calsfoundation@cals.org

Buffalo National River

aka: Buffalo River

The Buffalo National River, which runs through Newton, Searcy, Marion, and Baxter counties, became the first national river in the United States on March 1, 1972. It is one of the few remaining free-flowing rivers in the lower forty-eight states. The Buffalo National River, administered by the National Park Service, encompasses 135 miles of the 150-mile long river.

President Richard M. Nixon signed Public Law 92-237 to put the river under the protection of the National Park Service 100 years after the establishment of Yellowstone National Park, the first national park. The law begins, “That for the purposes of conserving and interpreting an area containing unique scenic and scientific features, and preserving as a free-flowing stream an important segment of the Buffalo River in Arkansas for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations, the Secretary of the Interior… may establish and administer the Buffalo National River.” Behind that sentence, which set the mission for the park, were decades of debate and discussion regarding the use, ownership and management of the Buffalo River.

The Buffalo River originates in the Boston Mountains of the Ozark Plateau. Flowing generally from west to east, the river traverses Newton, Searcy, and Marion counties before flowing into the White River just inside the border of Baxter County. Although termed a national river, the park includes lands (such as private lands under easement) surrounding the river, as well as the river itself, for a total acreage of 94,293.

The river was an attraction for the area’s inhabitants from prehistoric times to the first European and American settlements of the late 1820s, and many of their cultural sites are located in the park. These sites range from terrace village sites, to bluff shelters once occupied by Archaic Period Indians, to cabins built by early settlers.

It provided flood plain terraces for agricultural fields, transportation for such local industry as timbering or mining, food, and recreation. Although somewhat isolated by the terrain, the area’s population fluctuated with the economy and outside influences, such as war, but at no time could the area be considered prosperous. Nevertheless, the residents who remained after World War II felt a strong bond to the land and what had been a way of life for 150 years.

The Buffalo River and its surrounding Ozarks scenery were long admired for their beauty and potential for development. Two state parks were created along the river: Buffalo River State Park in 1938, constructed as a project of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) under the direction of the National Park Service, and Lost Valley State Park in 1966. The river’s hydroelectric potential was also appreciated. With the passage of the Flood Control Act of 1938, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers included the Buffalo River in its planning for a system of dams on the White River. Two potential dam sites eventually were selected on the Buffalo, one on the lower portion of the river near its mouth and one at its middle just upstream from the town of Gilbert (Searcy County).

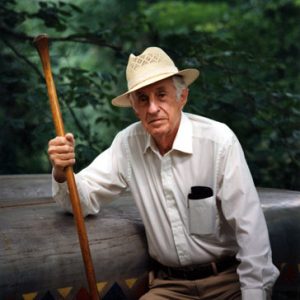

The continual threat of a dam on the Buffalo caught the attention of Arkansas conservation groups and those who had begun using the river for recreation or simply appreciated the free-flowing river as a spectacular natural resource for the state. In the early 1960s, advocates for the dams and advocates for a free-flowing stream formed opposing organizations. The pro-dam Buffalo River Improvement Association, established by James Tudor of Marshall (Searcy County), and the anti-dam Ozark Society, which included environmentalist Neil Compton, emerged as the leading players in the drama.

The dam proponents worked with the Corps of Engineers and Third District Congressman James Trimble. The free-flowing stream advocates made overtures to the Department of the Interior. In 1961, a National Park Service planning team undertook a site survey of the Buffalo River area. The team was favorably impressed and recommended the establishment of a park on the Buffalo River to be called a “national river.”

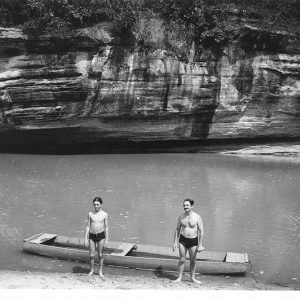

A decade of political maneuverings, speeches, and media attention—including a canoe trip on the Buffalo by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas—came to a head in December 1965, when Governor Orval Faubus wrote the Corps of Engineers that he could not support the idea of a dam on the Buffalo River. The Corps withdrew its proposal for a dam. In 1966, John Paul Hammerschmidt defeated Trimble for the Third Congressional District seat and indicated that he would support the concept of creating a park along the river. Congressman Hammerschmidt and Senators J. William Fulbright and John L. McClellan introduced the first Buffalo National River park legislation in 1967. The final park legislation was introduced in 1971, and hearings were held in late 1971. In February 1972, Congress voted to establish the nation’s first “national river.”

