calsfoundation@cals.org

Italians

Few people associate Arkansas with Italian immigration to America, assuming immigrants settled only in the urban Northeast. Yet many communities throughout the United States have a significant proportion of Italian Americans. Lured by work and regional ties, immigrants gravitated to places they could find work, whether in garment factories, coal mines, farms, fisheries, the canning industry, or lumber mills. Italians have also played a major role in the state’s winemaking heritage. Immigrants sought out established settlements of their village compatriots, or paesani. Certainly in the peak immigration years (1880–1910), the American South—including Arkansas—attracted its share of Italian immigrants. According to the National Italian American Foundation, the 2000 Census reported that just 1.3 percent (36,674 people) of the state’s population was of Italian-American descent; while the Arkansas numbers are not large, Italian Americans have maintained a presence since the nineteenth century. Though an ethnic minority in Arkansas, Italian Americans have had a consistent and significant impact on the economic and cultural development of the state.

The first Italians to visit Arkansas were the early explorers. The most noteworthy was Henri de Tonti (1649?–1704), often referred to as the “Father of Arkansas.” A soldier, explorer, and fur trader, de Tonti sailed under the French flag, accompanying René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle on his explorations of the Mississippi River in the 1680s. In 1686, de Tonti established a trading post that became Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), the state’s first permanent Euro-American settlement.

More than 200 years later, a major episode in the history of Italian-American immigration to Arkansas occurred—the settlement of Sunnyside Plantation in Chicot County. While Italians had worked on the levees of the Mississippi River Delta in the early 1800s, about 1,000 people came from Italy to this area in southeastern Arkansas in the late nineteenth century. A group of ninety-eight families came to farm the cotton plantation at Sunnyside in 1895. The recruitment of these laborers was the brainchild of New York financier Austin Corbin, president of the Sunnyside Company. He turned to Italy as a source of inexpensive labor, and the immigrants came mainly from central and northern Italy. They were to be obligated to the company for twenty-two years before owning the land they worked. What they failed to realize was the company controlled the gin, the packing house, the railroad through the plantation, and the area’s only store. A second group arrived in January 1897, but the settlement was unsuccessful for several reasons: Corbin, who had spearheaded the project, died in 1896. His heirs lacked both the interest and the managerial skills necessary to make the project a success. Moreover, the immigrants found the adjustment to Arkansas’s climate especially difficult; the farmers did not have experience with the cotton and sugarcane crops; the price of cotton had dropped; and, most significantly, many immigrants died as a result of a malaria epidemic because a drainage project had never been completed.

While some of the settlers remained in the Arkansas Delta, acquired their own land, and became cotton farmers, others moved to an Italian community in St. Genevieve, Missouri, or to Alabama. Some Sunnyside settlers left with Father Pietro Bandini in 1898. Seeking a healthier climate, thirty-five families settled in Washington County, naming their community Tontitown in honor of the Italian explorer. Bandini believed the Ozarks more closely resembled the region in Italy from which these immigrants originated. The men worked various jobs, including in coalmines in Oklahoma, to make payments on their land. They first tried to grow apples, but disease killed that crop. They ultimately chose grapes, having vines shipped from Italy. This proved successful, and by 1921, Welch’s Grape Juice Company opened a plant in nearby Springdale (Washington and Benton counties).

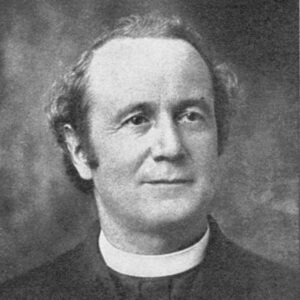

Bandini (1852–1917) is a major figure in the history of Italian-American immigration to Arkansas. A Jesuit priest, he did missionary work among Native Americans in Montana. Eventually he became affiliated with the St. Raphael Society, an order founded by Bishop Giovanni Baptista Scalabrini to work with Italian immigrants in the United States. He did social work with immigrants in New York. In 1897, he was assigned to Sunnyside and provided aid and leadership to the immigrants. Instrumental in establishing Tontitown, he made the initial down payment on the land from his own funds, built St. Joseph’s church and parochial school there, organized the Tontitown Band, and was elected Tontitown’s first mayor. Even while supervising the new community at Tontitown, Bandini did not forget his fellow Italians at Sunnyside. He arranged for Father F. J. Galloni to come from Italy to minister to those still at the plantation. Galloni later moved to Lake Village (Chicot County) and supervised the construction of its church and parochial school.

