calsfoundation@cals.org

Native Americans

Arkansas was home to Native Americans long before Europeans arrived. The first explorers met Indians whose ancestors had occupied the region for thousands of years. These were impressive and well-organized societies, to whom Europeans introduced new technologies, plants, animals, and diseases, setting in motion a process of population loss and cultural change that would continue for centuries. The United States government forced Indians to leave their ancient homelands and attempted—during the nineteenth century—to eradicate Indian traditions altogether. Indian communities persevered and today continue to celebrate their rich cultural heritage. This heritage is an important part of Arkansas history.

First Encounters

The first encounters between Europeans and Indians living in what is now Arkansas took place in 1541, when Hernando de Soto’s army camped on the eastern side of the Mississippi River. The Spaniards were visited on or about May 22 (on the Julian calendar) by Aquixo, the leader of a large community on the other side of the river. Aquixo arrived with a fleet of 200 canoes outfitted with banners and shields and filled with powerful teams of paddlers and painted warriors wearing colorful feathered regalia. The warriors were organized in ranks, and Aquixo was seated beneath a canopy erected over the stern of a very large canoe. He presented a gift of fish and plum loaves, but the Spaniards, alarmed at the size of Aquixo’s force, fired their crossbows and killed five or six Indians. So begins the history of relations between Europeans and Arkansas Indians.

When they crossed over to the western bank of the Mississippi, the Spaniards described the lands they observed as among the most agriculturally productive of any they had seen. Groves of nut and fruit trees and extensive fields of corn separated compact, fortified towns with populations numbering in the thousands. A system of roads and trails connected one town to the next. Many towns contained hundreds of square, thatch-covered houses. Open plazas provided space for public ceremonies. Flat-topped earthen mounds supported leaders’ residences and temples containing the remains of revered ancestors and finely crafted artifacts used in sacred ceremonies.

When the Spaniards reached the Arkansas River Valley, they encountered unfortified, dispersed villages composed of individual farmsteads—a pattern also observed in the Red River region of southwestern Arkansas. Like their counterparts in the Mississippi River Valley, these villages also were organized around ceremonial centers featuring the plazas, mounds, and temples that characterize sixteenth-century communities across the Southeast.

Sixteenth-century Indian societies had powerful leaders who traced their ancestry to legendary culture heroes, much like modern Americans tracing their lineages back to the “founding fathers” or to European nobility. Sometimes, leaders competed with one another to determine whose ancestor possessed the greatest power or prestige. When de Soto met with Pacaha and a rival leader, Casqui, Pacaha reportedly told Casqui that: “You know well that I am a greater lord than you, and of more honorable parents and grandparents, and that to me belongs a higher place.” But Casqui replied: “True it is that you are a greater lord that I, and that your forebears were greater than mine. But you know that I am older than you, and that I confine you in your walls whenever I wish, and you have never seen my country.”

In some parts of Arkansas, several communities were organized into larger “chiefdoms” under the command of an especially powerful leader. When the Spanish army entered the Red River valley, they suffered serious losses to a very well-organized fighting force consisting of warriors from three separate communities who were commanded by a paramount leader from the province of Naguatex.

Vibrant social and religious institutions acknowledged the role of powerful spiritual forces in day-to-day activities. Although Spanish chroniclers neglected to describe most Indian rituals, they did comment on the ceremonious receptions with which they were sometimes greeted as they approached Indian villages. In these ceremonies, community social organization was put on display as leaders and their close relatives marched out of their towns, heading orderly retinues of elders and nobles, warriors, and men, women, and children. Gifts of food and hides were offered as symbols of trust and mutual support. The Spanish failure to recognize these symbols became apparent as soon as they began seizing additional food supplies and enslaving Indian men, women, and children.

De Soto’s army spent more than two years in Arkansas, marching from one populous region to the next. The largest populations were concentrated in major river valleys. The Spaniards visited Tunica villages in the Arkansas River Valley and several Caddo communities in southwestern Arkansas, but most communities mentioned in the expedition accounts have names that do not correspond to the names of Indian groups identified by later explorers. Whether these name differences reflect translation problems or the presence of different groups during the different centuries cannot now be determined.

