calsfoundation@cals.org

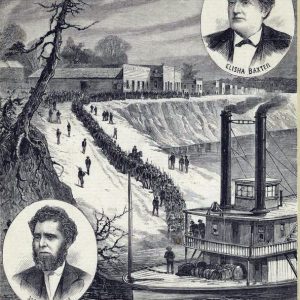

Elisha Baxter (1827–1899)

Tenth Governor (1873–1874)

Elisha Baxter, a Unionist leader during the Civil War and a jurist, is best remembered as Arkansas’s last Republican governor during Reconstruction. The attempt to overthrow him became known as the Brooks-Baxter War. Baxter’s victory resulted in the end of Reconstruction and the adoption of the Constitution of 1874.

Elisha Baxter was born on September 1, 1827, in Rutherford County, North Carolina, to William Baxter and his second wife, Catherine Lee. She was the mother to five sons and three daughters out of William Baxter’s twenty children. His father had emigrated from Ireland in 1789 and prospered in Rutherford County in western North Carolina, acquiring land and slaves. Baxter received a limited education and sought to better himself by obtaining an appointment to the military academy at West Point. However, his father, who was nearly ninety years old, forced him to decline the appointment because he wanted this son to stay at home.

In 1847, he entered into a successful general mercantile business with a brother-in-law, Spencer Eaves. Baxter married Harriet Patton of Rutherford County, North Carolina, on August 16, 1849. They had six children. His youngest brother, Taylor A. Baxter, married her sister, Charity. After the death of his father at ninety-three and the settlement of his estate, Elisha and Taylor moved to Batesville (Independence County) in 1852, where the Baxters went into the mercantile trade. He was elected Batesville’s mayor in 1853 and, in the same year, became one of Independence County’s three members of the Arkansas House of Representatives in the Tenth General Assembly (1854–1855).

In 1855, the Baxters’ firm failed. Baxter then became a typesetter for the Independent Balance newspaper while studying law under Hulbert F. Fairchild, who served on the Arkansas Supreme Court from 1860 to 1864. Admitted to the bar in 1856, he paid off all his debts and returned to politics, being elected to the Twelfth General Assembly in 1858. He was narrowly defeated in a bid to become the prosecuting attorney for the Seventh Judicial Circuit in December 1861.

A Whig at the time of his arrival in Arkansas and in the first stages of his political career, Baxter was forced to find a new political home after the demise of the Whigs. During the late 1850s, he supported the extremist states’ rights Democrat Thomas Carmichael Hindman, probably because Hindman was attempting to overthrow the entrenched “Family” machine that had long ruled the state. He and his brother, both jointly and separately, owned slaves, having apparently received some from his father’s estate.

Baxter claimed in his autobiography that he believed secession was “unjust to the Federal Government,” and early historian John Hallum reported that Baxter favored compensating owners for the emancipation of their slaves. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Baxter adhered to the idea of neutrality, a notion popular in the border states in 1861, holding that Arkansas should not participate on either side in the war. However, his name appears as quartermaster of the First Arkansas Regiment, a thirty-day unit (part of the Arkansas State Troops) organized by Confederate Colonel Solon Borland on November 22, 1861, in Randolph County. By contrast, an older brother, John Baxter, took a leading role in opposing secession in Tennessee. In May 1862, Baxter welcomed Union General Samuel Curtis, whose forces had occupied Batesville. After the Union army left the area, the returning Confederates planned retribution, causing local Unionists to flee. Furthermore, Baxter was expelled from the Methodist Church without a hearing.

Once safe within Union lines at Jacksonport, Baxter was offered the command of the First Arkansas Infantry (US). He declined Curtis’s offer, explaining years later, “whilst I believed the rebellion was wrong I did not feel that it was my duty to make War upon the people of the South.” He was teaching school at Patterson, Missouri, on April 19–20 when Colonel Robert C. Newton captured him and carried him back to Little Rock (Pulaski County), where he was indicted for treason and jailed with Enoch H. Vance. He and Vance escaped when, in late August, Vance’s wife smuggled in the key. Baxter survived for about two weeks on green corn and berries. Little Rock was falling to Major General Frederick Steele’s Union army, but Baxter’s suffering was prolonged because he was unable to distinguish friend from foe.

