calsfoundation@cals.org

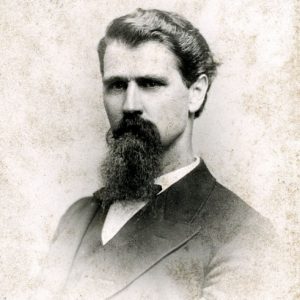

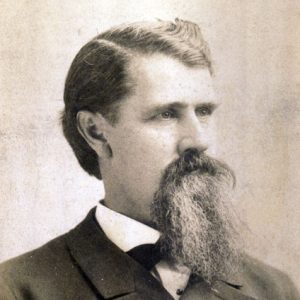

James Henderson Berry (1841–1913)

Fourteenth Governor (1883–1885)

James Henderson Berry served as a Civil War officer, lawyer, Arkansas legislator, speaker of the Arkansas House of Representatives, and circuit judge for the Fourth Judicial District before being elected Arkansas’s fourteenth governor. A staunch Democrat, he was governor for two years and promoted increased taxation for railroads, repudiation of state debt, equal protection for all citizens, reform of the state penal system, and economy in government. Berry followed his stint as governor with twenty-two years of service as a United States senator, from 1885 to 1907.

Berry was born in Jackson County, Alabama, on May 15, 1841. His parents, James M. and Isabelle (Orr) Berry, were farmers, and ten of their children lived to adulthood: Granville, Mary, Fannie, Dick, James, Arkansas, Willie, Sophrona, Albert, and Emma.

In 1848, his family moved to Arkansas, settling on a farm near Carrollton (Carroll County), where Berry’s father opened a store. Berry “learned to read and write a little, and something of arithmetic” during occasional school sessions, but mostly he helped on the farm. When Berry was seventeen, his father enrolled him in the Berryville Academy. Ten months later, his mother died, and Berry’s father sold the farm. Berry went to Yellville (Marion County) to work in the store of a cousin also named James H. Berry.

Berry returned to Carrollton on September 19, 1861, to join the Confederate army. Fellow soldiers elected him second lieutenant of Company E, Sixteenth Arkansas Infantry. They fought in the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862 under General Earl Van Dorn and lost. His unit retreated to the Arkansas River, downriver to Memphis, and then to Corinth, Mississippi. There, they joined General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard’s army, fought a skirmish at Corinth in mid-April 1862, and retreated to Tupelo, Mississippi. Berry rejoined General Van Dorn and fought at the battles of Iuka and Corinth in Mississippi. On October 4, 1862, during the Battle of Corinth, he lost his right leg above the knee. He was captured by the Union Army, recuperated in the hospital at Iuka, was eventually paroled, and returned home to Arkansas.

Berry’s wartime experiences deeply affected his outlook and activities. It is not clear why he joined the Confederate army, though probably, as a resident of the Ozarks, he was focused more on personal freedom and the rights of states to govern themselves than on slavery. He was proud of his service to the Confederacy. Until his death nearly fifty years later, he retained close ties to his fellow veterans and spoke at many Confederate gatherings and reunions.

After the war, Berry taught school for a while in Ozark (Franklin County). There he met and married Lizzie Quaile, daughter of prominent businessman James F. Quaile. In his autobiography, Berry reflects that Quaile “was unwilling for his daughter to marry me because I had no means of support and no prospects.” Berry’s remarks give a measure of his integrity: “I had absolutely nothing, not even a law license, and was on crutches. When I had daughters of my own I realized that under the same conditions and circumstances, I would have done as he did.” The two men did not speak for seventeen years. Berry’s nomination as governor apparently allowed Quaile to put aside his concerns, and they remained on good terms thereafter.

The young couple moved to Carrollton, where he taught school and studied the law. In 1866, Berry won a seat in the Arkansas House of Representatives on the Democratic-Conservative ticket. He passed the Arkansas Bar on his way to Little Rock (Pulaski County) for his first session. In 1869, Berry moved his family to Bentonville (Benton County) and opened a law practice with his brother-in-law, Colonel Sam W. Peel. They worked together successfully for five years, and later both served in the U.S. Congress.

Berry was elected to the Arkansas General Assembly from Benton County in 1872. During 1874, the Brooks-Baxter War was the focus of Arkansas politics. This conflict, contesting the governorship of the state, led Governor Elisha Baxter to call an extraordinary session of the legislature. A loyal Democrat and backer of Governor Elisha Baxter, Berry led the effort to replace the absent Republican speaker of the house, one Mr. Tankersley, with a Democrat. Tankersley was a Brooks supporter. Berry was selected speaker of the house, and he guided the legislature into calling a constitutional convention. This essentially marked the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas and the beginning of nearly a century of Democratic Party dominance.

At the end of his term, Berry returned to Bentonville and entered private law practice with Judge R. W. Ellis, whom he fondly remembered as “one of the most lovable men I ever knew, always good natured and good humored, always especially considerate of the other man.” Under Ellis’s mentorship, Berry refined his knowledge of the law and the courts. In 1878, he was elected judge of the Fourth Judicial District, which covered eight counties. Berry was efficient, and his decisions were rarely reversed by higher courts. He commented in his autobiography, “[T]he four years that I served as judge of the court were the most pleasant of all my public life and I frequently afterward regretted that I had not remained on the bench.”

