calsfoundation@cals.org

Stay More Series

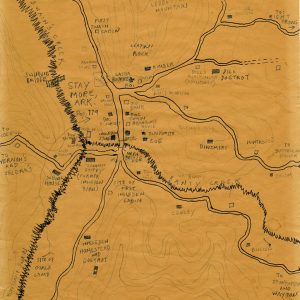

“Stay more,” according to Arkansas novelist Donald Harington, was the polite entreaty that settlers of the Ozarks would use at the end of a visit to keep their guests from leaving. Visitors who knew their mountain manners would never simply decline the invitation, but instead respond with an equally polite counter-invitation to their hosts to come home with them. The leave-taking formality could go on and on, with host and guest affirming over and over their affection for the other’s company and their reluctance to give it up.

“Stay More” was also the name of the fictional Ozarks town that Harington created and returned to many times in thirteen of the fifteen novels he published during his lifetime. The origins of Stay More were deeply embedded in the author’s personal experience. Born in 1935 in Little Rock (Pulaski County), Harington developed his love of the Ozarks while spending summers with his maternal grandmother in the small mountain town of Drakes Creek (Madison County), absorbing the local accents and idioms from the residents, who nicknamed him Dawny. Listening to the tall tales and humorous yarns they shared with each other from their porches in the evenings, Harington developed an abiding love of mountain speech and of the lives that produced it, a love that took on new urgency when, at the age of twelve, he contracted a case of meningococcal meningitis that cost him his hearing. The next summer, Harington holed up in Drakes Creek, reading his way through novels by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Miguel de Cervantes, and others, immersing himself in the written word to cope with a newfound sense of loneliness. The author’s careful phonetic renderings of the backwoods dialect he had so fallen in love with as a child in Drakes Creek were part of an effort to preserve a way of life that had been, in its most immediate and natural form, taken away from him.

These childhood experiences, both pleasurable and painful, helped Harington to invent Stay More and to eventually produce a body of work that prompted Entertainment Weekly to label him “America’s greatest unknown novelist.” Like William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha, Stay More provided Harington with a remote but deeply rooted setting to play out the lives of a tight-knit community across the years, sometimes serving as a microcosm of American history and culture and, at others, as an illuminating exception. In Harington’s treatment, the residents of Stay More, affectionately known as “Stay Morons,” were provincial but competent, protective but polite, isolated but engaged, idiosyncratic and fiercely independent but also loyal and staunchly grounded in their identities as Ozarkers and Americans.

Stay More first appeared in Harington’s second published novel, Lightning Bug (1970), which introduces the reader to Latha Bourne, the “demigoddess” of Stay More, the undying muse who reappears throughout his work as an embodiment of beauty and spiritual freedom. Lightning Bug’s primary timeline finds Latha serving as the postmistress of Stay More during the Great Depression and caring for her niece, who spends summers in Stay More away from her parents in Little Rock. But like other Harington novels, it incorporates other timelines, including Latha’s adolescent relationships with Raymond Ingledew and Every Dill, who vie for her attention in Stay More and end up in the same fateful firefight in World War I, and her commitment to a mental institution in Little Rock shortly after giving birth to a daughter some years later. Perhaps most importantly, the novel establishes Latha’s relationship with Dawny, who shares the author’s nickname and eagerly awaited summers in the Ozarks. Though just five years old when the book opens, Dawny is hopelessly in love with Latha and her ghost stories, and he swears to remain so forever, the two of them showing up at various stages of their lives throughout subsequent novels.

Though Harington had planned to bid farewell to the Ozarks as a setting after this novel, Stay More continued to play a prominent part in all of his subsequent work (with the exception of Let Us Build Us a City), including the other two novels he published in the 1970s. In Some Other Place. The Right Place. (1972), Stay More is disguised as “Stick Around” and serves as the final destination for dancer Diana Stoving and Eagle Scout Day Whitacker, who is a medium for Diana’s mysterious grandfather, Daniel Lyam Montross, a poet long dead when the novel opens, whose own travels from New England to Stick Around under increasingly dangerous circumstances are retraced by Diana and Day. The farther they go, the more complicated the connections between their lives and Montross’s become, Diana hypnotizing Day to get Montross to eventually reveal his full life story to her, Day falling in love with Diana even as he grows increasingly uncomfortable with her ability to replace his voice with Montross’s. The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks (1975), in sharp contrast, takes a macroscopic perspective to serve as what the author called the “Bible of Stay More,” covering almost two centuries of the town’s history as told through the lives of the generations of the Ingledew family, the first settlers in the area. The novel is also framed as a lecture on the evolution of architecture in the region, proceeding from the double-hovel of Fanshaw, an Osage Indian who preceded the Ingledews in the area, to the double-bubble mansion of Vernon Ingledew, a polymath autodidact who is to run for governor of Arkansas in the late twentieth century and be the last of the Ingledews.

