@cals.org

Rice Industry

Rice, the most popular grain in the world, is Arkansas’s leading agricultural product. Although it was only rarely grown in Arkansas before the twentieth century, rice came to dominate eastern Arkansas farms, beginning in the Grand Prairie but rapidly expanding into the Mississippi Delta and the Arkansas Valley.

Domesticated rice (Oryza sativa) is not native to North America. It has been cultivated in central Asia for up to 6,500 years, and its use gradually spread to eastern and western Asia, the Mediterranean basin, and Africa. Roughly 40,000 official varieties of rice are recognized, but they usually are sorted into three categories: short-grain, medium-grain, and long-grain. While most rice is consumed as a grain, rice is also an ingredient in many other products, including pet food and beer. Rice fields are also an important habitat for many animals, including migrating waterfowl.

Rice was first introduced to the western hemisphere when it was planted in South Carolina in 1694. Its cultivation spread slowly through the southeastern United States. Thomas Nuttall reported seeing rice cultivated at Arkansas Post in 1819. Later, around 1840, some farmers in Arkansas experimented with rice as a crop, but they found that maintaining proper growing conditions for the grain was difficult. Rice grows best in flooded fields, but it is easier to plant and to harvest when the ground is dry. Nineteenth-century technology did not offer affordable solutions to the problem of irrigating fields on the schedule that a rice crop requires.

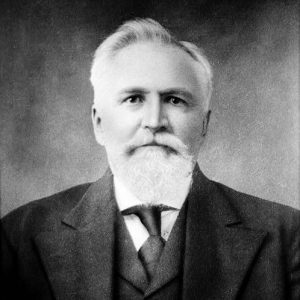

Several Arkansas farmers experimented with rice in the opening years of the twentieth century, but William H. Fuller of Carlisle (Lonoke County) has become the legendary father of the Arkansas rice industry. Fuller, who had come to Arkansas from Nebraska to farm, was on a hunting trip with friends in Louisiana in 1896 when he first saw rice being cultivated. Noting similarities between the Louisiana soil conditions and those of the Grand Prairie, he resolved to experiment with rice on his own land. Investing $400 in pumps and other equipment, Fuller planted three acres with rice in 1897. Not encouraged by his initial results, Fuller moved to Louisiana and worked on rice farms there for several years, learning the techniques that had proven successful. Returning to Arkansas in 1903, Fuller met with several businessmen in Hazen (Prairie County) who offered to pay him $1,000 if he could raise thirty-five bushels of rice per acre on his farm in either 1904 or 1905. Purchasing a well rig and other material in Louisiana as well as seed rice, Fuller planted seventy acres with rice in 1904 and produced a crop of 5,225 bushels of rice, more than double the output required to claim the $1,000 bonus. His example, coupled with other successful plantings, prompted a growing number of Arkansas farmers to begin cultivating rice.

Rice cultivation did not immediately replace cotton fields; more often, rice was planted on land that had been used for grazing livestock or that had recently been cleared of timber. Levees and pumps, as well as new machinery designed to remove tree stumps at or below ground level, were required to create and maintain rice fields. Seasonal flooding of the St. Francis and Cache rivers made some Arkansas land unsuitable for other crops but ideal for rice. Many rice farmers, like Fuller, were recent immigrants to Arkansas. A survey taken in 1930 revealed that sixty percent of the landowners in Arkansas cultivating rice had come to the state from Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, or Ohio. These rice farmers did not adopt the sharecropping system that was common in raising cotton, preferring instead to pay wages to their laborers, many of whom were migrant workers, while others lived near the rice farms, planting in the spring, harvesting in the fall, and clearing additional land in the winter.

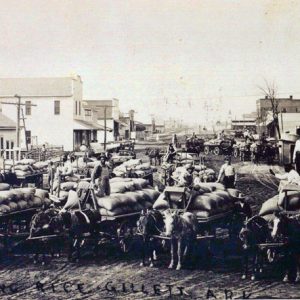

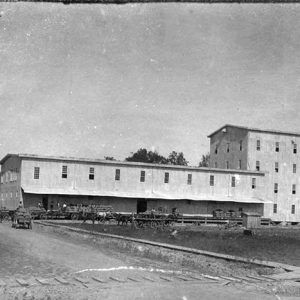

One of the earliest challenges to raising rice in Arkansas was the cost of shipping the harvest to mills in Louisiana. The first rice mill in Arkansas opened in Stuttgart (Arkansas County) in 1906. Four more had been added by the end of 1910. World War I dramatically increased the market for Arkansas rice, and many more rice farms were established. Cities such as Stuttgart, Des Arc (Prairie County), and DeWitt (Arkansas County) grew dramatically as a result. The end of the war brought a sharp decline in prices, and rice farmers decided to meet the challenges of a fluctuating economy by organizing. The Arkansas Rice Growers Cooperative Association was formed in 1921. This association eventually became Riceland Foods, the world’s largest rice miller and rice marketer, which later expanded to market other crops, including soybeans. Riceland operates one of the world’s largest rice mills in Jonesboro (Craighead County). With 9,000 member farmers in five states, Riceland employs nearly 2,000 workers to receive, store, transport, process, and market rice, wheat, and soybeans.

