calsfoundation@cals.org

Clarendon (Monroe County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º41’43″N 091º18’22″W |

| Elevation: | 174 feet |

| Area: | 1.83 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 1,526 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | February 8, 1859; August 11, 1898 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

400 |

1,060 |

1,840 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

2,037 |

2,638 |

2,149 |

2,551 |

2,547 |

2,293 |

2,563 |

2,361 |

2,072 |

1,960 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,664 |

1,526 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

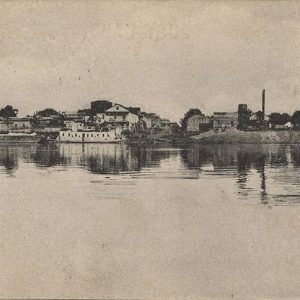

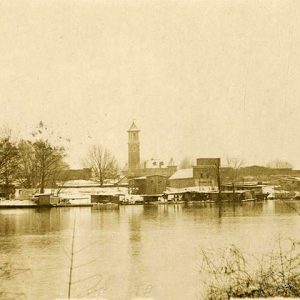

Clarendon is located on the White River near the mouth of the Cache River. It became an early settlement as a river town for transportation purposes, although frequent flooding plagued the community.

European Exploration and Settlement through Early Statehood

The area was settled around 1799 by French hunters and trappers who had established cabins at the mouth of Cache River before the Louisiana Purchase.

Various accounts, without explanation, have stated that the town is named for the Earl of Clarendon of England.

Constructed in the mid- to late 1820s, the Military Road from Memphis, Tennessee, crossed the White River at Clarendon to its destination in Little Rock (Pulaski County), increasing Clarendon’s importance as a river port. By 1828, a ferry crossing and post office were established, likely attracting more settlers.

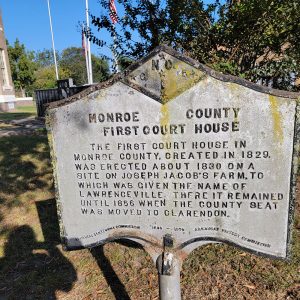

Monroe County was created on November 2, 1829, by the territorial legislature from portions of Arkansas and Phillips counties, with Clarendon becoming its county seat; it remains so to this day. The town was not formally incorporated until February 8, 1859, with William H. Thweat commissioned as the first mayor on May 12, 1859.

By the last half of the 1850s, Monroe County, along with the rest of the Arkansas Delta region, experienced unparalleled economic growth with slave-based, plantation-style farming, and cotton was the focus of the transformation of subsistence farming to large-scale operations.

Civil War and Reconstruction

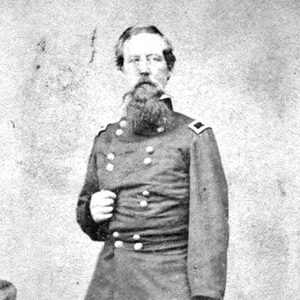

The White River served as an important byway for the Union forces during the Civil War and was heavy with gunboat traffic, with Clarendon serving as a skirmish point. Supplies for Major General Frederick Steele’s Federal army were brought to DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), north of Clarendon, by way of the White River and were shipped from there to Little Rock by railcar. Various skirmishes and battles took place in and around Clarendon, and Confederate forces were decisively defeated in July 1862 by Union forces under General Samuel Curtis, whose march on Clarendon culminated in Federal control of the general area. Union forces returned to Clarendon the following month under Brigadier General Alvin P. Hovey but remained less than a week. The Clarendon Expedition of August 4–17, 1862 resulted in the Union’s capture of Clarendon.

On June 19, 1864, Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby of the Confederacy led his force on a march through the Cache River overflow bottoms to within two miles of Clarendon, where they camped awaiting an attack on Federal gunboat No. 26, the USS Queen City, then moored at Clarendon. On the night of June 23, Shelby’s forces entered the town, taking positions overlooking the river. By 4:00 the following morning, the Confederates opened fire on the boat with artillery and small arms fire. Upon the surrender of the crew, they sacked the boat and sank it near the current railroad bridge located there. Under heavy artillery fire from other gunboats, Shelby’s forces were driven from the town on June 25 and were pursued for about thirty miles by Union forces, who were unsuccessful in capturing them. Union forces then promptly burned a large part of the town of Clarendon in retaliation. In October of that year, another expedition resulted in Union forces gathering military intelligence and limiting guerrilla retaliation on nearby Union ships.

After the war, the town resumed its role as an important industrial port for cotton and other commodities. The Moore-Jacobs House, constructed around 1870, was home to author Margaret Moore Jacobs and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Monroe County Sun, the town’s current newspaper, was established in 1877.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

A railway bridge was constructed in 1883 by the St. Louis Southwestern Railway (Cotton Belt), though the ferry continued to operate until 1931, when it was replaced with the current highway bridge system. The rail line—which was commonly known as the Cotton Belt—was originally incorporated in 1879 as the Texas and St. Louis Railway, providing service between Clarendon, Jonesboro (Craighead County), and Texarkana (Miller County).