The results of de Soto’s expedition in Arkansas were catastrophic. The Spaniards brutally punished anyone resisting demands for food and services, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of Indians and many destroyed villages and agricultural fields. Though European explorers brought to American shores diseases to which Indians had no immunity, de Soto’s army probably did not carry active microbes as far as the Mississippi River. But their invasion coincided with a major drought period, so the seizure of native crops along with other depredations wreaked havoc across the land.

The Undocumented Era: 1543–1673

Following the departure of de Soto’s army in 1543, no further written accounts describing the Arkansas region were produced until the 1673 voyage of Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet down the Mississippi River. Seventeenth-century explorers entered a greatly altered landscape. Small villages replaced the sprawling towns described by de Soto’s chroniclers. Local leaders now commanded little authority beyond their own villages. Many communities apparently disappeared in the wake of de Soto’s destructive path.

Some groups identified by late-seventeenth-century explorers, such as the Siouan-speaking Quapaw and Osage, may have arrived in the region after de Soto’s departure, taking their place alongside indigenous groups including the Caddo and Tunica. The Tunica and possibly groups of Natchez Indians, who had earlier occupied portions of the Mississippi Valley north of the Arkansas River, were forced south in this shuffling of native communities. Some important ties with the past were still maintained. The remaining communities, though smaller and less complex than their predecessors, were organized according to the same rules of kinship and the same patterns of relationships connecting human communities with powerful spiritual forces.

Eighteenth-Century Lifeways

In contrast to the sixteenth-century communities that cannot readily be identified, the native communities observed by eighteenth-century English, French, and Spanish colonists represent groups that still exist. The Quapaw occupied the area surrounding the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers. Tunica villages (along with those of their linguistic relatives, the Koroa) were located farther south in the Mississippi Valley, in present-day Mississippi and Louisiana. Caddo villages were distributed throughout the Red and Ouachita river drainages in southwestern Arkansas and adjoining parts of Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas. Osage villages were located along the Missouri River and its tributaries, from which they extended into Arkansas on a seasonal basis.

All of these groups possessed religious beliefs that can be traced back to their pre-contact ancestors. Creation stories provide many details. One prominent theme expressed in these stories concerns the legendary accomplishments of ancient culture heroes who bequeathed to human communities the materials, practices, and guiding principles from which each community acquired its distinctive identity. Another theme concerns community responsibilities to maintain respectful relationships with inhabited lands, ancestors, and spiritual forces.

These beliefs were expressed in the social realm by individual statuses and roles. Adult men and women had duties and responsibilities contributing to overall community welfare. Labor was typically divided so that the women supervised agricultural activities while the men hunted and defended the community through warfare or by arranging political alliances. Religious leaders directed ceremonies to maintain favorable relationships between human and spiritual realms. Among the more important ceremonies were planting and hunting rituals, first-fruits ceremonies performed when crops ripened, and harvest ceremonies. Funeral ceremonies created and sustained spiritual ties connecting the living community to the lands in which their ancestors were buried.

Language and other cultural practices distinguished various groups. The Quapaw and Osage, who spoke Dhegihan dialects of the Siouan language family, lived in villages with distinctive forms of organization. In both groups, ancestry was traced through the father’s line, and each individual belonged to his or her father’s clan. Clans consisted of all living members of a person’s lineage, and because clans were responsible for the education and welfare of their members, they were often more important than an individual’s birth family. Quapaw and Osage clans (of which there were more than twenty in each tribe) were divided into two divisions called the Sky People and the Earth People. Sky People clans were responsible for the spiritual affairs of the community, while the Earth People clans were responsible for material affairs. Each clan performed specific rituals with the assistance of members from a counterpart clan from the opposite division. This practice supported a strong sense of solidarity, with each division depending upon the other to perform its sacred duties.