Like other agricultural industries, the rice industry in Arkansas was challenged by the Flood of 1927, the Flood of 1937, the Drought of 1930–31, and the Great Depression. A rice reduction program was attempted in 1933 and in following years as part of the New Deal, but rice farmers felt that the program was not helpful to them. World War II sparked new opportunities for rice marketing; in 1942, 268,000 acres had been devoted to raising rice in Arkansas, resulting in a yield of 13.196 million bushels of rice. Increasing mechanization of planting and harvesting revolutionized the industry during the middle years of the twentieth century.

Concerns about depletion of the water table in the Grand Prairie had been expressed as early as 1916, and the 1950 Flood Control Act passed by the U.S. Congress sought to address these worries by directing the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to design a system helping rice farmers to irrigate their fields with water from the White River. The Grand Prairie Area Demonstration Project, authorized by Congress in 1991, continues to be challenged by environmental advocates who fear that other parts of the White River valley will suffer from the results of the project. Environmentalists also express concerns about the high-nitrogen fertilizer used on many rice fields, as well as the spread of pesticides into the state’s water supply.

The importance of the rice industry to Arkansas’s economy is reflected by the construction of the Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center, which opened in Stuttgart in 1998. Federally funded through the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the center employs scientists in a wide range of research topics, seeking to benefit rice producers and also to protect the environment from potential harm resulting from rice farming.

In 2017, Arkansas rice producers harvested 1,104,000 acres, with a state average yield of 164.4 bushels/acre (7,400 pounds/acre). Rice is grown in forty counties and ranks as one of the top three crop commodities, in terms of cash receipts, for Arkansas farmers. Arkansas leads the fifty states in rice production; about eighty percent of American rice is grown in Arkansas, Louisiana, and California. While other states grow largely short-grain rice, Arkansas farms produce more long-grain rice. Ninety percent of the rice consumed in the United States is grown in the country, and the United States also is one of the world’s largest exporters of rice.

In 2006, a strain of genetically engineered long-grain rice produced by Bayer Crop-Science was found inadvertently mixed into the rice crop in Arkansas. Though the rice was safe to eat, this strain was banned in the European Union, Japan, and other countries and had been intended only for animal feed. The price paid for Arkansas rice dropped dramatically as various countries banned its import. Five years later, after a series of court cases, a $750 million settlement was reached, involving payments to Arkansas rice farmers to compensate them for the loss of income.

The Arkansas General Assembly voted in 2007 to make rice Arkansas’s official state grain. Rice was included in the design of the Arkansas State Quarter, distributed in 2003. The Arkansas Rice Festival, held in Weiner (Poinsett County) every October since 1976, draws thousands of visitors each year, many of them from out of state.

The University of Arkansas Rice Research and Extension Center (RREC), one of five research and extension centers in the University of Arkansas System’s statewide Division of Agriculture, is one of the oldest rice research centers in the world, having begun in the 1920s. Ground was broken in May 2023 for the Northeast Rice Research and Extension Center in Harrisburg (Poinsett County), owned and operated by the UA System Division of Agriculture, which will conduct research to serve the rice growers of northeastern Arkansas. In addition, scientists with the Arkansas Biosciences Institute have been researching rice strains that would be resistant to the hotter nights brought on my global warming.

For additional information:

Arkansas Rice Research and Promotion Board. http://www.arkrice.org/ (accessed February 7, 2022).

Carter, L. Clyde. “Oral History.” 1970. Audio online at Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Arkansas Studies Institute (ASI) Research Portal: L. Clyde Carter Oral History (accessed February 7, 2022).

Fuller, W. H. “Early Rice Farming on Grand Prairie.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 14 (Spring 1955): 72–74.

Gates, John. “Groundwater Irrigation and the Development of the Grand Prairie Rice Industry.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 64 (Winter 2005): 394–413.

Langhorne, Will. “Scientists Study Climate-Change Stresses on Rice.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 5, 2023, pp. 1A, 6A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/jul/05/researchers-race-to-save-rice-one-of-arkansas/ (accessed July 5, 2023).

Larue, Cristina. “Isbell Farms Values Sustainability.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 1, 2022, pp. 1D, 2D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/oct/01/isbell-farms-values-sustainability/ (accessed October 3, 2022).

Lee, Jeon. “The Historical Geography of Rice Culture in the American South.” PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1988.

Mahon, J. C. “The History of Riceland Foods.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 17 (Summer 1979): 10–17.

Rosencrantz, Florence L. “The Rice Industry in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 5 (Summer 1946): 123–137.

Steven Teske

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.