calsfoundation@cals.org

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

aka: NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded on February 12, 1909, and is America’s oldest civil rights organization. The first local branch in Arkansas was established in Little Rock (Pulaski County) on July 4, 1918. The president was John Hamilton McConico, and the fifty founding members included many of the city’s leading African-American figures of the time, including Joseph Albert Booker, Aldridge E. Bush, Chester E. Bush, George William Stanley Ish, Isaac Taylor Gillam, and John Marshall Robinson. The state was the site of one of the national organization’s early court triumphs: In the case of Moore v. Dempsey (1923), NAACP lawyers won a reprieve from the death penalty for six African-American men on the grounds of improper influence by a hostile courtroom. The men had been among the twelve who were convicted for their alleged role in the Elaine Massacre and sentenced to death.

Despite this victory, the NAACP experienced slow growth in the state. By 1940, there were only six local branches. However, World War II changed the fortunes of the NAACP both nationally and in Arkansas. A wartime upsurge in black activism saw NAACP national membership grow tenfold from 50,000 to 500,000 members between 1940 and 1946.

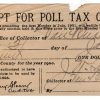

Young Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) attorney William Harold Flowers sought to address the lack of black activism in Arkansas in 1940 by founding the Committee on Negro Organizations (CNO). Echoing the activities of the NAACP, Flowers looked to build a base for civil rights by running voter registration drives. His efforts helped raise the number of registered black voters in Arkansas from 4,000 to 47,000 between 1940 and 1947.

The burst of activism led to other developments. In 1942, a member of the Little Rock Classroom Teachers’ Association (CTA), Sue Morris, sued for the equalization of black teachers’ salaries with the salaries of the city’s white teachers. The case attracted help from the national office of the NAACP and brought NAACP Legal Defense Fund director-counsel Thurgood Marshall to the city. The NAACP fought the case to a successful conclusion on appeal in 1945.

The teachers’ salary suit led to the NAACP’s expansion in the state. In 1945, an NAACP Arkansas State Conference of branches (ASC) was established. From the outset, the ASC was wracked with disagreements. More conservative members, such as ASC president the Reverend Marcus Taylor of Little Rock, viewed their role as simply to collect membership dues. More militant figures such as Flowers, who was appointed ASC chief recruitment officer, wanted the organization to play a more active role in the state.

A showdown came in 1948 when Flowers ousted Taylor as ASC president. Though the NAACP’s national office was not completely happy with this, it was resigned to Flowers’s leadership. As Donald Jones, NAACP regional secretary, reported: “Largely responsible for the fine NAACP consciousness in Pine Bluff and the growing consciousness in the state is Attorney Flowers whose…tremendous energy ha[s] made him the state’s acknowledged leader.”

Flowers’s election gave heart to other local activists. In 1948, the co-owner of Little Rock’s Arkansas State Press newspaper, Daisy Bates, filed an application to form a countywide “Pulaski County Chapter of the NAACP” in an attempt to undercut the authority of conservative leaders in the Little Rock NAACP branch. NAACP director of branches Gloster B. Current turned down Bates’s application and told her to join the Little Rock branch instead.

More conflict arose in 1949 when Flowers was asked by the national office to resign as president because of allegations of financial impropriety. Though he vehemently contested these claims, Flowers stepped aside to avoid outright mutiny in the state. Some members threatened to withdraw the ASC from the control of the national organization altogether. Flowers was replaced as ASC president by Dr. J. A. White. When White fell ill and resigned from office in 1951, W. L. Jarrett, a veteran of early CNO campaigns, acted as a temporary replacement.

In 1952, activist members of the NAACP again triumphed when Daisy Bates was elected ASC president. An exasperated Ulysses Simpson Tate, NAACP southwest regional attorney, reported: “I am not certain that she was the proper person to be elected [but] there was no one else…who offered any promise of doing anything to further the work of the NAACP in Arkansas.”

Bates’s election coincided with a fateful phase of the NAACP’s history in the state. On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which decreed an end to segregated schools. The NAACP led the struggle to implement Brown in Arkansas. When efforts to persuade Little Rock school superintendent Virgil T. Blossom to proceed with school desegregation in a transparent and timely manner failed, the local Little Rock NAACP branch filed suit in Aaron v. Cooper (1956). The courts subsequently upheld the limited plan for desegregation drawn up by Blossom.

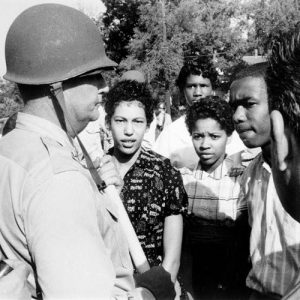

In September 1957, the struggle over school desegregation culminated in the Little Rock desegregation crisis. Daisy Bates, along with her husband, L. C. Bates, played an important role in looking after the interests of the nine students (who came to be known as the Little Rock Nine) who desegregated Central High School. The Bateses suffered a number of attacks on their home by segregationists. An advertising boycott put the Arkansas State Press out of business in 1959. State Attorney General Bruce Bennett pressed Daisy Bates to release NAACP membership details, which she refused to do.

On September 12, 1958, the NAACP successfully argued the landmark ruling of Cooper v. Aaron (1958) before the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that violence and disruption could not be used as excuses to delay school desegregation. Governor Orval Faubus then closed all of Little Rock’s schools to prevent integration. In a referendum, Little Rock voters backed his school-closing plan, and schools remained closed in the 1958–59 academic year, known as the Lost Year. In May 1959, members of the white community mobilized to remove segregationist school board members. Schools reopened on a token desegregated basis in August 1959.