Quapaw and Osage Indians constructed bark-covered, pole-frame longhouses, each occupied by a group of related males and their families. Each family had its own section of the longhouse, and a row of hearths along the long axis of the dwelling marked individual family locations. Longhouses were arranged in clan neighborhoods. In Osage villages, longhouses associated with the two divisions were arranged on opposite sides of an east-west road that divided the community in half. Longhouses associated with the Sky People were built on the north (or “upper”) side of the road, whereas the Earth People longhouses were built on the south (or “lower”) side of the road, thus symbolizing relationships between the human and spiritual realms.

Caddo Indians, who spoke various Caddoan language dialects, traced their ancestry through the mother’s line. Clans were named after animals (Bison, Bear, Panther, Wolf, and Beaver clan names are known from historical sources) and were ranked relative to the animal’s strength. Children belonged to their mother’s clan unless the father belonged to a “stronger” clan, in which case the man’s sons belonged to his clan. This principle of relative strength was also used to organize relationships among community leaders. The village leader, called the caddi, inherited his office through a succession of males from “strong” lineages and was ranked above other leaders who served as his lieutenants. Ranked above the caddi was a high priest called the xinesi, who was in charge of rituals that maintained relations with the spirit world. The xinesi’s counterpart in the spirit realm was Ayo-Caddi-Aymay, the supreme being who, in turn, was served by lesser deities.

Caddo houses—tall, circular structures covered from bottom to top with bundles of grass thatch—were often forty to sixty feet in diameter, large enough to hold several families related through the female line. Domestic activities performed around the central hearth were supervised by the senior woman of the household. Each family occupied a space along the interior perimeter separated by benches and dividers covered with woven mats. Each household maintained its own crop fields and woodlots, so Caddo communities were, in fact, dispersed collections of neighboring farmsteads that stretched sometimes for miles along one or both sides of a river. The caddi’s farmstead was located at or near the community’s center, symbolizing the concept of a central locus of power.

The sacred fire temple usually was located at the edge of the community where the main road entered. This location marked the community’s gateway, where visiting dignitaries were typically escorted to the fire temple for welcoming ceremonies. The fire temple was also the place where the xinesi performed rituals that brought community affairs to the attention of spirit beings. The location of the fire temple at the community’s edge represented another central place—a “gateway”—at the invisible boundary between the human and spirit realms. As with Osage and Quapaw settlement patterns, the spatial plan of Caddo communities thus represents essential features of social organization and religious beliefs.

Less is known about eighteenth-century Tunica culture. Leaders inherited their offices, and separate categories of leaders were responsible for internal versus external affairs. The Tunica division of labor was unusual among Southeastern Indians: men rather than women were in charge of agricultural activities. The sacred fire, as well, represented a female, rather than a male, solar deity. Tunica houses had circular floor plans and clay-plastered walls surmounted by pitched, grass-thatched roofs. How the residences were arranged remains unknown, but village configurations included open plazas and temple mounds.

One other characteristic shared by eighteenth-century Arkansas Indians was their use of the calumet ceremony to greet European visitors. The calumet was a two-piece implement made of a carved stone tobacco pipe attached to a long wooden stem decorated with symbols representing the community’s major divisions. Participants smoked the calumet to create an alliance in which social rights and obligations were extended to visitors, in effect making them kin. The fragrant smoke rising from the pipe and disappearing into the air carried this relationship into the spirit realm. Variations in calumet rituals corresponded to social differences among various Indian groups. Osage and Quapaw calumet ceremonies, for example, involved the participation of all community members and visitors, in keeping with the inclusive nature of their social organization. In contrast, the Caddo performed a different version of the ceremony in which only the leaders of the allied groups participated, since leaders represented the other members of their respective communities. In sum, the calumet ceremony served to frame Indian-European relationships within native kinship categories and religious beliefs.

Colonial Impact

Permanent French colonies in Arkansas, established first at Arkansas Post and later at other locations along the Arkansas, Red, and Ouachita rivers, introduced new social, economic, and political arrangements. A good example of these new arrangements is seen in the emergence of what historians have called a frontier exchange economy. The key features of this new economy include the Indian production of goods required by colonists and the exchange of those goods for European manufactured items through a system of face-to-face bartering between Indians and traders. In a barter system, exchanges are negotiated using a generally accepted set of values—for example, thirty gunflints or fifty musket balls for one dressed deerskin.