Harington referred to the decade that followed the publication of Architecture as his “dark ages,” a period in which he lost his father, his job, and his first marriage. It was not until the late 1980s, after he had remarried, landed a teaching position at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), and won over an editor at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich that Harington resumed the story of Stay More with a series of unusual novels that demonstrated the remarkable versatility of his remote Ozark town as a setting for narrative fiction. The Cockroaches of Stay More (1989) resets Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles into a community of cockroaches (or “roosterroaches,” as Harington playfully euphemizes them) living in the almost deserted town during the 1980s. Harington uses the scenario not only to advance the story of the Ingledews’ distant descendants, but also to satirize religious hypocrisy in the form of the rapturous Crustian roosterroaches, who worship the highly fallible (and perpetually drunk) Man, all of these intrigues embedded within a Cold War fable of the terrors of nuclear war. In The Choiring of the Trees (1991), Harington offered his version of a prison novel, with Stay More shepherd Nail Chism wrongfully convicted of rape and sent to death row in a brutal prison in Little Rock in the early twentieth century. Nail’s story was partly inspired by that of an actual Ozark mountaineer who was condemned to die, with Nail, too, escaping the electric chair more than once, in his case with the help of artist Viridis Monday, who has learned about Stay More and the truth of the charges in her research into Nail’s conviction.

Next up was Ekaterina (1993), in which Harington pays tribute to his favorite writer, Vladimir Nabokov, and his most famous novel, Lolita (1955), by telling the life story of Ekaterina Dadeshkeliani, an exiled princess from Svanetia who is also an expert mycologist and a fancier of pubescent boys. Kat escapes Soviet persecution to come to America, where she is tutored in writing by the grown-up Dawny (by now a depressed, alcoholic middle-aged novelist), who brings her to Stay More; she eventually takes up residence in a haunted hotel in a lightly fictionalized version of Eureka Springs (Carroll County) and comes to serve as perhaps the author’s most ingeniously constructed set of narrative masks in this nesting doll of a novel. Harington followed up his Nabokov tribute with Butterfly Weed (1996), his doctor novel, which uses a conversation with dying Ozarks folklorist Vance Randolph as a frame for the story of Stay More native Colvin Swain, the seventh son of a seventh son and Harington’s Ozark version of Asclepius, the classical Greek physician. The exuberantly ribald story of Doc Swain and his magical dream cure allows Harington to adapt various myths and mythological figures from the Greek pantheon to Stay More, where Colvin falls in love with his student, Tenny Tennyson, whose tuberculosis defies even the dream cure, all in a poignant tale that evokes the hopeless love of Eros and Psyche.

Butterfly Weed was Harington’s last novel for Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, so he had to find new publishing homes for his follow-up war novel and political novel. Counterpoint Press brought out When Angels Rest (1998), which returns Dawny, now eleven years old, to center stage during World War II, organizing war effort drives, publishing a local newspaper filled with war headlines and local gossip, and engaging in war games with the other children of Stay More. Dawny’s innocence undergoes a severe trial when war shows up in reality in the form of an army battalion that uses Stay More to stage simulations of a ground invasion of Japan, replete with tanks and explosive munitions. Four years later, publisher Henry Holt brought out Thirteen Albatrosses, or Falling Off the Mountain (2002), in which Harington tells the story of Vernon Ingledew’s campaign for governor, an effort complicated by his extremely impolitic plans to eradicate schools and hospitals, two of the “albatrosses” his advisors identify as challenges to his electability. Another challenge takes the form of his improbable romance with the last Osage descendant of Fanshaw, millionaire Juliana Heartstays, who is initially determined to kill Vernon and reclaim Stay More from the settlers who have dominated the region for two centuries.