In spite of Sunnyside’s lack of success, immigrants lured by false promises continued to go there until World War I. By 1910, new management altered the agreement that had bound previous tenants. They were now to pay rent, and the landlord would receive twenty-five percent of their crop. This was even less satisfactory for the immigrants. Moreover, the U.S. Justice Department had begun investigating the Sunnyside system in 1907. Special Agent Mary Grace Quackenbos’s report brought to light the harsh treatment of the 160 families and their unhealthy living conditions, and implicated the company in violation of federal alien contract labor laws and federal peonage laws. While her efforts were thwarted in the United States, the Italian government curtailed immigration to Sunnyside. By the 1920s, no Italians were left at Sunnyside, though many remained in the Lake Village area.

Although unsuccessful, other plantation owners used Sunnyside’s model and recruited Italians to work the land. South of Sunnyside, across Lake Chicot, Italian immigrants worked the Red Leaf plantation until a flood in 1912 forced their evacuation. In 1905, John M. Gracie brought northern Italians to work on his plantation New Gascony (Jefferson County). In 1911, twenty-nine Italian families worked for him. Most remained on the plantation until 1921 when Gracie lost his land. Some of the original family names can still be found in Arkansas today: the Fratesis, Turchis, Massanellis, Pallazzis, Mancinis, and Palacinis. With better living and working conditions than Sunnyside, the Dockery plantation near Marion (Crittenden County) also drew a significant number of Italian immigrants. Many were employed by Will Dockery, while others worked on farms in the vicinity of Marion. Some of these families eventually started grocery and dry goods stores, restaurants, shoe shops, and other businesses in the area.

Agriculture was not the only draw for Italians. Like many other ethnic groups, some went to Bauxite (Saline County) to mine and process the bauxite used in making aluminum. In the early 1900s, sections of town reflected immigrants’ origins; one was known as “Italy.” The Premier Cotton Mill in Barton (Phillips County) recruited Italian immigrants as well. The mill, which produced yarn, primarily employed women and children. Working under brutal conditions, young boys received twenty-five cents and girls fourteen cents for their dawn-to-dusk workday. Immigrants also settled in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and other places. Cigainero Hill in Texarkana (Miller County) was established in the 1800s when Giovanni Battista Cigainero settled there with his wife and family. In 1915, a group of Italian immigrants who wanted to escape the urban problems of Chicago, Illinois, established Little Italy in Perry County and Pulaski County. And while most Italians arrived in Arkansas looking for work and a better life, some came to the United States as prisoners of war. St. Charles (Arkansas County) and Monticello (Drew County) were sites of camps for Italian prisoners during World War II.

One Italian-American immigrant contributed extensively to the cultural life of Arkansas and became the state’s second poet laureate. Born in Bologna, Italy, in 1888, Rosa Zagnoni Marinoni came to the United States as a child. Her family settled in New York, where her father was a journalist. She married Antonio Marinoni, who became the first head of the Romance Languages Department at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). She began writing poetry after an automobile wreck. She also wrote fiction, including children’s stories. She was poet laureate from 1953 until her death in 1970.

The long presence of Italian Americans in Arkansas is evident in a variety of ways. Place names, such as Tontitown, reflect the state’s ethnic heritage. Annual events also mark an Italian-American identity. The Grape Festival held every August in Tontitown has its origin in a dinner that Father Bandini organized in 1898 as a way for the settlers to celebrate and offer thanksgiving for their new home. Social organizations such as the Circolo Italiano in Little Rock and the bocce courts throughout the state highlight an Italian-American presence. Many Arkansas businesses are of Italian-American origin. Little Rock has been the home of Jacuzzi Brothers, and North Little Rock (Pulaski County) became home to Jason International, Inc., founded by its president, Remo Jacuzzi; Pasquale’s Tamales in Helena-West Helena (Phillips County) was started by Sicilian immigrant Pasquale St. Columbia, a peddler in the Delta who learned to make tamales from Mexican-American workers and whose descendants now run a thriving business. Piero’s Bistro in Jonesboro (Craighead County), owned and operated by Florence-born Piero Trimarchi, featured fusion cuisine. The recipes and stories handed down from generation to generation are continuing reminders of the immigrant ancestors who left their native Italy for Arkansas.