In Louisiana Territory (to which Arkansas belonged during the eighteenth century), the key Indian commodities in the frontier exchange economy were horses, hides, meat (smoked and dried deer and buffalo), tallow and oil (rendered mainly from bear fat), and agricultural produce. Indians exchanged these goods for firearms and ammunition; cloth and clothing; metal tools and implements; and sundry items including beads, bells, combs, and mirrors. The importance of Indian commodities within colonial economies was such that European officials offered incentives in the form of annual gifts of trade goods. Over time, Indians came to depend upon these goods.

Involvement in the frontier exchange economy also brought a significant increase in the time and effort Indian men devoted to hunting, with corresponding increases in the time and effort Indian women devoted to agricultural activities and the processing of hides and other animal products. Contests for control of hunting territories also pitted many Indian communities against one another, as groups were forced to relocate villages to expand the range of their hunting operations and gain closer access to trading posts. These conflicts produced a need for skilled diplomats able to smooth differences among various Indian groups and between Indian communities and European officials. Throughout the eighteenth century, many Caddo leaders, such as Tinhiöuen, Bigotes, and Dehahuit, rose to these challenges and became well known for their abilities to apply principles of Caddo leadership to resolving international conflicts.

Many traders moved into Indian communities and often married Indian women in order to expand their economic partnerships. Indian communities considered these arrangements beneficial to their goals of gaining increased access to trade goods. Closer contact with Europeans also brought epidemic diseases and sometimes drew Indian villages into larger colonial affairs. In 1756, the French governor of Louisiana, Louis de Kerlérec, ordered the arrest of four deserters who sought refuge among the Quapaw. When Kerlérec demanded release of the deserters, the Quapaw leader Guedetonguay replied that, by seeking refuge in the Quapaw’s sacred temple, the men were, by custom, absolved of their crimes. Guedetonguay further argued that the Quapaw had sacrificed much in supporting Louisiana’s military efforts against the English-allied Chickasaw and, therefore, expected consideration in return. Kerlérec was forced to concede to Guedetonguay’s demands in order to maintain the spirit of trust and mutual support that provided the basis for Indian alliances, on which the security of French Louisiana depended.

The Nineteenth Century

Relationships between Indians and their European allies changed dramatically when Arkansas became part of the United States following the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. In the decades that followed, population growth east of the Mississippi River led to increased pressures to open new lands for white American settlement. Consequently, the U.S. government removed communities of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole to less densely populated regions west of the Mississippi River. For Arkansas Indians, this brought an increased number of immigrants—both Indian and non-Indian—into their territories. Some of these immigrants, the Cherokee in particular, found temporary refuge in Arkansas. But when federal and newly formed state governments (including Arkansas’s) sought to open additional lands for white American settlement, Indians across the Southeast lost their status as allies and were viewed instead as troublesome vagabonds to be removed even farther west, to a newly created Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma and Kansas.

Accordingly, the United States imposed a series of treaties, enacted between 1808 and 1835, forcing the Caddo, Osage, and Quapaw to relinquish their Arkansas lands. In 1825, the Osage were placed on a reservation in Kansas, where for several years they worked to maintain a traditional way of life. In 1824, the Quapaw were relocated to Caddo lands along the Red River in present-day Louisiana, where they lost crops to floods over successive planting seasons. Some returned to the Arkansas River while others attempted to persevere in the Red River settlement. The Arkansas River group in 1833 joined a group of Creek (Muscogee) in the Indian Territory. In 1834, the Red River group, after a brief return to the Arkansas River, were removed by Indian agent Wharton Rector to an Indian Territory reservation along the Neosho River. There, the Quapaw cleared land, planted crops, and built homes before it was discovered that Rector had led them to the wrong location. The Quapaw were ordered to abandon their settlements and start anew at a different location.