In 1876, a white man named only Johnson in newspaper reports was lynched in town for having allegedly murdered two people. In 1887, an African American man named Leach Magee was also lynched for allegedly assaulting a woman who was the relative of the local sheriff. The town’s original charter was dissolved in 1884, though Clarendon was reincorporated in 1898. This same year a group of five African Americans were lynched for their involvement in the murder of a prosperous white man. The Merchants and Planters Bank was established in 1890; the original building still stands as of 2010 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Industries and cultural development began with a stave and barrel factory in 1889, an oar factory in 1892, and an opera house constructed in 1893.

Early Twentieth Century

Clarendon continued to develop new industries after the turn of the century, including lumber mills and a button factory producing buttons made from mussel shells found in the river. Freshwater pearls were sold at the Clarendon Pearl Market. The Moss Brothers Bat Company, which produced baseball bats, was also established.

On June 25, 1903, an African American man named Jack Harris was lynched in Clarendon for allegedly attacking his employer, planter John A. Coburn.

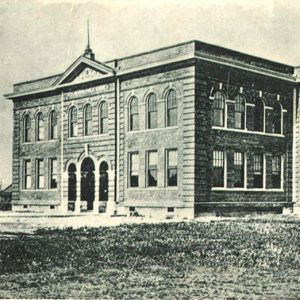

The Monroe County Courthouse was designed by noted Arkansas architect Charles L. Thompson and constructed in 1911. It remains the town’s most significant landmark.

Clarendon was devastated by the Flood of 1927. The main levee held until the White River reached a level of 38.5 feet—8.5 feet above flood stage. The town was inundated with water, causing massive damage to buildings. Floods continued to plague the area, though the 1927 flood was the most devastating. A new levee was constructed in 1937, lessening the impact of high water on the White River.

In 1927, the Arkansas legislature passed a bill appropriating $52 million to develop the state highway system, which included the construction of the Clarendon bridge, completed in 1931.

The Flood of 1927 occurred on the eve of the Great Depression in 1929, which was followed by the Drought of 1930–1931—the worst drought in Monroe County’s history. These natural disasters had profoundly harmed Clarendon and the surrounding agricultural area.

World War II through the Modern Era

Clarendon’s citizens, as did the rest of the country, made their contribution to the cause during World War II; forty-seven soldiers from Monroe County died during the war.

During the mid-1950s, the town had a box factory and a thriving fish market, along with a bustling downtown with shops including apparel and dry goods stores and a movie theater. In addition, the town had a thriving public school system. However, along with much of the Arkansas Delta, the town has experienced an economic downturn from that heyday. As of 2010, with the exception of the local public library, a bank, and two law offices, the remainder of the old downtown shop buildings are shuttered and closed, including the movie theater, and the town is without an industry presence.

The local economy does receive some contribution from tourism related to hunting and fishing in the area and its close proximity to the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge.

Notable residents

Donald Gene Dyer, a basketball coach with 601 collegiate victories to his name, grew up in Clarendon.

For additional information:

Biographies and Historical Memoirs of Western Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Clarendon. http://www.arkansas.com/places-to-go/cities-and-towns/city-detail.aspx?city=clarendon (accessed April 19, 2022).

English, Jo Claire. Pages from the Past Revisited: Historical Notes on Clarendon, Monroe County and Arkansas. Clarendon, AR: J. C. English, 1991.

Roberts, Jeannie. “Struggling Delta Town Sees Possibilities.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 21, 2018, pp. 1A, 6A–7A.

W. R. Mayo

Delta House Publishing Company/Indian Bay Press

Alvin P. Hovey

Alvin P. Hovey  Bank of Clarendon

Bank of Clarendon  Entering Clarendon

Entering Clarendon  Clarendon Bridge

Clarendon Bridge  Clarendon Access

Clarendon Access  Clarendon Bridge

Clarendon Bridge  Clarendon Button Factory

Clarendon Button Factory  Clarendon City Hall

Clarendon City Hall  Clarendon Civil War Marker

Clarendon Civil War Marker  Clarendon Fire Department

Clarendon Fire Department  Clarendon Flood

Clarendon Flood  Clarendon Flood

Clarendon Flood  Clarendon High School

Clarendon High School  Clarendon High School

Clarendon High School  Clarendon Hotel

Clarendon Hotel  Clarendon Methodist Church

Clarendon Methodist Church  Clarendon Post Office

Clarendon Post Office  Clarendon Refugees

Clarendon Refugees  Clarendon Riverfront

Clarendon Riverfront  Clarendon Riverfront

Clarendon Riverfront  Clarendon Street Scene

Clarendon Street Scene  Clarendon Water Tower

Clarendon Water Tower  Clarendon Welcome Center

Clarendon Welcome Center  Courthouse Historical Sign

Courthouse Historical Sign  Cumberland Presbyterian Church

Cumberland Presbyterian Church  Cumberland Presbyterian Church

Cumberland Presbyterian Church  Fishing Pond

Fishing Pond  Monroe County Courthouse

Monroe County Courthouse  Monroe County Courthouse

Monroe County Courthouse  Monroe County Map

Monroe County Map  Monroe County War Memorial

Monroe County War Memorial

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.