For additional information:

Bailey, Susan L. “Poets Laureate of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Spring 1990): 51–56.

Borgognoni, Elizabeth “Libby” Olivi. Italians of Sunnyside: The History—from 1895. 2nd ed. Lake Village, AR: Italians of Sunnyside Foundation, 2024.

Braun, Lauren Hillary. “Italians, the Labor Problem, and the Project of Agricultural Colonization in the New South, 1884–1934.” PhD diss., University of Illinois at Chicago, 2010.

Braun-Strumfels, Lauren. Partners in Gatekeeping: How Italy Shaped U.S. Immigration Policy over Ten Pivotal Years, 1891–1901. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2023.

Canonici, Paul V. The Delta Italians: Their Pursuit of “The Better Life” and Their Struggle against Mosquitoes, Floods, and Prejudice. N.p.: 2003.

Dorer, Christopher A. Boy the Stories I Could Tell: A Narrative History of the Italians of Little Italy, Arkansas. Winfield, KS: Central Plains Book Manufacturing Co., 2002.

———. “Little Italy: A Historical and Sociological Survey.” Pulaski County Historical Review 51 (Summer 2003): 43–54.

“Growing up Italian: A History of the Lovoi/Caldarera Family in Fort Smith, Arkansas.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 18 (April 1994): 2–13.

Keltner, Robert W. “Tar Paper Shacks in Arcadia: Housing for Ethnic Minority Groups in the Company Town of Bauxite, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Winter 2001): 341–359.

Lewellen, Jeffrey. “‘Sheep amidst the Wolves’: Father Bandini and the Colony at Tontitown, 1898–1917.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45 (Spring 1986): 19–40.

Milani, Ernesto. “Marchigiani and Veneti on Sunny Side Plantation.” In Italian Immigrants in Rural and Small Town America. Edited by Rudolph J. Becoli. Staten Island, NY: American Italian Historical Association, 1987.

“Moses in the Ozarks: The Parable of Italians in the South.” The Economist, May 25, 2017. Online at http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21722683-migration-race-charismatic-priest-and-lots-cannelloni-parable-italians (accessed August 2, 2023).

Mullins, Camille Elise. “Italians in the Delta: The Evolution of an Unusual Immigration.” Honors thesis, University of Mississippi, 2015. Online at https://thesis.honors.olemiss.edu/307/1/CAMILLE%20ABSOLUTE%20FINALDep.pdf (accessed August 2, 2023).

Smith, Sibyl. “Notes on the Italian Settlers of Pulaski County.” Pulaski County Historical Review 38 (Fall 1990): 51–57.

Tebbetts, Diane Ott. “Transmission of Folklife Patterns in Two Rural Arkansas Ethnic Groups: The Germans and Italians in Perry County.” PhD diss., Indiana University, 1987.

Whayne, Jeannie M., ed. Shadows over Sunnyside: An Arkansas Plantation in Transition. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Frances M. Malpezzi

Arkansas State University

My daddy’s mother and uncles’ last name was Caplena in Brinkley and Cotton Plant 1920s.

My grandmother told me that she was taken to Perry County by her father, Pietr Bracci or Brachi, around the turn of the century. They were working in the wine industry and he was a supervisor. They left because of malaria. They came from Corinaldo, Italy, near Ancona on the Adriatic, went to Sao Paulo, Brazil, then to New Orleans and up the Mississippi. My grandmothers sister Augusto was born there in Perry County. They were already in Brooklyn and then Massachusetts by 1910, so they predated the group that you cite in your entry on Little Italy.

My great-grandparents’ names were listed as some of the Italians who moved to Sunnyside Plantation, from northern Italy. Antonio Tisato and his wife Risa (Cicchelero) Tisato were their names. Im trying to figure out what exact part of Italy they were from.