The Caddo also experienced difficulties as increasing numbers of Alabama, Cherokee, Choctaw, Coushatta, Delaware, Osage, Shawnee, and white settlers invaded their lands. Under pressure from U.S. Indian agents, the Caddo sold their Arkansas lands in 1835 with the intention of moving to Texas. The revolution for Texas independence from Mexico delayed this move until 1840, when the Caddo relocated to sites along the Upper Trinity and Brazos rivers. Attacks from ruthless white Texans prompted additional moves, until the Caddo were placed, in 1855, on a reservation along the Brazos River fifteen miles downstream from Fort Belknap. Caddo efforts to develop a stable agricultural economy brought no decrease of attacks from white settlers, so in 1859, U.S. Army troops escorted them to yet another location, this time along the Washita River in present Caddo County, Oklahoma, where they shared a reservation with many other Indian groups.

The first Cherokee settlements in Arkansas at the end of the eighteenth century were along the St. Francis, Arkansas, and White rivers. Additional Cherokee settlements were established in the first decade of the nineteenth century along the Arkansas River in the vicinity of modern-day Russellville (Pope County). In 1817, these “Western” Cherokees signed a treaty with the United States that established a large reservation between the Arkansas and White rivers. By this point in their history, the Cherokee practiced a rural agricultural lifestyle that differed little, at least in outward appearances, from that of their white neighbors. Nonetheless, strong leaders who embraced traditional values, such as Duwali, Takatoka, and Tahlonteskee, rose to positions of power and authority. Tahlonteskee in 1818 petitioned the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to send missionaries to the Arkansas settlements. Two years later, Tahlonteskee’s brother, John Jolly, played a key role in establishing Dwight Mission along Illinois Bayou. It served for eight years both as a mission and a school. In 1828, the Arkansas Cherokee were forced to sell their lands and move their community, along with Dwight Mission, to a new location farther up the Arkansas River in Indian Territory.

Within a decade, many Eastern Cherokee joined their Western relatives as the U.S. Army forcibly removed thousands of Southeastern Indians to Indian Territory from homelands east of the Mississippi River via overland and riverine routes that came to be known as the Trail of Tears. As a result of these removals, Indian communities suffered population losses to disease, economic disasters when crops succumbed to summer droughts, attacks from neighboring white settlers, and incompetence and even treachery at the hands of U.S. Indian agents.

The outbreak of the Civil War brought more disruption and displacement. In the spring of 1861, Union troops retreated from Indian Territory to Kansas as Confederate troops entered the region from the south. In an effort to solidify relations with the Indians, President Jefferson Davis appointed General Albert Pike from Arkansas to serve as commissioner to the Indian Territory tribes. Pike succeeded in organizing a Confederate Indian army consisting largely of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole, whose own slave-owning history aligned them with the Southern cause. Under the command of Cherokee general Stand Watie, Indian troops played an important role in disrupting Union movements along the Arkansas River between Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Fort Smith (Sebastian County).

Pike also succeeded in establishing treaties with other tribes, in which the Confederate states pledged to provide material support and protection in exchange for the Indians’ allegiance. Given the abandonment of Indian Territory by Union forces, the Indians had no choice but to accept Pike’s offers. During the first years of the war, several Osage bands fought on the side of the Confederacy, even as some of their relatives joined Union forces. When Confederate promises of support and protection failed to materialize, many Indian Territory tribes, including the Caddo, Osage, and Quapaw, fled to Kansas where Union forces provided nominal protection and support. At the war’s end, these groups returned to their former Indian Territory settlements, only to find them devastated from the effects of the war. Adding insult to injury, U.S. Indian agents imposed harsh penalties in retaliation for their alliances with the Confederacy, including reduction of annual support payments and forfeitures of reservation lands. During the Fort Smith Conference of 1865, for example, the federal government listed seven stipulations with which the tribes must comply in order to reestablish proper relations with authorities of the United States, including the surrender of lands in Kansas to which many had fled during the war.