After Little Rock fell on September 10, Baxter was rescued. First, he sued personally the members of the grand jury that had indicted him; second, he accepted Steele’s commission to raise a Union regiment in the Batesville area. Baxter began recruiting the Fourth Arkansas Mounted Infantry but afterwards resigned his commission in order to assume a position on the newly constituted state Supreme Court organized under the Constitution of 1864. His command was never officially recognized by the federal government. Taylor A. Baxter followed his brother into the Union army but subsequently moved to Kansas.

Governor Isaac Murphy’s newly organized Union government hoped to gain recognition from Congress as well as from President Abraham Lincoln by filling the two United States Senate vacancies. Baxter was the first chosen, with little opposition. However, a firestorm of opposition arose in Little Rock to the second nominee, William H. Fishback, who had voted for secession at the state convention in May 1861. When Baxter and Fishback attempted to claim their seats in Washington, Radical Republicans turned both away after having made a shambles of Fishback’s claims to loyalty. Nothing ever was said about Baxter’s reported thirty-day participation on the Confederate side. This event seriously compromised President Abraham Lincoln’s plan for restoring states to the Union. Congress thereafter refused to seat representatives and senators from southern states, although it considered Lincoln’s Reconstructed states competent to ratify the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

The newly organized Republican Party gained control of Arkansas after the adoption of the Constitution of 1868. Governor Powell Clayton appointed Baxter judge of the Third Judicial Circuit in 1868, an office he held until 1873. In 1868, Baxter became the registrar in bankruptcy for the First Congressional District, an office he held simultaneously with his judicial office.

By 1872, the Republican Party was badly split. The dominant faction was the Clayton-led Minstrels faction, composed heavily of new immigrants (then known as “carpetbaggers”). Their opponents, the Brindletails, so called because of the bellowing voice of their leader, Joseph Brooks, made the strongest appeal to ex-Confederates by promising to re-enfranchise them. The third element of the party, the newly enfranchised African Americans, could be found in both camps. At the time, it was considered a masterpiece of political acumen when the Clayton-led faction chose to nominate Elisha Baxter for governor: a native Unionist (or “scalawag,” as such people were called), to oppose the “Brindletail” faction’s candidate, “carpetbagger” Joseph Brooks, whose policies of amnesty for ex-Confederates and economic retrenchment had great popularity among white voters.

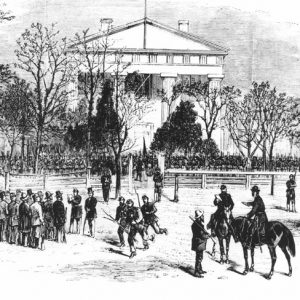

The close and hotly contested race was decided by the legislature in Baxter’s favor due to Clayton’s Minstrels faction having control of that body. Brooks appealed to the courts, but his suit went nowhere until Governor Baxter began openly courting Democrats by supporting restoring voting rights to former Confederates; then on March 16, 1874, he also questioned the legality of the state’s multi-million-dollar railroad aid program. Clayton, by now a United States senator, concluded that Baxter could not be trusted. Returning from Washington, he reached an agreement to support Joseph Brooks, who at least was sound on the bond issue. Brooks’s long dormant case was called up, and without Baxter’s lawyer even being present, Brooks was declared judicially to be Arkansas’s governor. Brooks and his armed force physically ousted Baxter from the State House on April 15, 1874, thus beginning the Brooks-Baxter War. Immediately, the state divided into armed and often violent camps.

During the war, Baxter’s name figured in a battle song sung to the tune of “Good-Bye, My Lover”:

Do you see that boat come round the bend?

She’s loaded down with Baxter men—

Good-bye, lover, good-bye.

