calsfoundation@cals.org

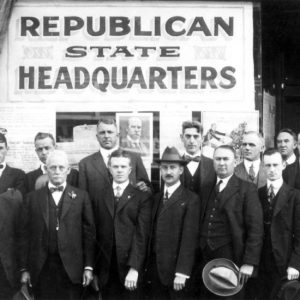

Harmon Liveright Remmel (1852–1927)

Harmon Liveright Remmel succeeded Powell Clayton as leader of Arkansas’s Republican Party in 1913. His tenure was plagued by an ongoing dispute between Lily White and African-American Republicans. His role in the movement remains a topic of debate among historians.

Harmon Remmel was born on January 15, 1852, in Stratford, New York, to German immigrants Gottlieb Remmel and Henrietta Bever. Gottlieb Remmel was a tanner and a staunch Republican. Harmon Remmel, who had four brothers and two sisters, attended Fairfield Seminary in Fairfield, New York. He taught school for a year, and in 1871, he and his brother Augustus Caleb (A. C.) Remmel entered the lumber business in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In 1874, he returned to New York, and in 1876, he and his brother moved to Newport (Jackson County), forming the Remmel Brothers Lumber Company.

On March 13, 1878, Remmel married Laura Lee Stafford of Virginia. She died in October 1913, and in 1915, he married Elizabeth I. Cameron of New York. He adopted her daughter, Elizabeth. They had one son, Harmon L. Remmel Jr.

In 1886, he received an appointment as a lieutenant colonel in the state militia, afterward being known as “the Colonel.” That same year, he left the lumber business and moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County), becoming the Arkansas general manager of the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York, a position he held until 1922. In 1902, he organized the Mercantile Trust Company, serving as its president until 1912. From 1910 to 1912, he was president of the Little Rock Board of Trade. He helped organize the Bankers’ Trust Company in Little Rock, serving as president from 1914 to 1923. He was president of the Arkansas Banker’s Association in 1921.

Remmel used his business expertise for the state. In 1909, he was appointed to the commission overseeing the building of a new state capitol building. In 1910, he became chairman of the Arkansas Good Roads and Drainage Association. With the nation’s entry into World War I, he became a member of the Arkansas State Council of Defense. An advocate of the light and power industry, he arranged for an interview between Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L) founder Harvey Couch and Secretary of War John Weeks, resulting in a license for Arkansas’s first hydroelectric dam to be built on the Ouachita River at Jones Mill (Hot Spring County) near Hot Springs (Garland County). Completed in 1924, it was named Remmel Dam in his honor.

Remmel became a powerful figure in the state Republican Party. He was elected to Newport’s town council in 1876, serving two terms. In 1886, he was elected to the state House of Representatives, representing Jackson County. He lost races for governor and U.S. representative and senator. In 1884, he obtained what became a lifelong appointment to the Republican state central committee. He was a delegate to each Republican National Convention from 1892 to 1924. In 1895, he was elected president of the Arkansas League of Republican Clubs. In 1897, he succeeded Clayton as Arkansas’s representative in the Republican National League, and in 1900, he became chairman of the state Republican central committee. In 1916, he resigned as chairman of the party; his nephew, Augustus Caleb (A. C.) Remmel Jr., succeeded him. After his nephew died, he resumed chairmanship of the party in 1921.

Remmel benefited from Republican administrations, receiving federal patronage appointments, including postmaster of Newport in 1877 and secretary of the state Bureau of Immigration in 1888. In 1897, he was appointed state collector of internal revenue. But, learning that a rival, Henry M. Cooper, marshal for the Eastern District of Arkansas, received a higher salary, Remmel expressed disgruntlement. Clayton arranged that the difference of the two salaries would be split between Remmel and Cooper, and that held until 1902, when President Theodore Roosevelt learned of the deal and chose not to reappoint the two. In 1903, Remmel was appointed marshal for the Eastern District of Arkansas and resigned as chairman of the Republican central committee, but he resumed that role in 1910. He was appointed state collector of internal revenue again in 1921, a position he held until his death.

Despite moving to Pulaski County, Remmel retained his Jackson County Republican affiliation. When Clayton retired in 1913, Remmel succeeded him as Arkansas’s member of the Republican National Committee and thus became leader of the state party. But a dispute between white and black Republicans erupted again in 1914. The Lily White Republicans—young white Republicans led by his nephew, A. C. Remmel Jr.—sought to expel black Republicans from leadership positions in the party in hopes of making the party more appealing to racist whites, who traditionally voted for Democrats. Remmel’s role in the dispute remains unclear. He chastised the Lily Whites in 1914. In 1916, he voted to seat a Lily White delegation from Pulaski County to the state convention but also seconded the nomination of Elias Camp Morris, a black leader from Helena (Phillips County), as a national convention delegate. In 1920, he remained within the Lily White–controlled state convention after a walkout by black delegates that he viewed as an empty and divisive gesture. In 1924, Remmel opposed further efforts to exclude African Americans as delegates. Nevertheless, the position of African Americans in the state Republican Party had been permanently weakened. Reflecting the weakened position was the fact that, prior to 1916, the state convention had always reserved one of the “Big Four” national convention at-large delegate positions for an African American. This was often complemented by additional delegates from the state’s congressional districts. However, in 1928, only a single African American, Little Rock (Pulaski County) attorney Scipio Jones, was appointed as a delegate to the national convention, and this was as a representative of the Fifth Congressional District.

Also in 1924, Remmel was approached by members of the state Ku Klux Klan, who offered Klan support for Republican candidates in the coming election. Unlike the Klan of Reconstruction, which had been primarily concerned with white supremacy and restoring political power to whites who had been disfranchised for their support of the Confederacy, the Klan of the 1920s added anti-Catholicism, nativism, and fundamentalist Protestantism to racism as pillars of its ideology. A meeting was arranged to take place in Chicago, Illinois, between Remmel and James A. Comer of Little Rock, former head of the state Bull Moose Republicans and then-leader of the state Klan. However, whether the meeting took place is unknown, and, if so, any deal made had little impact on the 1924 state election contests, which Democrats won overwhelmingly.

In May 1927, Remmel suffered a stroke. While recovering at Ozark Sanitarium in Hot Springs, he contracted pneumonia, dying on October 14, 1927. He is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Besom, Bob. “Little Rock Businessmen Invest in Coal: Harmon L. Remmel and the Arkansas Anthracite Coal Company, 1905–1923.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Autumn 1988): 273–287.

Harmon Liveright Remmel Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Lewis, Todd E. “‘Caesars Are Too Many’: Harmon Liveright Remmel and the Republican Party of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Spring 1997): 1–25.

Russell, Marvin F. “The Rise of a Republican Leader: Harmon L. Remmel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 36 (Autumn 1977): 234–257.

Todd E. Lewis

University of Arkansas Libraries

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.