Park acreage, boundaries, and special considerations were written into the legislation. Total acreage could not exceed 95,730 acres. (As of the most recent land purchase in 2022, the park as 94,293 acres.) Hunting and fishing were allowed as a traditional use. Many permanent residents had an option of use and occupancy up to twenty-five years. Landowners in the three private use zones of Boxley Valley, Richland Valley, and the Boy Scout camp at Camp Orr could choose to sell easements to the government instead of selling the land outright.

The first park management staff—the park superintendent, a chief ranger, and a secretary—arrived in 1972 and took up temporary office quarters in Harrison (Boone County). Eventually, the park was divided into three management districts with staff in each district. Besides setting up park facilities and developing programs, the staff also had to face the emotional turmoil in the community regarding the disruption of life for the Buffalo River residents, whether they were willing or unwilling sellers.

Following the establishment of a C&H/Cargill hog farm in 2013 near Mount Judea (Newton County) in the Buffalo River valley, some—including the Buffalo River Watershed Alliance—expressed concerns that the waste runoff from the operation threatened to pollute the river. In April 2017, the American National Rivers (AMR) preservation advocacy group ranked the Buffalo as one of America’s ten most endangered rivers due to the threat from hog farm pollution. AMR called on Governor Asa Hutchinson and the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) to deny C&H’s permit to operate its farm. Since the installation of the hog farm, the Buffalo River experienced several algal blooms; significant algae growth in the summer of 2018 included toxic blue-green algae. In July 2018, a 14.3-mile segment of the river and Big Creek, a tributary, was listed as impaired, meaning that the level of pathogens exceeded state water quality standards. In 2018, ADEQ denied C&H its permit to operate. In 2019, the Buffalo was listed on America’s Most Endangered Rivers. Later that year, C&H took a $6.2 million buyout from the state, with the land being given to the state as a conservation easement in order to protect the river. On October 25, 2024, the Arkansas Division of Environmental Quality‘s Pollution and Ecology Commission voted to update state environmental regulations to include a ban on concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in the watershed of the Buffalo River; the proposed rule required approval by the Arkansas Legislative Council but encountered stiff opposition from the Arkansas Farm Bureau and the Arkansas Cattlemen’s Association. During the 2025 legislative session, Senator Blake Johnson of Corning (Clay County) sponsored SB 290, a bill that would limit the ability of state agencies to place a moratorium on industrial farming operations in Arkansas’s watersheds, including the Buffalo River. However, at the urging of Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the bill was amended to preserve the two existing moratoria covering the Buffalo River and the Lake Maumelle watersheds.

The Buffalo National River is one of the leading tourist destinations in Arkansas. Park headquarters are located in Harrison. Park visitation has averaged more than 800,000 visitors a year. Visitors can access the 135 miles of river within the park at launch points all along the river, but the U.S. Forest Service protects the river’s headwaters. Along with water activities, the park offers more than 100 miles of hiking trails as well as designated trails for horseback riding. The park also includes three congressionally designated wilderness areas. As predicted in the early planning studies, the park’s overall array of resources is its greatest significance. In June 2019, the Buffalo National River was designated the first International Dark Sky Park in the state of Arkansas.

The park has four historic districts on the National Register (including the Big Buffalo Valley Historic District and the Parker-Hickman Farm Historic District), as well as individual sites depicting the cultural history of the river’s peoples. The park’s karst topography includes Fitton Cave, the longest known cave in Arkansas. Other caves in the area are home to endangered bat populations. Mammals range from familiar river animals, such as the beaver and raccoon, to land species, such as deer, elk and black bear. Smallmouth bass and catfish tempt the fisherman, but more than fifty fish other species have been recorded in the river. Bird and plant populations are varied and extensive and represent a healthy ecological system. At the center flows the undammed, free-flowing Buffalo River, fed by tributaries and springs and dramatic “pour-offs” down the limestone bluffs—truly, in the words of native son songwriter Jimmy Driftwood, “Arkansas’s gift to the nation, America’s gift to the world.”

