calsfoundation@cals.org

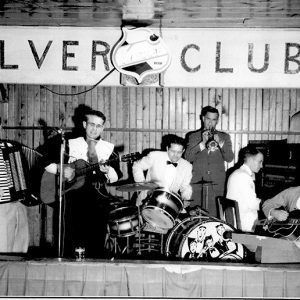

Silver Moon Club

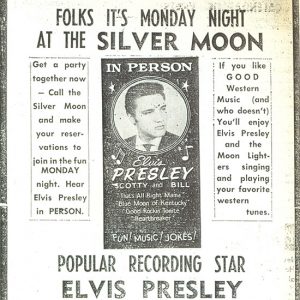

The Silver Moon was a popular nightclub and music venue in Newport (Jackson County). The club’s heyday was in the mid-1950s and early 1960s, when it hosted acts such as Glenn Miller, Bob Wills, Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Wanda Jackson, Conway Twitty, and Sonny Burgess, as well as African-American performers such as Louis Armstrong. At the time, the Silver Moon was the largest night club in Arkansas, holding 800–1,000 people on a busy night.

The Silver Moon was established in 1944 in the wake of Newport’s wartime economic boom. During the war, Newport constructed a large military base, the Newport Air Field, which doubled the town’s population. With so many servicemen in the area, local business owners sought to fulfill people’s desire for entertainment and recreation.

The original club was built by Bob Fortune, a well-known local gambler. According to Marvin Schwartz’s book We Wanna Boogie: The Rockabilly Roots of Sonny Burgess and the Pacers, the club initially brought in “wild-ass Marines and sailors from Memphis always looking for a fight.” For years, the Silver Moon maintained its reputation as the kind of place “respectable people,” especially women, did not visit. Fights were common. In 1955, Francis “Fats” Callis, a U.S. Navy veteran and a regular at the club, was shot on Christmas Day. The Silver Moon, nevertheless, attracted large crowds for years, drawing some of the best musical talent in the state and nation.

The club’s design was rudimentary. It was a long, rectangular, 7,200-square-foot dance hall with rock walls. Bare copper wire hung from the ceiling to conduct sound to the back of the club. In summer, it was infested with mosquitoes. The Silver Moon took advantage of its location, however, just to the north of Newport along U.S. Highway 67, away from the center of town and the prying eyes of police.

In the mid-1950s, Newport became a hotspot for the emerging rock and roll scene. At the time, the Silver Moon was owned by Don Washam, a veteran of World War II. In addition to having music, the club was a place where customers drank and gambled. Beer was sold, but customers had to bring in their own whiskey. It was said that any sixteen-year-old with a quarter could get a beer. Gambling took place in an invitation-only back room. Later, betting was moved to a room above the dance floor. The Silver Moon hosted African-American performers and integrated bands at times, but the clientele—in conformity to the era’s Jim Crow laws of racial segregation—was exclusively white.

Despite its raucous reputation, the Silver Moon had a dress code in the 1950s: dresses for women, coats and ties for men. Ownership was also careful not to alienate talent and paid musicians well. The club became a magnet for up-and-coming musicians. In 1955, Elvis Presley played there twice. But perhaps the most memorable shows were those by Sonny Burgess and the Pacers. Burgess liked the club so much that he named his original backing band the Moonlighters. His high-energy shows thrilled locals, establishing a name for himself and his band, who were best known as a live act.

The Silver Moon began its decline in the late 1960s. For years, local law enforcement had ignored the gambling happening inside the club, but that changed during the Winthrop Rockefeller administration. The governor made cracking down on gambling a priority—especially in Hot Springs (Garland County) but in Newport as well. Determined law enforcement shut down the Silver Moon for long periods at a time. By then, however, the days of attracting great musical acts had long passed. In the late 1960s, Washam sold the club for $55,000 to Abe Jones, a farmer and gambler. Sonny Burgess was asked to get involved on the business side of the club but refused.

The original Silver Moon burned in 1987. According to Schwartz’s book, visitors afterward found “a concrete foundation where the Silver Moon once stood and a rubble-filled ditch into which the remains of the burned club were bulldozed.” A new version of the Silver Moon, called the Silver Moon Banquet Hall, was built on the same lot as the original building. The club has little that resembles the original, but it honored the early history of the venue. In 2017, a service was held there for Sonny Burgess after his death.

The spirit of the original Silver Moon also lives on in Elvis’s hometown of Tupelo, Mississippi, where Charlie Watson Jr., whose father had owned the original club, opened a Silver Moon Club. (Watson, who played with the Pacers for a time, had moved to Tupelo with his parents when he was two years old.) By 2020, the club was called the Gardner-Watson Ice House/Silver Moon Club.

Former governor Mike Beebe, himself a musician who grew up in northeastern Arkansas, said there were “more legends about the Silver Moon than truth.” Although the history of the club has been not been studied or documented extensively, Henry Boyce, who runs the Highway 67 Museum in Newport, tried to remedy that. Before his death, Sonny Burgess reflected on what the Silver Moon might have been, such as a rock and roll museum, if it had not burned. At its height, though, Burgess said, “the Silver Moon was everything.”

For additional information:

Jacobson, Don. “The Rock ‘N’ Roll Highway Revisited.” Beachwood Reporter, March 15, 2009. http://www.beachwoodreporter.com/music/arkansas_rock_n_roll_highway.php (accessed November 20, 2020).

Morris, M. Scott. “Local Folks: Charlie Watson’s Tupelo Club Has Roots in Arkansas.” NEMS Daily Journal, February 4, 2013. https://www.djournal.com/news/local-folks-charlie-watson-apos-s-tupelo-club-has-roots/article_885dfb38-c51e-51b2-bc5f-8097cca37b95.html (accessed November 20, 2020).

Schwartz, Marvin. We Wanna Boogie: The Rockabilly Roots of Sonny Burgess and the Pacers. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2014.

Colin Woodward

Hampden-Sydney College

My bud J. J. and I first went in the Silver Moon Club when we were sixteen. No questions asked. Bought beer and had a great time.