calsfoundation@cals.org

Howard County Race Riot of 1883

aka: Hempstead County Race Riot of 1883

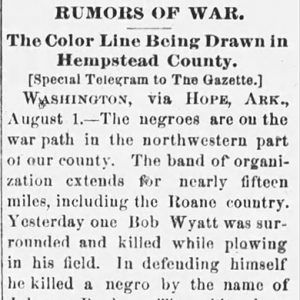

The Howard County Race Riot occurred along the Howard and Hempstead county line in late July and early August 1883. Two events spurred the outbreak of violence. First, a disagreement over the surveying of a property line led to the beating of Prince Marshall and his brother James Marshall, both African-American farmers, by Thomas Wyatt, a white sharecropper living on land owned by Joseph Reed, a white farmer. Second, a few days later, Wyatt is alleged to have approached a young black woman, a member of Prince and James Marshall’s family, as she was plowing alone in a field and “solicited” her. When she began to cry out, he hit her over the head with a fence rail. The latter event spurred the black men in the community to take action.

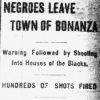

Members of the black community had approached a local justice of the peace in Mine Creek Township in Hempstead County and an attorney in Washington (Hempstead County), seeking advice and help. Dissatisfied with the assistance received, they met in a local black church in late July and determined to organize a group of men to make a citizen’s arrest of Thomas Wyatt. The next day, they gathered to march to Wyatt’s home to apprehend him. In the ensuing altercation, Joe Booker, the group’s alleged leader, was shot to death. Wyatt was also killed; his body was found in a cotton field just over the line in Howard County. White posses quickly formed and sought Wyatt’s killers. Telegrams from Washington alerted the Arkansas Gazette, which first reported on the event on August 2, 1883.

Posses ranged through the countryside looking for Wyatt’s killers. One went north to the home of Joe Booker. This posse, led by John Bell, killed Eli Gamble, a neighbor and carpenter building Booker’s coffin; his helper and relative, a young farmer named Alonzo Flowers; and a teenage boy named Abraham Booker, a bystander. The second posse went south toward Columbus (Hempstead County) to the home of Sam Johnson, a prosperous black farmer. Johnson had already gone to Washington to seek help. The posse surrounded his home. Shooting ensued, followed by a standoff. James F. Smith, a well-to-do and influential merchant from Mineral Springs (Howard County), managed to defuse the situation though he was himself wounded.

With the countryside in an uproar, rumors abounded. Some whites felt that a full-blown insurrection was afoot, while some African Americans feared a brutal attempt to seize black property. Governor James H. Berry sent General Robert C. Newton of the state militia to bring order. Armed posses held prisoners at Mineral Springs before they were transferred to jails in Center Point (Howard County) and Washington. Eventually, forty-three African-American men held at Center Point were charged with murder. Another group of African- American men held at Washington was charged with rioting and released pending trial.

On November 12, 1883, the trials began for the African-American men at Center Point. After difficulties in jury selection, Charles Wright, who had pleaded not guilty, was tried first, found guilty, and quickly sentenced to death. On November 21, Henry Carr and Elijah Thompson were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced with Wright to hanging. Julius Y. Johnson was sentenced to eighteen years for second-degree murder. Frightened, the other men changed their not-guilty pleas, resulting in ten men being sentenced to fifteen years, nine men to ten years, and ten men to five years. Ten men were released without charges.

Wright was hanged at Center Point on April 25, 1884. Carr and Thompson received a new trial in Clark County. The men evaded execution by pleading guilty to second-degree murder and were sentenced to eighteen years.

In October 1884, the men charged with rioting came before the Washington court. Four men, including Sam Johnson and Prince Marshall, had their charges dismissed when they proved they were not present at the site of the riot. The jury acquitted three other men. Eight other men were found guilty of rioting and fined ten dollars each. When the men protested the size of the fine, Judge George Smoote reduced it to one dollar per man.

Even with the death penalty off the table, the men convicted in Howard County had to endure harsh circumstances in the Arkansas state prison in Little Rock (Pulaski County). In September 1884, however, Governor Berry pardoned the surviving men given five-year sentences at Center Point. In January 1886, Governor Simon P. Hughes pardoned all but three of the men convicted in Howard County who were still incarcerated. By that time, one man had escaped, and six men had already died in prison. In September 1890, Governor James P. Eagle pardoned Henry Carr. Presumably, Thompson and James Marshall Sr. were also pardoned about this time.

For additional information:

Lloyd, Peggy S. “The Howard County Race Riot of 1883.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Winter 2000): 353–387.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Peggy S. Lloyd

Washington, Arkansas

I am a descendent of Thomas Wyatt. This story was told to me by my great-grandfather, Walter Wyatt, son of W. J. Wyatt.