In July 2022, staff of the Runway Group, a privately held company founded by Steuart and Tom Walton, grandsons of Walmart founder Sam Walton, met with U.S. Representative Bruce Westerman to promote the idea of designating the national river the Buffalo National Park Preserve, but no bill has yet been filed in the U.S. Congress. In late 2023, the Madison County Record broke the news about the proposed redesignation and the purchase of large tracts of area land by the Walton family, sparking tremendous local concern about the future of the Buffalo and its environs. On October 26, 2023, at the cafeteria of the local school in Jasper (Newton County), an overflow crowd of 1,135, more than twice the population of the town, met to air concerns. Proponents of the redesignation tout the likelihood of an increase visitation and federal infrastructure funding, while opponents worry about additional restrictions on land use and possible overcrowding. In the face of local opposition, the Runway Group announced that it was backing off plans to promote the redesignation, and on December 1, 2023, the Arkansas Farm Bureau officially adopted a policy opposing any potential redesignation.

In February 2025, the Buffalo Point Visitor Contact Station was closed “until further notice” as the result of a wave of firings across all branches of the federal government that was initiated by President Donald Trump and billionaire Elon Musk. Fired employees returned to work in late March after two federal judges handed down orders requiring that the Trump administration rehire probationary employees removed during these mass firings.

For additional information:

Bowden, Bill. “Buffalo River Proposal Stirs Foes.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 27, 2023, pp. 1A, 5A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/oct/26/more-than-1100-people-attend-meeting-on-re-designating-buffalo-national-river/ (accessed October 27, 2023).

———. “Buffalo River Visitor Center to Stay Closed.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 27, 2025, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2025/feb/26/one-of-two-visitor-centers-closed-at-buffalo/ (accessed February 27, 2025).

———. “National Park Designation for Buffalo River Considered.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 7, 2023, pp. 1A, 4A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/oct/07/national-park-status-considered-for-buffalo/ (accessed October 10, 2023).

———. “Park Delights in Starry, Starry Nights.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 16, 2019, pp. 1B, 7B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2019/jun/16/park-delights-in-starry-starry-nights-2-1/ (accessed October 10, 2023).

———. “Trail Study Proposed of Buffalo River Area.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 1, 2023, pp. 1A, 4A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/nov/01/state-proposes-buffalo-river-area-trail-study/ (accessed November 1, 2023).

Buffalo National River. http://www.nps.gov/buff (accessed July 6, 2023).

Compton, Neil. The Battle for the Buffalo River. A Twentieth-Century Conservation Crisis in the Ozarks. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Dyer, Patrick M. “Water Quality Contributions of Selected Buffalo River Headwaters in Searcy County, Arkansas, 2019–2023.” MS thesis, Arkansas State University, 2024.

Gallman, Judith M. “An Unspoiled River.” Arkansas Times, March 1992, pp. 46–52.

Kerr, Robert. “Occupied Territory.” Arkansas Times, December 1988, pp. 40–46, 48–50.

Kreth, Ellen. “Buffalo River Land Tangled in Crosscurrents.” Madison County Record, October 25, 2023. https://mcrecordonline.com/stories/buffalo-river-land-tangled-in-crosscurrents,31977? (accessed November 1, 2023).

———. “Locals Fight to Preserve ‘Way of Life’ around Buffalo River.” Madison County Record, November 1, 2023. https://mcrecordonline.com/stories/locals-fight-to-preserve-way-of-life-around-buffalo-river,32810 (accessed November 1, 2023).

Leveritt, Mara. “Riding the Buffalo(s).” Arkansas Times, June 2, 1995, pp. 21–27.

Liles, Jim. Old Folks Talking, Historical Sketches of Boxley Valley. Harrison, AR: Buffalo National River, 1998.

McCoy, Caroline. “Loss at the Buffalo National River: Two Former National Park Service Employees’ Stories.” Oxford American, February 27, 2025. https://oxfordamerican.org/oa-now/loss-at-the-buffalo-national-river (accessed March 11, 2025).

Medford, Thomas Andrew. “A Pastoral River: Reimagining the Narrative of the Buffalo National River.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2025. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/5962/ (accessed December 22, 2025).

Myatt, Kevin. “The Battle for the Buffalo.” Arkansas Times, June 13, 1997, pp. 10–17.

