calsfoundation@cals.org

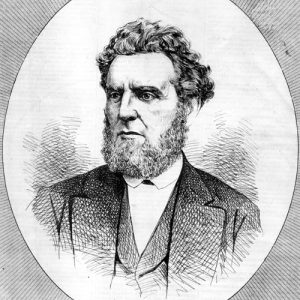

Joseph Brooks (1821–1877)

Joseph Brooks was a Methodist minister who came to Arkansas during the Civil War. He played a prominent role in postwar Republican politics. He ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1872 and was one of the participants in the subsequent Brooks-Baxter War.

Joseph Brooks was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on November 1, 1821. Nothing is known of his parents or his early family life. He attended Indiana Asbury University in Greencastle, Indiana, now DePauw University, and after graduation entered the ministry of the Methodist Episcopal Church. He was ordained in 1840 at the age of eighteen. His first assignment was as a circuit rider, traveling across an assigned territory to preach. He later rode circuit in Iowa, then moved to Illinois, where he served as the financial agent of the Methodist Northwestern University in Evanston. In 1856, he settled in St. Louis and became editor of the Central Christian Advocate, a Methodist anti-slavery paper, which gave him a forum for his own strong abolitionist sentiments. Prior to the move to St. Louis, Brooks married Eliza Goodenough. The couple had six children, including Ida Brooks, later a prominent advocate of women’s suffrage in Arkansas and one of the state’s first female doctors. In addition to his newspaper activities at St. Louis, according to his daughter Ida, Brooks amassed a fortune dealing in cotton, only to lose it in New Orleans in the early years of the Civil War.

Brooks was appointed chaplain of the First Missouri Artillery at the outbreak of the Civil War and then moved to the Eleventh Missouri Infantry. In the summer of 1862, he became chaplain of the Thirty-third Missouri Infantry, stationed at Helena (Phillips County). In Helena, Brooks became involved in organizing African American units and, in the fall of 1863, became chaplain of the Third Arkansas Infantry (African Descent), later renamed the Fifty-sixth United States Colored Infantry, which was commanded by his brother, William. Brooks remained associated with the regiment until he resigned from the army in February 1865.

Brooks was interested in the freedmen, and after his resignation from the army, like many other Union officers he secured a government lease to operate an abandoned cotton plantation near Helena. Brooks recouped some of his fortune in his wartime farming efforts. After the war, he invested in a Phillips County plantation, which he operated profitably. In 1867, Brooks became active in the organization of black citizens into the Republican Party in Phillips County. He achieved the reputation of a radical due to the speeches that he gave across the countryside, advocating the seizure of the lands of those who had supported the Confederacy and their division among the freedmen. He also became one of the few white advocates for granting of full civil rights to black citizens. His efforts secured him a place in the Arkansas Constitutional Convention of 1868, where he continued to advocate full equality before the law in the constitution, as well as the right to vote, for African Americans. Able to attract black supporters because of his political stand, Brooks emerged as one of the principal early leaders of the state Republican Party, along with Benjamin F. Rice, a retired officer from the Third Minnesota who later became one of the state’s United States senators, and James L. Hodges, another so-called carpetbagger who was named postmaster of Little Rock (Pulaski County) and worked as a contractor on the state’s railroads.

Brooks remained in Little Rock after the convention and received a patronage appointment as Assessor of Internal Revenue for the Treasury Department’s Second District of Arkansas. The job allowed him to carry on his efforts as a Republican organizer across his district. Military officials named him one of the commissioners to supervise the 1868 election on the ratification of the proposed constitution. Brooks was active in Ulysses S. Grant’s presidential campaign in the autumn of 1868, traveling across the state to organize black voters and give support to his candidate. That October, while campaigning in Monroe County, a man later identified as George A. Clark ambushed Brooks and Congressman James M. Hinds. Brooks survived, but Hinds died from wounds received in the attack. Brooks also became a member of the state House of Representatives, replacing J. N. Tobias of Helena, who died in 1868. He initially was a strong supporter of Governor Powell Clayton, especially the governor’s efforts at crushing the Ku Klux Klan by imposing martial law in certain parts of the state. At the same time, Brooks’s support of the franchise of the Cairo and Fulton Railroad raised charges, never substantiated, that he had taken bribes to push a bill favorable to that franchise through the legislature—charges which tarnished his reputation.

Brooks early proved to be much more radical than his party’s leaders. In 1868, he broke with Clayton to form what became known as the “Brindletail” faction of the Republican Party. The faction was named for Brooks, who was said to have a voice like a brindletail bull. Brooks expressed concern with Clayton’s moderate programs and urged more far-reaching economic and social programs to assist black and lower-class white citizens, groups that he considered to be the core of the party’s strength. In 1870, he helped arrange an anti-Clayton slate in the legislative and congressional elections. He ran for the state Senate from Pulaski County in an election that saw widespread fraud. Brooks charged that Democrats had stolen the election, and the Senate initially seated him. He held the position for only a short time and was removed when the Senate reversed itself and seated his Democratic opponent, Wilshire Riley.