The desperate circumstances that gripped Indian Territory in the late nineteenth century convinced the federal government that more assertive measures were required to improve Indian lives. Accordingly, Congress in 1887 passed the Dawes Act, otherwise known as the Indian Allotment Act, under which reservation lands were subdivided into parcels (generally 160 acres) that were allotted to individual families. Remaining parcels were publicly sold. Despite the good intentions behind it, the Dawes Act broke up large Indian landholdings, thereby bringing to an end the multi-family networks of cooperation and sharing that up to this point comprised the social fabric of Indian communities.

Federal policies enacted from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century were designed to eradicate Indian cultural practices. Native languages, social systems, political institutions, religious beliefs, and even clothing and hairstyles all came under assault. This was the era during which Indian children were sent away to boarding schools, and mission organizations increased their efforts to convert Indians to mainstream Protestant and Catholic religions.

Twentieth-Century Developments

In 1934, the United States government reversed its assimilation policy by passing the Indian Reorganization Act, which restored native rights and promoted Indian self-determination. The Caddo and Quapaw adopted new constitutions and organized new governing councils in the years following the passage of this act. The Osage and Cherokee revised constitutions and governing bodies they had previously created. The Tunica eventually joined the Biloxi and, in 1976, incorporated as the Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe of Louisiana.

These new governments created some challenges as traditional political institutions based on descent within clan and lineage systems were transformed into new systems in which individuals were elected to political office. In time, most of the difficulties were ironed out, and elected tribal governments set about creating new economic opportunities with the support of federal and state assistance. New economic ventures, including gaming, tax-free tobacco sales, and other business ventures located on Indian lands provided additional support for student and adult educational programs, assistance programs for the elderly, health care programs, and cultural resource management and preservation programs. Because most Caddo, Osage, and Quapaw living in Oklahoma and the Tunica-Biloxi living in Louisiana are located in rural areas with low population densities and limited economic opportunities, the governing councils of these nations continue to face many financial difficulties, most of which are related to trends within the wider national economy.

Economic and social developments made possible by the Indian Reorganization Act, coupled with other federal legislation including the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, produced a resurgence of cultural activities in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—many with roots extending far back into the past. Especially important are modern stories, songs, dances, ceremonies, and religious observations that celebrate origins, historical events, and time-honored values and principles.

Passage of the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990 provided mechanisms for Indian tribes to reclaim artifacts and skeletal remains housed in museums and other federally funded institutions. Several museums have repatriated ancestral skeletal remains and funerary items to Arkansas tribes, some of which have been reburied in protected cemeteries located in Arkansas. The ceremonies performed in connection with these reburials have restored spiritual ties to the land that were severed during the removal era. Other repatriated items have been transferred to Indian custody for use in traditional ceremonies and tribal education programs. In 1991, the Quapaw gathered in Arkansas to celebrate the designation of the Menard-Hodges Site as a National Historic Landmark—archaeologists believe this is the Quapaw village of Osotuoy near which Henri de Tonti established the first Arkansas Post in 1686. Other archaeological properties in Arkansas have been designated as sacred sites under President Clinton’s 1996 Executive Order 13007 (“Accommodation of Sacred Sites”). Through these activities, modern Caddo, Cherokee, Osage, Quapaw, and Tunica are beginning to reclaim their ancestral ties to Arkansas.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaws and Old World Newcomers, 1673–1804. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Clayton, Lawrence A.,Vernon James Knight, Jr., and Edward C. Moore, eds. The De Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto in North America in 1539–1543. 2 vols. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Duncan, David Ewing. Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

DuVal, Kathleen. The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Galloway, Patricia, ed. The Hernando de Soto Expedition: History, Historiography, and “Discovery” in the Southeast. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Hoffman, Michael P. “Protohistoric Tunican Indians in Arkansas.” In Cultural Encounters in the Early South, edited by Jeannie M. Whayne. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Hudson, Charles. Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

———. The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976.

Jeter, Marvin D. “From Prehistory to Ethnohistory in and near the Northern Lower Mississippi Valley.” In The Transformation of the Southeastern Indians, 1540–1760, edited by Robbie Ethridge and Charles Hudson. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2002.