Daisy Bates spent much of her time after the school crisis writing a memoir in New York City. In 1961, Pine Bluff attorney George Howard succeeded her as ASC president. In 1965, Howard was succeeded by North Little Rock (Pulaski County) dentist Dr. Jerry Jewell. Jewell bemoaned the lack of NAACP activity in the state. New civil rights groups, such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), now competed for attention and resources. Jewell believed that L. C. Bates, who worked as a state field secretary for the NAACP in the 1960s, was not active enough in recruitment efforts. When the national office retired Bates against his wishes in May 1971, it brought an end to the influence of the Bateses in the state organization and the most high-profile years of the NAACP in Arkansas.

Like its parent national organization, the NAACP in Arkansas has continued to play an important, though less dominant, role in African-American civil rights since the 1960s. In keeping with its past activities, the current mission statement of the ASC reads: “The NAACP ensures the political, educational, social and economic equality of minority groups and citizens; achieves equality of rights and eliminates race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; removes all barriers of racial discrimination through the democratic processes; seeks to enact and enforce federal, state, and local laws securing civil rights; informs the public on the adverse effects of racial discrimination and seeks its elimination; educates persons as to their constitutional rights and to take lawful action in furtherance of these principles.” The ASC president is Dale Charles, who is also president of the Little Rock NAACP branch.

A number of institutions of higher learning in Arkansas have chapters of the NAACP. In 2015, the chapter at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR), which had been dormant, became active again as part of a partnership with the UALR Institute on Race and Ethnicity.

For additional information:

“The Little Rock Crisis: A Fiftieth Anniversary Retrospective.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Summer 2007).

Anderson, Karen. “The Little Rock School Desegregation Crisis: Moderation and Social Conflict.” Journal of Southern History 70 (August 2004): 603–636.

———. Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Arkansas State Conference, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. http://www.arnaacp.org/ (accessed February 14, 2022).

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock.Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown: University of Connecticut Press, 1988.

Freyer, Tony. The Little Rock Crisis: A Constitutional Interpretation. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984.

———. Little Rock on Trial: Cooper v. Aaron and School Desegregation. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007.

Jacoway, Elizabeth. Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis That Shocked the Nation. New York: Free Press, 2007.

Kilpatrick, Judith. There When We Needed Him: Wiley Austin Branton, Civil Rights Warrior. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

Kirk, John A. “Arkansas, the Brown Decision and the 1957 Little Rock School Crisis.” In Understanding the Little Rock Crisis: An Exercise in Remembrance and Reconciliation, edited by Elizabeth Jacoway and C. Fred Williams. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

———. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. “Daisy Bates, the NAACP and the Little Rock School Crisis: A Gendered Perspective.” In Gender in the Civil Rights Movement, edited by Peter Ling and Sharon Monteith. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

———. “‘He Founded a Movement’: W. H. Flowers, the Committee on Negro Organizations and Black Activism in Arkansas, 1940–1957.” In The Making of Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement in America, edited by Brian Ward and Tony Badger. London: Macmillan, 1996.

———. “The Little Rock Crisis and Postwar Black Activism in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Autumn 1997): 273–293.

———. “Massive Resistance and Minimum Compliance: The Origins of the 1957 Little Rock School Crisis and the Failure of School Desegregation in the South.” In Massive Resistance: Southern Opposition to the Second Reconstruction, edited by Clive Webb. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

———. “The NAACP Teachers’ Salary Equalization Campaign: African American Women Educators and the Early Civil Rights Struggle.” Journal of African American History 94 (Fall 2009): 529–552.

———. “‘They Say…New York is Not Worth a D—n to Them’: The NAACP in Arkansas, 1918–1971.” In Long is the Way and Hard: One Hundred Years of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, edited by Kevern Verney and Lee Sartain. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Kirk, John A., ed. An Epitaph for Little Rock: A Fiftieth Anniversary Retrospective on the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Lewis, Catherine M., and J. Richard Lewis, eds. Race, Politics and Memory: A Documentary History of the Little Rock School Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

Smith, C. Calvin. War and Wartime Changes: The Transformation of Arkansas, 1940–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Stockley, Grif. Daisy Bates: Civil Rights Crusader from Arkansas. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2005.

———. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

John A. Kirk

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

The July 31August 1, 1953 Arkansas State Conference of the NAACP convened in Newport, Arkansas. The newspaper reported that it was “one of the most successful two-day sessions in the history of the conference.” It was probably a first for this small town. This occurred about nine months before the Brown v. Board of Education decision (May 17, 1954) and seventy or more days before the Supreme Court’s scheduled re-argument of the case (October 12, 1953). This was a focal point for the event. In attendance were several outstanding NAACP officials including Daisy Bates, Gloster Current, U. Simpson Tate, Wiley Branton Sr., W. Harold Flowers, and Thad D. Williams. Ozell Sutton was the state’s youth director during this time. My father, Laurence Von (L. V.) Roddy, who was the Newport chapter’s president and 3rd state vice president, and Rev. J. Edward Tillman, pastor, St. Paul AME Church, hosted the conference. The NAACP delegation of officials visited Newport mayor J. N. Hout’s home. Note that this was a segregated town. Mayor Hout was to have been one of the speakers at the two-day conference; however, he notified the leaders that he was ill and his physician had confined him to bed. Well, the leaders did a house call and delivered many “get well” wishes. They did not enter through the back door; the report states that they were “warmly and sincerely” received as guests. This particular act did not fit the general public’s perceived image of segregation in the South during the 50s. I have some memory of the event and the excitement surrounding it. Being honest, as a seven year old, I especially looked forward to a big serving of lime frappé, which was prepared by my mother and other local women.