Pierce, Jason. “Creating the Natural State: Outsiders, Insiders, and the Buffalo National River.” Ozark Historical Review 35 (2006): 34–49.

Pitcaithley, Dwight. Let the River Be: A History of the Ozark’s Buffalo River. Santa Fe: Southwest Cultural Resources Center, 1997.

Ramsey, David. “Hog Farm near the Buffalo River Stirs Controversy.” Arkansas Times, August 15, 2013. Online at https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2013/08/15/hog-farm-near-the-buffalo-river-stirs-controversy (accessed July 6, 2023).

Smith, Kenneth L. Buffalo River Handbook. Little Rock: The Ozark Society Foundation, 2004.

Sparks, Caryl L. “Home or National Treasure: The Struggle to Stop National Protection of the Buffalo River.” MA thesis, Arkansas Tech University, 2016.

Taylor, Michael Ray. “Subterranean Blues: A Trip to Forbidden Caverns on the Buffalo National River.” Arkansas Times, February 2025, pp. 36–44. Online at https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2025/02/03/subterranean-blues-a-journey-to-forbidden-caverns-on-the-buffalo-national-river (accessed February 3, 2025).

Thompson, Brian. Save the Buffalo River… Again! A Story about a National River and a Hog Farm. N.p.: Ozark Society, 2022.

Upholt, Boyce. “The Wonderful River of Oz.” The Bitter Southerner, December 5, 2024. https://bittersoutherner.com/feature/2024/the-wonderful-river-of-oz-arkansas-buffalo-river (accessed December 9, 2024).

Walkenhorst, Emily. “14.3-Mile Section of Buffalo River, Big Creek on State’s Impaired List.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 27, 2018, pp. 1A, 5A.

Suzie Rogers

National Park Service

My great-grandfather was James Franklin Dillard. My grandfather was Ira Dillard. Since we are talking about the Buffalo River, I am the last living heir of Ira and Meta Dillard. My grandfather and his brother Pate Dillard were sons of James Franklin Dillard. Those three built the Dillard ferry. My great-grandfather produced the first church in Fayetteville, the first school, and the river project–all while he ran a sawmill and another lumber business. My grandpa Ira and his brother Pate started building cabins. The Dillard family started that river and I was born in Searcy County. I could swim before I could walk. I grew up on the Buffalo River, Big Bluff, or sometimes Big Creek.

(2020) My grandparents and father were raised in Richland Valley in Searcy County. They worked very hard farming . It’s my heritage. I have camped and floated the river before the government took it and made it a national river. I learned to swim at Pruitt. I was water baptized at Tyler Bend. These farmer and ranchers raised and still raise hogs, cattle, and chickens here. It was so wrong for out-of-state people to move here, this bunch of activists trying to protect the river. They are closing down the hog farm, which was these peoples livelihoods and living income. The hogs barely polluted the river. The tourists are the ones who polluted the river. Im very glad the river became a national river in 1972. But to give the Hensons six million dollars to recompense and another two million dollars of taxpayers money to clean it up is beyond me. Now since the virus outbreak, canoe renters are losing money. Tourism is this areas main source of income, so a word for people who move here or retire here: dont get involved with our way of life. Spend your money here, but don’t trouble the landowners/farmers/ranchers. They are the salt of the earth and provide beef, pork, chicken, and timber. Im all for keeping the environment safe and clean, and the river means everything to me. But its our way of life here. People who live in these hills do not know any other way of life, except to farm and raise produce and beef, pork, etc. And they work hard. The river is clean and fine.

My grandfather, Delos Dodd and wife Winnie Dodd, of Marion and Baxter Counties were appointed managers of the Buffalo State/National Park by Gov. Faubus. This was, I believe, during the 1970s during the debate about whether the Buffalo was to become a National River. I think Delos was “let go” in 1970, but I do not know why. Our family was large, my mother being one of 10, and we enjoyed staying at the park (just outside Yellville). We played on the Buffalo and ate at the park cafe, where my grandmother ran the kitchen. Wonderful food. Gov. Faubus would slip away from the capitol and eat and talk with them for a weekend (it was like his Camp David). I know all about the transition of the River–lived through it, fought for it to be a National River. By the way, I am against the pig farm on or near the river!