Sabo, George, III. “Dancing into the Past: Colonial Legacies in Modern Caddo Indian Ceremony.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62 (Winter 2003): 423–445.

———. Paths of Our Children: Historic Indians of Arkansas. Rev. ed. Popular Series No. 3. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2001.

———. “Rituals of Encounter: Interpreting Native American Views of European Explorers.” In Cultural Encounters in the Early South, edited by Jeannie M. Whayne. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Schambach, Frank F. “Spiro and the Tunica: A New Interpretation of the Role of the Tunica in the Culture History of the Southeast and the Southern Plains, A.D. 1100–1750.” In Arkansas Archaeology: Essays in Honor of Dan and Phyllis Morse, edited by Robert C. Mainfort Jr. and Marvin D. Jeter. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Scott, Robert J. “Investigating the Causes and Consequences of Depopulation in Southeast Arkansas, A.D. 1500–1700.” PhD diss., Southern Illinois University, 2019.

Usner, Daniel H., Jr. Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Mississippi Valley before 1783. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

West, Cane W. “Learning the Land: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Southern Borderlands, 1500–1850.” PhD diss., University of South Carolina, 2019.

Whayne, Jeannie M., Thomas A. DeBlack, George Sabo III, Morris S. Arnold, eds. Arkansas: A Narrative History. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2013.

Young, Gloria A., and Michael P. Hoffman, eds. The Expedition of Hernando de Soto West of the Mississippi, 1541–1543. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

George Sabo III

Arkansas Archeological Survey

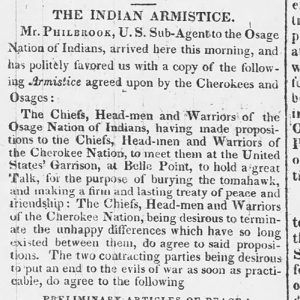

Armistice Story

Armistice Story  Caddo Dancers

Caddo Dancers  Caddo Drum

Caddo Drum  Caddo Hair Ornaments

Caddo Hair Ornaments  Caddo Honor Guard

Caddo Honor Guard  Choctaw Nation Border Marker

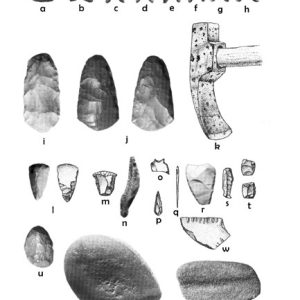

Choctaw Nation Border Marker  Dalton Period Artifacts

Dalton Period Artifacts  Duwali

Duwali  Pompey Factor

Pompey Factor  Jo Hart

Jo Hart  Head Pot

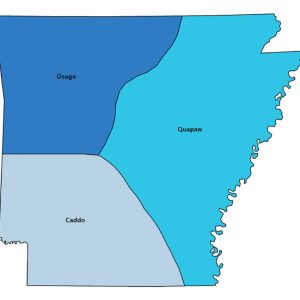

Head Pot  Indian Extents Map

Indian Extents Map  Menard-Hodges Primary Mound

Menard-Hodges Primary Mound  Native American Emigration Story

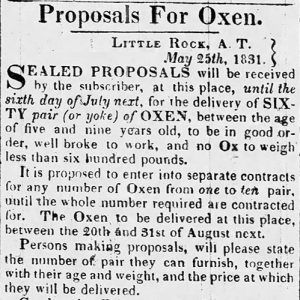

Native American Emigration Story  Native American Supplies Ad

Native American Supplies Ad  Native American Treaty Story

Native American Treaty Story  Old Independence Regional Museum Exhibit

Old Independence Regional Museum Exhibit  Quapaw Tribe Visiting Site

Quapaw Tribe Visiting Site  Sarasin's Tombstone

Sarasin's Tombstone  Sequoyah

Sequoyah  Sequoyah Center Stacks

Sequoyah Center Stacks  Test Excavations

Test Excavations  Stand Watie

Stand Watie

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.