calsfoundation@cals.org

Des Arc (Prairie County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º58’37″N 091º29’42″W |

| Elevation: | 205 feet |

| Area: | 2.10 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 1,905 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | December 28, 1854 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

548 |

546 |

640 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,061 |

1,307 |

1,348 |

1,410 |

1,612 |

1,482 |

1,714 |

2,001 |

2,001 |

1,933 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,717 |

1,905 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

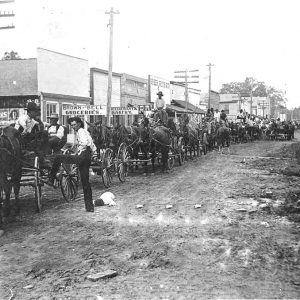

Des Arc is one of two county seats serving Prairie County. It was one of the earliest settlements in eastern Arkansas as well as an important shipping point for lumber and agricultural goods.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Des Arc was the earliest settlement in Prairie County, taking its name from the Bayou des Arc two miles north of city; the bayou’s name is derived from a French term meaning “bow” or “curve.” Francis Francure, a Frenchman, was reportedly one of the first settlers in the area, testifying, upon receipt of a Spanish land grant, that he had lived on the land since 1789. Goodspeed’s history of the area credits as the first residents two Creoles named Watts and East, who arrived around 1810. Later pioneer families included the Runkles, Coburns, Goforths, and McAnultys. Various early documents spell the name of the city as Des Ark, des Arques, Desarc, Desare, Des Arcs Bluff, and Dezark Bluff, or refer to the city as Francisville or McNulty’s Bluff. Early settlers cut hay, raised stock, and grew corn, wheat, rye, and cotton.

In the late 1840s, two landowners laid out their respective landholdings into town lots, and the city of Des Arc grew from that point. One of these landowners, James Erwin, soon opened the first store, a combination cotton and grist mill, and a sawmill. The city’s placement along the White River proved especially profitable in the early years, and Des Arc was a point at which local timber was shipped downstream to other markets; trees common in the area included walnut, hickory, ash, and other hardwoods. In the 1850s, the Butterfield Overland Mail Company ran through Des Arc, thus making it an important stop for mail and travelers between Memphis, Tennessee, and points west. The city’s first newspaper was the Des Arc Citizen, established in September 1854 by John C. Morrill. The Des Arc Constitutional Union was founded in 1860 to combat the secessionist editorial stance of the Citizen. In December 1859, the city formed a vigilance committee to prevent disturbances and local slave rebellions; there were 552 slaves in White River Township, of which Des Arc was a part, in 1860.

In the late 1850s, Des Arc engaged in a heated rivalry with Little Rock (Pulaski County) over the course of a railroad stretching from Memphis, Tennessee, to Fort Smith (Sebastian County), though Little Rock won. On November 29, 1858, the aldermen of the city passed a resolution to move the state capital from Little Rock to Des Arc, though nothing ever resulted from this. In 1860, the state legislature incorporated the Des Arc and Fort Smith Railroad, though it was never built due to the Civil War.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

A Confederate company was organized in Des Arc in the spring of 1861. In January 1863, Major General Samuel Curtis, who had captured Helena (Phillips County) in 1862, led an expedition up the White River after deciding that it would be too costly to traverse the Grand Prairie to Little Rock, the prairie at the time having been covered in snow that was then melting, turning it into “one vast sheet of water.” After taking DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), he proceeded to Des Arc. He described his capture of Des Arc as a “handsome success,” taking 100 prisoners, ammunition, and corn, along with destroying a telegraph and all the ferries across the river at the city.

Various military actions continued to occur in the area, such as the July 14, 1864, Action at Des Arc Bayou, which occurred north of the city. Confederate guerrilla Howell A. “Doc” Rayburn operated in the vicinity of Des Arc from 1863 until the end of the war. Des Arc was partially destroyed during the war, and some of the city’s buildings were disassembled and transported south to DeValls Bluff for use by the Union army. However, the townspeople were able to rebuild, and, in 1875, Des Arc became the seat of Prairie County, taking that honor away from DeValls Bluff, which had been designated the county seat in 1868. Ten years later, a second judicial district was created in DeValls Bluff because of regular flooding along the White River, which runs through the county. In 1869, an African American man named Jeff Johnson was lynched near Des Arc.

Des Arc had no public school until 1872. In April 1877, approximately 125 local residents who had joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints left Des Arc to venture to Utah. On July 10, 1881, a Black man named Henry Smith was lynched in Des Arc. The Agricultural Wheel, a state farmers’ union, was founded eight miles southwest of Des Arc on February 15, 1882. It eventually expanded into ten other states and became a major source of populist and third-party activism across the state and nation. In 1883, a two-story brick courthouse building was erected in Des Arc. In 1892, a new school building was constructed to handle an increasing student body.