The war claimed at least 200 casualties before President Ulysses S. Grant reluctantly acted to restore Baxter to power. Baxter seems to have stayed in his hotel room and was at times heavily medicated. Both governors appealed to the president, but Brooks rejected referring the disputed election to the state legislature. Grant had a much bigger crisis underway in Louisiana, and dubious of the methods that had brought about Brooks’s elevation, he sided with Baxter. On May 13, the legislature set an election on June 30 regarding the adoption of a new constitution. By a vote of 80,250 to 8,607, voters called into session a new constitutional convention that, by restoring ex-Confederates’ right to vote, guaranteed the return of the Democrats to power. Baxter became the hero of the day for sacrificing two years off his term, and Brooks was placated by the job of Little Rock postmaster.

Meanwhile, a congressional committee headed by Luke P. Poland of Vermont held hearings on the legality of Baxter’s restoration. The committee’s majority report supported Baxter, but President Grant now embraced the minority report. The newly assembled convention meanwhile drafted a new constitution for Arkansas, which the voters adopted on October 13, 1874. The Democrats offered Baxter—who had thus lost two years off his original term when the new constitution vacated all offices—the gubernatorial nomination that fall, but he twice rejected it on the grounds that he did not want to appear to profit from his abandonment of the Republican Party. In the first election held along with the ratification of the Constitution of 1874, Augustus H. Garland became governor in Baxter’s place. In 1878, Baxter sought a seat in the United States Senate, but the Democratic Party rejected him. He then retired from politics.

Baxter returned to Batesville and practiced law. Baxter County, created on March 24, 1873, was named in his honor. In 1888, he erected a substantial two-story house. He remained active in Methodism, having helped organize a Northern Methodist church in Batesville in 1866. In 1881, he led his small white Methodist congregation into joining the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The Northern Methodists’ former building, Lafferty Methodist Episcopal Church, became the property of the town’s black Methodists. He also served as a delegate to the Cape May Methodist conference that began the process of reunifying America’s Methodists. He died on May 31, 1899, after a month’s illness, and is buried in Batesville’s Oaklawn Cemetery. The Arkansas Gazette, in a lengthy obituary, praised Baxter for returning the state to the Democrats and suggested Democrats should honor him by building a large monument over his grave. However, no such monument was ever built. One of his surviving children was the well-known north Arkansas physician Dr. Edward A Baxter, who explained that his father “always tried to avoid trouble.”

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard Gatewood, Jr., and Jeanne Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

“Gov. Baxter Dead.” Arkansas Gazette, June 2, 1899, p. 3.

Hallum, John. Biographical and Pictorial History of Arkansas. Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1887.

Harrell, John M. The Brooks and Baxter War: A History of the Reconstruction Period in Arkansas. St. Louis: Slawson Printing Co., 1893. 1893. Online at https://archive.org/details/brooksbaxterwarh00harr/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed March 6, 2024).

Ross, Margaret. “Governor Elisha Baxter Was a Unionist—And He Suffered for It in Civil War.” Chronicles of Arkansas. Arkansas Gazette. December 4, 1966, p. 6E.

Worley, Ted R., ed. “Elisha Baxter’s Autobiography.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 14 (Summer 1955): 172–175.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

I have a copy of William Baxter’s will, six typed pages long. He left to his son, Elisha Baxter: his Negro boy, Dick; his tract of land purchased from Johnston; two 50-acre tracts he purchased from William Webb; 100 acres and also the 50 yards along the north side of the Fling Tract as excepted in the bequest of his daughter Sara Suttle; and $50 to purchase a horse. He was to pay William’s son, Taylor, $250 when he reached the age of 21. To his daughter, Esther McDowell Durham, he left $1,600 and the price of the five Negroes left in trust for her benefit. For another daughter, he left her property for her brother to manage because her husband was given to strong drink and not trustworthy. There is another story about William (second generation). He and his twelve-year-old son and his thirteen-year-old niece were slain on the night of September 30,1838, by a slave who, along with several other slaves, had been sold in Georgia by William Baxter. The new owner of the slaves persuaded the slave to follow William and rob him of the money he had been paid. The slave waited until they had retired for the night in their covered wagon. He took the axe left beside their camp fire and killed William, his son James, and his niece Caroline. My great-grandmother, Catherine Mahala Suttle Harrill, had a lock of Caroline’s hair among her keepsakes. Her house was destroyed by fire in 1897 and it was lost. They are buried in the Baxter Family cemetery about four miles from where I live in Forest City, NC.