When both Counterpoint and Holt abandoned Stay More after one book each, Harington queried more than seventy potential publishers before finding Toby Press, which published With (2004) and soon republished the entire Stay More saga. The horrifying scenario for With certainly complicated the author’s search. Police officer Sog Alan, who appears as a violent bully in many of the earlier Stay More novels, retires from the force by abducting his “truelove” Robin Kerr, the seven-year-old daughter of a store clerk in Harrison (Boone County) and spiriting her off to an inaccessible hideout in the mountains high above Stay More. But this excruciating set-up soon turns into an exhilarating story of determination, resourcefulness, and triumph. Robin continually finds ways to outdo her namesake, Robinson Crusoe, in surviving not just her abductor, but also the challenge of having no one to rely on but herself, accompanied only by an ever-increasing circle of animals and her own generous imagination, through droughts, floods, and deadly cold winters. Robin’s tale serves, in some ways, as a concentrated counterpart to the story of Latha Bourne, both of them survivors who set down deep roots in Stay More that help them endure and even flourish within the almost overwhelming solitude that was a favorite theme of their author.

After With, Harington would publish three more novels, all with Toby Press. The first two of these were completely different from each other. The Pitcher Shower (2005) was dedicated to Matthew Miller, the director of Toby Press, and tells the story of Hoppy Boyd, an itinerant movie exhibitor (or “show-er,” in Ozarks dialect) during the Depression who drives his combination pickup truck and projection booth around to small towns in the Ozarks to play black-and-white Westerns for the appreciative audiences. Harington supplies Hoppy with a nemesis in the form of hellfire-and-brimstone preacher Emmett Binns, who pursues Hoppy and preaches against the immorality of his “pitcher shows,” and with a mysterious assistant named Carl, who eventually causes Hoppy to unintentionally recreate elements of the beloved William Shakespeare comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The next-to-last Stay More novel, Farther Along (2008), brings Harington’s first novel into the Stay More fold as a kind of belated adoptee, sending Clifford Stone, the protagonist of The Cherry Pit (1965), which was originally not part of the series, off to the cliffs above Stay More to live as the original pre-settler inhabitants had. Referred to only as the Bluff Dweller, Clifford eventually encounters Latha Bourne and scholar Eliza Cunningham, whose company draws him increasingly out of his hide-out in the caves to learn the story of Stay More. Framed partly as an epistolary novel, Farther Along takes its name from the funeral anthem of Stay More, a hymn that is always sung at funerals to express both resignation and resolve.

These themes carry over beautifully into Harington’s final novel, Enduring (2009), which was published just two months before his death. To end everything, Harington returned to the story of Latha Bourne to present her life in full, overlapping with many episodes covered in earlier novels, but extending and deepening the account with details from her childhood, adolescence, and old age that fill out the portrait of the demigoddess of Stay More, well over 100 years old when the book opens but still going strong, eventually outlasting even her own author. The book ends by refusing an ending, with Harington’s signature shift to the future tense in the final chapter serving to keep the story existing forever into an as-yet unlived future. That final chapter, in particular, works to fulfill both the pain and the promise of the haunting, wishful name that Harington had bestowed on his fictional town so many decades earlier.

The author’s struggle with his sense of enforced isolation, fought imaginatively throughout the Stay More novels, took telling forms in his life as well. Above the door of his study, Harington posted a sign that read “Stay More, Pop. 1.” When a friend suggested that he was not actually alone there, that he was always joined in Stay More by the Gentle Reader to whom he addresses one of his late novels, Harington happily crossed out the original number and doubled the population of his fictional town.

For additional information:

Razer, Bob. “Donald Harington and His Stay More Novels: A Celebration of Thirty-Five Years.” Fayetteville: Special Collections Department, University of Arkansas Libraries, 2006.

Walter, Brian, ed. Double Toil and Trouble: A New Novel and Short Stories by Donald Harington. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

———. The Guestroom Novelist: A Donald Harington Miscellany. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Brian Walter

St. Louis, Missouri

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.