Early Twentieth Century

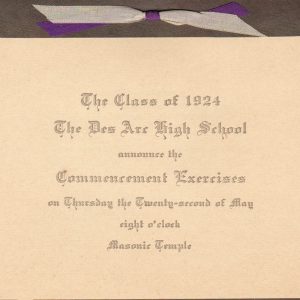

In 1900, the Des Arc and Northern Railroad was built, running from Des Arc to St. Louis, Missouri, for the purpose of transporting lumber. Under a merger, it became the Searcy and Des Arc Railroad. Des Arc’s importance grew even further as rice began to be planted on the Grand Prairie in the early years of the twentieth century. By 1906, more than 4,000 acres of prairie were under rice cultivation, and the lucrative nature of the crop resulted in the city’s population more than doubling between 1900 and 1920. The school building expanded in 1910; the twelfth grade was added to the curriculum in 1920. In 1930, the Des Arc School District consolidated with ten neighboring rural school districts and built a two-story brick schoolhouse to accommodate the new students.

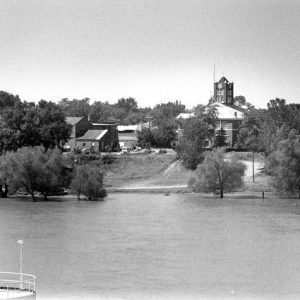

During the Great Depression, New Deal agencies did provide some relief to the people of Des Arc. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) aided in the construction of an American Legion hut in 1934; this building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The school district had to get federal aid in 1934 in order to remain in operation. The Flood of 1927 and the Flood of 1937 hit Des Arc hard, and local rescue operations had to be carried out.

A privately owned toll bridge over the White River at Des Arc became one of the centerpieces of Governor Carl Bailey’s efforts against bridge companies in the state. After a spate of lawsuits, the state was able to acquire the bridge for $50,000 in 1939 and convert it to public use.

World War II through the Modern Era

In 1945, the White River broke through a levee constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, flooding Des Arc once more. However, another flood four years later proved even worse, with the White River cresting at 37.35 feet.

After the School Reorganization Act of 1948, the Des Arc School District subsumed even more rural school districts. In response, a new high school building was constructed in 1951. The school district finally desegregated during the 1966–1967 school year under the leadership of Superintendent James Ford. In 1970, prominent local citizen John Bethell founded the Des Arc Archeological Center Bethell Pioneer Museum, incorporating much of his private collection into the museum. It is now the Lower White River Museum State Park.

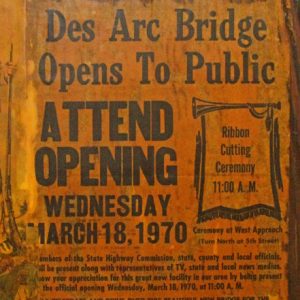

A new bridge over the White River at Des Arc opened on March 18, 1970. In 1973, another flood hit the city, though it was not as bad as previous floods. From the 1970s onward, the school district experienced a steady decline in students, even though Des Arc’s population was at its highest point yet in 1980 and 1990 (the 2000 and 2010 censuses showed declining population, however). A new high school complex opened in 1984, and, the following year, the district joined the Wilbur D. Mills Education Service Cooperative. State budget cuts in 1986–87 created numerous problems for the local school district, threatening its closure, at least temporarily. However, fundraisers, combined with a student trip to Little Rock to lobby for a refund of state monies, saved the school.

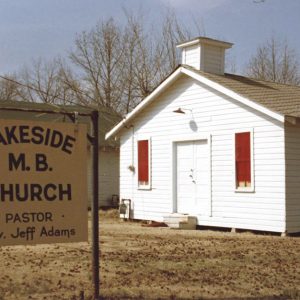

In 1992, Acco-Babcock, an automotive parts factory and the largest employer, closed up shop. A tornado struck Des Arc on December 18, 2002, damaging homes and destroying the school district’s bus shop. Des Arc remains a local center of agricultural production. Riceland Foods maintains a grain dryer in the city, and numerous fish hatcheries are located in the area.

Attractions

Among the many properties in Des Arc listed on the National Register of Historic Places are Oak Grove Cemetery, a public cemetery dating back to 1851; the 1858 Frith-Plunkett House; the 1918 Bethel House, designed by noted architect Charles Thompson; and the 1913 Prairie County Courthouse. Boating, hunting, and fishing opportunities are available at the nearby Bayou des Arc Wildlife Management Area, the Wattensaw Wildlife Management Area, or the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge.

Notable Residents

Lurlyne Greer Rogers, who was hailed as one of the best women’s basketball players of the late 1940s and early 1950s, was born in Des Arc and graduated valedictorian from the local high school.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Garth, H. K. A History of Des Arc High School, 1870–2004. Des Arc, AR: 2005.

Worley, Ted R. Early History of Des Arc and Its People. Des Arc, AR: White River Journal, 1957.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.