Berry resigned as judge in 1882 to run as the Democratic candidate for governor against Republican W. D. Slack. The white voters of Arkansas were tired of Radical Reconstruction, engineered by Republicans, and Berry won by a wide margin. He took office on January 13, 1883.

Berry’s legislative agenda included raising taxes on the railroads and passing the Fishback Amendment, which refused the payment of some questionable state bonds. He also sought a review of state officers accused of mishandling their accounts, and he wanted to cut costs by holding both federal and state elections on the same day. His efforts returned mixed results. The legislators created a railroad commission and imposed modest taxes, but they exempted several kinds of railroad property from taxation. The Fishback Amendment made it to the general ballot in 1884, passed by a wide margin, and repudiated, or voided, a portion of the state’s bonded debt. An unintended consequence of this was a bad credit rating that haunted the state for decades. As for the matter of state officers and their accounts, only a few ever reimbursed the state. Finally, the legislature turned down Berry’s request to combine elections, as doing so would have prevented Democrats from using questionable methods to influence the local vote.

Berry’s social agenda was to seek equal justice for all citizens, whatever their race or color. His methods were indirect and paternalistic. He felt that progress for the African Americans of the state would come, eventually, through education and economic progress, not through political activism. His efforts were limited to ensuring that legal process and not mob rule dealt with lawbreakers, black or white. For example, in the summer of 1883, he sent in the militia to Howard County to stop a white mob from lynching a group of African Americans who had killed an alleged white rapist.

Berry also despised the state prison system, calling the convict-lease system “uncivilized, inhumane, and wrong.” Though he advocated prison reform, he could not persuade the legislature to fund a system to work convicts under state supervision. It was simply more economical to lease convicts out to private contractors who paid for their use. He did, however, support a plan to improve the Arkansas Nervous Hospital.

Berry chose not to run for a second term in 1884. His decision, in part, came down to finances. As governor, his expenses exceeded his salary. Also, he had decided to run for the U.S. Senate. In 1885, senators were chosen by state legislatures, not by direct election. Berry failed in his first senate attempt, but a few months later Senator Augustus Hill Garland accepted a cabinet position as attorney general in President Grover Cleveland’s administration. The Arkansas state legislature chose Berry to take Garland’s place on March 25, 1885. He remained in that office until 1907.

As senator, Berry worked diligently in the background, supporting the Democratic Party and promoting the interests of Arkansas. He served on the Rivers and Harbors, Public Lands, Commerce, and Appropriations Committees. His voting record was balanced and moderate by standards of his time. He favored tariff reductions, effective regulation of business, a graduated income tax, an expansion of the money supply, the building of the Panama Canal, and direct election of U.S. senators. He opposed giving women the vote, extending the civil service, restricting adulteration of food, and annexing Hawaii. He opposed U.S. territorial expansion and imperialism, especially in the Philippines. In a speech before the U.S. Senate on June 3, 1902, he called the Philippine action “an unjust and unholy war,” brought about by greedy U.S. citizens “actuated by wild dreams of commercial prosperity and expansion” and contrary to our republican tradition.

In 1900, Berry faced Arkansas governor Daniel Webster Jones and retained his Senate seat. A young firebrand, Jeff Davis, lent his support to Berry during that campaign largely because he disagreed with Jones over several issues. Jones wanted to build a new state capitol, and he opposed rigorous application of the Rector Anti-Trust Law. Davis’s support for Berry would last just one senate term.

One of the measures Berry supported, direct election of senators, played a role in his defeat during the 1906 senatorial election. His opponent was Jeff Davis, now governor of Arkansas. Berry had never campaigned statewide for office. At age sixty-five, he was slowing down. During this, his first direct election, he was ill-prepared. Berry remarked, in a June 1905 letter to Judge Allen Hughes of Jonesboro (Craighead County), “I do not think it probable that Davis and I will meet in a joint debate…. I do not think we will ever be able to agree on any kind of terms.” Berry lost the election and retired to his home in Bentonville.

Berry remained active in the Arkansas chapter of the United Confederate Veterans and served for a short time as a member of the Arkansas History Commission (now called the Arkansas State Archives). In 1910, President Taft asked Berry to serve as commissioner in charge of marking the graves of Confederate soldiers who died in Union prisons. Pleased and honored to take on this last official public service and efficient as usual, he completed the task ahead of schedule and under budget.

In the political spectrum between redeemer and reformer, Berry is positioned somewhere in the middle—perhaps as a conservative reformer. He saw the benefit of change, but he wanted it to be gradual and respectful of tradition. Berry’s last speech as governor, in 1885, summarizes his career and his outlook: “Others have served the state better, but no one can be bound to her by stronger ties or more earnestly desire the happiness of the people.” He died of heart failure on January 30, 1913, and is buried in City Cemetery (Knights of Pythias) in Bentonville.

For additional information:

Berry, James H. “An Autobiography of James H. Berry, Soldier, Jurist, Governor, U.S. Senator.” Arkansas Gazette. February 9, 1913, p. 5.

Berry, Dickinson, Peel Family Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

James Henderson Berry Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Mulhollan, Paige E. “The Issues of the Davis-Berry Senatorial Campaign in 1906.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Summer 1961): 118–125.

———. “The Public Career of James H. Berry.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1962.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

George W. Balogh

Conway, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.