calsfoundation@cals.org

Ten Percent Plan (Reconstruction)

The Ten Percent Plan was the first official Reconstruction policy unveiled by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. The policy was announced by President Lincoln in December 1863 and was aimed at shortening the war by offering comparatively merciful terms for Confederate states to leave the Confederacy and rejoin the Union. Through this plan, Arkansas Unionists would begin the process of forming a new, loyal state government recognized by federal officials.

After the fall of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Little Rock (Pulaski County) to the Union army in 1863, Arkansas was effectively split into zones under Union control and Confederate control. Unionists were emboldened by the success of the U.S. Army and began working to solidify the collapse of Confederate control over most of Arkansas.

By October 23, 1863, Unionists meeting in Fort Smith called for fellow Unionists across the state to meet in their counties to organize delegates for creating a new, loyal government. President Lincoln saw Unionists in Arkansas and across the Upper South speaking out and used this as an opportunity to shorten the war. On December 8, he issued his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction (his first Reconstruction plan), stating that if ten percent of those voters who had been qualified to vote in 1860 swore an oath of loyalty to the United States and rejected secession, they could form a new Union government and would be pardoned for any participation in the Confederate army or government. Unionists in Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia would ultimately form loyal governments based on this plan.

In the 1860 election in Arkansas, 54,152 men had cast their ballots. This meant that 5,415 voters would have to take the loyalty oath. Several counties, particularly in northern Arkansas and already under Union control, voted strongly for avowedly Unionist candidates like former senator John Bell of Tennessee and Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (Lincoln was not on the ballot in Arkansas).

Union general Frederick Steele echoed President Lincoln’s proclamation on December 8, 1863, endorsing the organization of a Unionist government in the state. With Confederate forces falling back across Arkansas, it appeared the Confederacy was crumbling. Union enlistments surged, and Confederate desertions accelerated, and almost 15,000 Arkansans were fighting in the U.S. Army by the end of 1863.

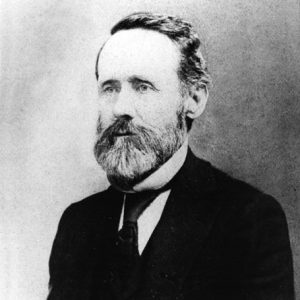

Dozens of delegates were chosen for a convention to draw up a new state constitution. The new convention began on January 4, 1864, in Little Rock. However, attendance was sporadic in the often disorganized meetings. John McCoy of Newton County was elected as president of the convention. Union general Powell Clayton, a later governor, noted that no more than twenty-three counties were represented at any one time, and no more than forty-five delegates were present at any time. Sixteen counties in southern Arkansas had no representation at all, including Ashley, Calhoun, Chicot, and Union. Southern counties such as Columbia and Ouachita were able to send delegates.

Confederate officials who gathered at the small community of Washington (Hempstead County), which effectively became the new Confederate capital of the state, denounced the convention as illegitimate. The state was effectively divided, with several counties having delegates at both the Unionist convention in Little Rock and the Confederate state legislature at Washington.

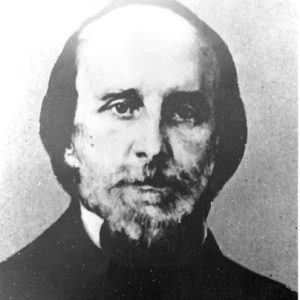

Isaac Murphy of Madison County, the lone holdout against Arkansas secession at the secession convention in 1861, was immediately chosen interim governor at the convention. Abolitionist Calvin Bliss, a Vermont native and Batesville (Independence County) school teacher, was selected as interim lieutenant governor. Robert White of Crawford County, secretary of the convention, was chosen as interim secretary of state.

The document that emerged was similar to the state constitutions of 1836 and 1861 in many respects, with two major exceptions. One was the creation of the office of lieutenant governor for the first time. The other was the total ban on slavery in Arkansas. (In 1860, there had been more than 111,000 slaves in the state, a quarter of the total population.) With Confederate forces on the run, there were fewer officials or planters in the southern part of the state who could enforce the institution. With the backing of the Union army in the northern half of the state, slaves not already freed were running to the freedom that the army’s protection offered. However, the new constitution left the legal status and rights of the freed slaves ambiguous.

An election was held to ratify the new constitution in March 1864, a difficult matter since many counties were still under Confederate occupation. Of those who were able to vote, the response was overwhelming: ninety-eight percent of voters approved the new constitution. Of the more than 12,000 voters in a wartime election, only 266 people voted against the constitution. Murphy, Bliss, and White were all elected without opposition. Legislators were elected from forty-five counties for the legislative session slated to begin in April.

