calsfoundation@cals.org

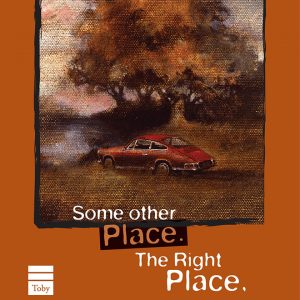

Some Other Place. The Right Place.

Donald Harington filled his third novel, 1972’s Some Other Place. The Right Place. (abbreviated as SOP. TRP.), with memorable phrasings, multivalent puns, and metafictional flourishes, but no line in the book resonates more deeply or delightfully than this one: “Go to sleep, Day.” “Day” is the teenage companion, lover, and eventual life partner of protagonist Diana Stoving, and her four-word command opens up an entire world of narrative and philosophical possibility for the longest and perhaps most ambitious novel Harington ever wrote.

“Go to sleep, Day” is what Diana says to Day when she wants to hear more of the story of Daniel Lyam Montross, her grandfather, a Connecticut Yankee who died mysteriously in the Ozarks when she was three years old and in his keeping. The command hypnotizes Day, transforming him into a medium to channel her dead grandfather.

One of the many ways to read this novel is as Diana’s quest for a stable sense of self, something she lacks at the beginning of the book, cut adrift after her recent graduation from Sarah Lawrence College, unsure of what she wants to do with her life. Day’s spiritual connection to her grandfather gives Diana a sense of purpose: to learn the story of Daniel’s far-wandering life and her own place within it. Moving from place to place where her grandfather lived during his life, putting Day to sleep to tell Daniel’s story at each period, Diana makes a superb Harington protagonist, a restless soul who intuitively and needfully blends time and space, bringing the past profoundly into the present. She is a capable, even resourceful person, but also lonely and vulnerable.

The other two main characters of the novel, Day and Daniel, are just as haunted as Diana, and in their hauntings, they, too, serve as building blocks for Harington’s Stay More saga. Day is, like Diana, a recent graduate, but of high school, not college, and his experience and skills as a decorated Eagle Scout and amateur expert in forestry prove to be as important to their long sojourn away from civilization as Diana’s money (the gift of rich parents who are largely absent from the story).

Through his stories, Grandfather Daniel, a child of a large family that was poorly equipped to take care of him or his siblings, introduces Diana and Day to the world of American folk culture. Daniel lives a hardscrabble life wherever he lands, and the idiomatic expressions he uses to describe his world frequently confound Diana and Day, requiring lesson after lesson in the linguistic quirks of old timey New England farm life.

To work his way through the intertwined stories of these characters, Harington divided SOP. TRP. into five different musical parts, an overture and four subsequent movements. In anticipation of several of his later novels (including Ekaterina, Thirteen Albatrosses, and With), Harington shifts to different narrative personae and perspectives with each movement. These shifts incorporate a fourth character into the drama: G., a restless Arkansas novelist and college professor (like Harington) who decides—in a bit of metafictional cleverness—that he will become the detective who finally tracks down the story of Diana and Day months after they have disappeared, seemingly for good. The first part of the novel, the overture, consists of G.’s reconstruction of Diana’s story from the clues he was able to pick up about the journey that Diana and Day take as they themselves track the life wanderings of Daniel Lyam Montross.

The first and second movements belong, respectively, to Day and Daniel. Day is a self-conscious stylist, lamenting his inability to muster the kind of sophistication that the better educated, more artistic Diana has brought to her journals, which serve as the basis for the overture section of the book. His devotion to her is all the more apparent and appealing, and his doubts and frustrations about serving as the medium for her grandfather, a man she often seems far more interested in than Day himself, drives Day’s narrative installment to a nervy cliffhanger ending that cleverly, fatefully, brings his Eagle Scout expertise to bear.

For his part, Daniel Lyam Montross is everywhere and nowhere in the book. Harington accentuates his voice by literally bolding the text of his narration, distinguishing it visibly from Day’s and Diana’s stories and speech. But having died decades before the book opens, Daniel makes for a ghostly presence. Harington plays endlessly and inventively with the connections between Daniel and his living medium Day, sometimes having a sentence that begins in Day’s normal font continue directly into Daniel’s bold story. For one stretch of the novel, in fact, Harington blends them even more dizzyingly, alternating lines of regular and bold font as he interlaces Day and Diana’s story literally line by line with Daniel’s. Part of Daniel’s job in sharing his story within Diana’s and Day’s story is to liberate them from the future by cultivating the past, grounding them in their heritage and in the different natural settings that his wanderings bring them to. Harington embeds Daniel still deeper into the story by making the third movement consist of nothing but the old Connecticut Yankee’s poetry, first from a volume called Montross: Selected Poems and second from a collection called The Ghost’s Song and Other Poems.

Harington brings this heady metafictional brew to a boil in the fourth and final movement, when G. in fact catches up to Diana in Stick Around, the disguise that Harington uses for Stay More in this book. When Harington’s avatar G. finally, after months of pursuit, meets his heroine, she is alone (Day is off in the woods working on a long-term forestry project), pregnant, and entirely unwilling to cede her reality to skeptical G.’s. Much of the fourth movement consists of a clever chess match between the heroine and her metafictionalized author, G., who insinuates that the love letters Diana exchanges with Day are fabrications, pretend correspondence that she writes for herself. Diana, for her part, insists that G. just needs to stick around and learn more about Daniel Lyam Montross while waiting for Day to return. The contest between heroine and author is further braided into the climax of Daniel’s story.

Frustrated with agents and editors who made promises they did not keep, Harington eventually found a new publisher for SOP. TRP. in Little, Brown, which had loved Lightning Bug. In the end, even though SOP. TRP. was a Book of the Month Club alternate selection, the publisher’s and the author’s enthusiasm was not matched by the book-buying public’s. Favorable reviews appeared in the Greensboro Record, Calgary Herald, and Martinez News-Gazette, while critical reviews appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer and Sydney Morning Herald, both praising the book’s ambition and themes but questioning aspects of characterization and narrative structure. The movie Return, which was released in 1985 to poor reviews, was loosely adapted from Harington’s novel.

Nevertheless, the book would eventually remake Harington’s life. In a story they both loved to tell, Harington’s future second wife, Kim, so fell in love with Diana’s story that she took the unusual step of writing a fan letter to the author. Kim’s boldness eventually opened the door for a run of new Stay More novels written over the last two decades of Harington’s life.

For additional information:

Butler, Jack. “An Appreciation.” Southern Quarterly 40 (Winter 2002): 142–143.

“Peter Straub Reads Donald Harington’s Some Other Place. The Right Place.” https://vimeo.com/25205890 (accessed February 20, 2025). [see Related Video in sidebar]

Walter, Brian, ed. Double Toil and Trouble: A New Novel and Short Stories by Donald Harington. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

———. The Guestroom Novelist: A Donald Harington Miscellany. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Brian Walter

St. Louis, Missouri

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Some Other Place. The Right Place.

Some Other Place. The Right Place.  Some Other Place. The Right Place.

Some Other Place. The Right Place.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.