In 1872, the Brindletail Republicans held a state convention and nominated Brooks as their candidate for governor. He organized the Reform Republican Party, endorsing, with his supporters, the national Liberal Republican Party and its presidential candidate, Horace Greeley. Locally, Brooks appealed to voters concerned with the direction of the government under Clayton by promising to cut government expenditures, reduce taxes, limit the appointive powers of the governor, and end corruption. Brooks also promised to end the disenfranchisement of former Confederates, which had been incorporated into the 1868 state constitution. These promises to end disenfranchisement secured the support of some of the state’s Democratic leaders, who endorsed his platform despite expressing concern about his radical positions on race issues in the past; others backed Elisha Baxter. His new position marked a major reversal in the politics he had earlier advocated.

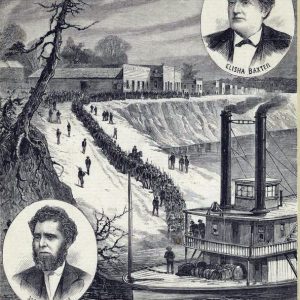

The subsequent election set up a period of political unrest that lasted for the next two years. Brooks lost the election to Elisha Baxter, the candidate of the regular Republican faction, commonly called the “Minstrels” because one of its leading members had allegedly been a member of a minstrel troupe. Baxter’s victory depended on a decision by state election officials to throw out the votes of four counties for alleged irregularities, and had these votes been counted, Brooks would have been elected. Brooks proceeded with a challenge to the election and gathered evidence of fraud, even after his opponent was inaugurated on January 6, 1873. Governor Baxter began to make overtures to former Confederate leaders (including the naming of a prominent ex-Confederate officer as head of the state militia), pushed forward an end to disenfranchisement of former Confederates from serving in the legislature, and then broke with party leaders over railroad legislation. John McClure—chief justice of the state Supreme Court, editor of the Daily Republican, and a prominent Minstrel—shifted his support from Baxter and encouraged Brooks in his efforts in challenging the election.

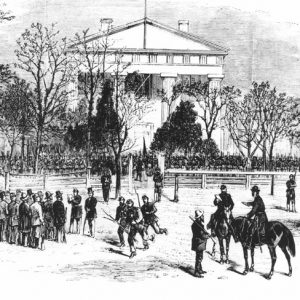

In April 1874, the Pulaski County Circuit Court decided in favor of Brooks’s claims to the governorship in a case filed by Brooks two years earlier. When Baxter refused to concede the election to Brooks, Brooks’s supporters removed Baxter from the governor’s office by force. Others quickly armed and gathered to Baxter’s support. From April 15 to May 15, several armed engagements between the two forces occurred, turning the election contest into what became known as the Brooks-Baxter War. Brooks even considered creating a rival state government in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Ultimately, both sides appealed for recognition from the national government, forcing Congress to establish a committee to investigate Arkansas affairs. Initially, President Ulysses S. Grant supported Brooks, whom he considered a real Republican, but many in the North had become increasingly disillusioned with intervention in Southern affairs, and congressional Republicans did not want to become involved in the Arkansas situation. Grant gave in to the new circumstances and, acting upon the legal opinion of Attorney General George H. Williams, acknowledged Baxter as the rightful governor. With no help from either Congress or the president, Brooks ceased his contest of the election. The congressional committee ultimately concluded that Baxter’s claim was, indeed, stronger than Brooks’s.

Still recognized as a loyal Republican, Brooks received the appointment of postmaster of Little Rock from President Grant the same month he ceased the election contest. Brooks made peace with his political opponents in his own party and participated in the Republican Party’s state convention in 1876. Rumors suggested he might be the party’s nominee for governor that year, but he did not secure that honor. Reports indicated that he had begun to suffer from the illness from which he ultimately died.

Brooks died in Little Rock on April 30, 1877, and he is buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

For additional information:

Atkinson, James. H. “The Arkansas Campaign and Election of 1872.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 1 (December 1942): 307–321.

De Black, Tom. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Harrell, John M. The Brooks and Baxter War: A History of the Reconstruction Period in Arkansas. St. Louis: Slawson Printing, 1893. 1893. Online at https://archive.org/details/brooksbaxterwarh00harr/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed March 6, 2024).

Williams, Nancy, ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Woodward, Earl F. “The Brooks-Baxter War in Arkansas, 1872–1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Winter 1971): 315–36.

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.