When the new government convened on April 11, it presided over a state where slavery had become illegal, but also a state bitterly divided and still fighting a war of neighbor against neighbor. They also faced the overwhelming task of rebuilding a state torn apart by the Civil War, and one having to contend with the chaos of continuing warfare, refugees, and bandits. In spite of the new civilian Unionist government, the state was effectively under control of the army.

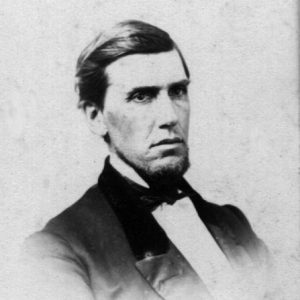

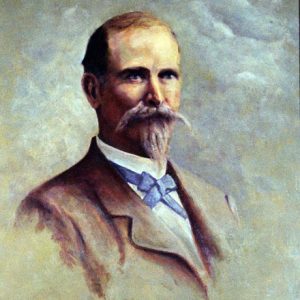

Murphy and Bliss were formally inaugurated on April 18. William M. Fishback of Sebastian County and Elisha Baxter of Independence County, both future Arkansas governors, were chosen by the legislature as U.S. senators in May; the U.S. Senate refused to accept them, however. Many members of the U.S. Congress were skeptical of the loyalty of the new Ten Percent governments. Congress refused to readmit Arkansas under Lincoln’s plan. Arkansas was unable to seat a congressional delegation and did not participate in the 1864 presidential election as a result.

The Confederate army and the Arkansas Confederate government had both collapsed by February 1865. Unable to find anyone willing to negotiate with him or even acknowledge him, Confederate governor Harris Flanagin of Arkadelphia (Clark County) dissolved the Confederate government in the state by sending all Confederate government records by wagon to Little Rock, signaling the end of all remaining claims.

By this time, the U.S. Congress had passed an amendment formally ending slavery, which would become the Thirteenth Amendment. It was now up to the states to finish the ratification process, which would require the approval of three-fourths of the states. Gov. Murphy called for a special session of the state legislature to ratify the amendment on February 16. The session was scheduled to begin on April 3. When the session opened, however, it was still several more days before a quorum was reached.

Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered his forces in Virginia on April 9, leaving only a handful of scattered units and resistance across the South. Upon hearing the news of Lee’s surrender by telegraph, state Representative Jesse Shortis of Benton County called for a resolution the next day thanking Union forces for their work and marking “the beginning of the end” of the war and “a speedy restoration of the Union.”

On April 12, Governor Murphy’s message to the legislature calling for ratification was read. The legislature voted to move a discussion and vote to April 14. Murphy called ratification of the amendment abolishing slavery “the great act that will consolidate the Union of the States on the basis of equality, politically and socially; remove the cause of our troubles and bind together all the States in a Union of interest and affection.” State representatives L. M. Harris of Van Buren County and J. H. Demby of Montgomery County announced they would be sponsoring a joint resolution in favor of ratification.

On April 13, the state Senate voted unanimously to ratify the amendment. The state House of Representatives followed on the next day, Good Friday, with all representatives voting to ratify the amendment. Arkansas was the fourth former Confederate state to vote to ratify the amendment. Arkansas even managed to ratify the amendment ahead of long-standing free Union states as Iowa, New Hampshire, and Connecticut.

The ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment was effectively the last act of the Arkansas legislature under Lincoln’s Reconstruction plan. Later on the night of April 14, Lincoln was shot and mortally wounded at Ford’s Theater in Washington DC. He died the next day, a passing that was met with great mourning by legislators. Vice President Andrew Johnson would become president and initiate his own Reconstruction plan.

For additional information:

Arkansas Constitutional Convention. Journal of the Convention of Delegates of the People of Arkansas: Assembled at the Capitol, January 4, 1864. Little Rock: State of Arkansas, 1864.

C. C. Bliss Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography, 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Isaac Murphy Papers. Kie Oldham Collection. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

MacPherson, James M. Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 3rd ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Smith, John I. The Courage of a Southern Unionist: A Biography of Isaac Murphy, Governor of Arkansas, 1864–68. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1979.

Whayne, Jeannie, et al. Arkansas: A Narrative History, 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2013.

Kenneth Bridges

South Arkansas Community College

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Elections during the Civil War

Elections during the Civil War Politics and Government

Politics and Government Elisha Baxter

Elisha Baxter  Calvin Bliss

Calvin Bliss  Powell Clayton

Powell Clayton  William Fishback

William Fishback  Isaac Murphy

Isaac Murphy

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.