calsfoundation@cals.org

Booker T. Washington High School (Jonesboro)

Booker T. Washington High School (BTW) in Jonesboro (Craighead County), also known as Jonesboro Industrial High School (IHS), was the first high school for African Americans in northeastern Arkansas. After some setbacks, BTW ultimately became a source of pride in the Black community, with students coming from across the region to attend the school. BTW closed in 1966 when Jonesboro’s public schools were completely desegregated. In the twenty-first century, the E. Boone Watson Community Center and African American Cultural Center stands on the former BTW site.

After a severe snowstorm in December 1917 destroyed the city auditorium in Jonesboro, the Colored School Improvement Association (CSIA) of Jonesboro lobbied the Jonesboro School Board for the bricks from the dilapidated building to construct a new school for Black students. The Jonesboro City Council granted the bricks to the Black community, and the CSIA raised money for the purchase of a site for the future school. The first lot chosen cost $2,600 and was located at the northeastern corner of Hope and Bridge streets. The bricks were moved to the site and hand-cleaned by Black men, women, and children of Jonesboro. However, several attempts to build the high school were halted.

In July 1922, Superintendent J. P. Womack recruited D. W. Hughes of Marianna (Lee County) to serve as principal of the Cherry Street School—a rickety structure built in 1897 at the corner of Cherry and Citizens streets in Jonesboro—which served first through eighth grades. Shortly after his arrival, Hughes began befriending both Black and white residents of Jonesboro to garner support for a new elementary school building and the addition of a high school department. Hughes and a group of Black residents met with Womack and the board of the Jonesboro Special School District several times to stress the importance of a high school education for Black children. They gained approval, and a new location at the corner of Patrick and Logan streets was made available for what became known as Jonesboro Industrial High School.

Hughes designed the new school, a two-story building constructed by Stuck and Associates of Jonesboro using the bricks from the destroyed city auditorium. IHS opened in February 1924 and contained rooms for manual training, home economics, and elementary and high school grades, as well as an auditorium that could be converted into additional classrooms.

During the Great Depression, in early 1933, the state diverted funds away from education, and the Jonesboro School Board voted to privatize the public school. IHS students were required to pay tuition of fifty cents a week for the remainder of the school year; almost half of the students could not meet the tuition, and enrollment dropped to 196 students.

The federal government’s programs to combat the Depression under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal boosted teacher salaries and provided IHS with a new classroom. In 1935, Principal F. C. Turner asked a group of local citizens from the Black community to recommend a name change for the improved school. IHS became Booker T. Washington High School, named after the renowned Black educator and author.

At the end of World War II, veterans returned to BTW and were granted free tuition under the GI Bill. With returning veterans came a football and basketball team, along with an unlikely school mascot—the Eskimoes. The name was chosen after the basketball team endured the freezing cold while traveling to a state tournament in a partially covered truck.

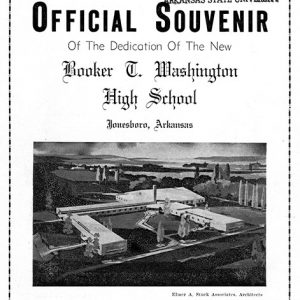

By 1948, the school had become overcrowded and was badly deteriorated. In February 1950, the school board purchased eight acres for a new school site from Clarence Strong, a Black former resident of Jonesboro. The new BTW opened in September 1951 at Houghton Street and Matthews Avenue and was dedicated on September 24, 1951. The board sought national publicity for the event, recruiting Governor Sid McMath to participate in the activities.

To offset the costs of maintaining the building and various components of a high school curriculum, the school board encouraged districts in surrounding communities to send Black students to BTW at their own expense. The board also voted to raise tuition for both Black and white out-of-district high school students—but charged more for Black students. By special arrangement, students from Bay (Craighead County), Lake City (Craighead County), Paragould (Greene County), Biggers (Randolph County), Pocahontas (Randolph County), Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County), Black Rock (Lawrence County), Imboden (Lawrence County), Weiner (Poinsett County), Trumann (Poinsett County), and various unincorporated communities across the Delta and northeastern Arkansas traveled to Jonesboro to attend BTW.

In May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas declared state laws establishing separate public schools for Black and white students to be unconstitutional. The next year, on May 31, 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a second decision requiring schools to integrate with “all deliberate speed.” However, the opening of the new school helped forestall desegregation of public schools in Jonesboro and surrounding areas for over a decade.

In late August 1957, the desegregation crisis at Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County) was beginning to capture national attention. Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) lawyer Wiley Branton, whose suit against the Little Rock School Board led to the desegregation of Central, also challenged the arrangement Jonesboro had with other school districts. He threatened to file suit against the Jonesboro School District and all districts with which it had contracts unless the contracts were canceled and education was provided for Blacks nearer their homes.

During an August 26, 1957, meeting, the Jonesboro Special School District voted to cancel the contracts it had with Paragould, Biggers, Walnut Ridge, and Pocahontas, and to inform all other districts that their contracts would not extend beyond the 1957–58 school year because of over-crowded conditions. Due to “freedom of choice” plans that allowed students to choose between white and Black schools irrespective of their race, BTW recorded an enrollment of fifty-one students in grades one through six on April 11, 1966. The school board thus voted to discontinue use of the BTW building as a school and decided that students would be assigned to the nearest school in which a room was available. The motion passed and resulted in the total desegregation of Jonesboro Public Schools.

The newer BTW building at Houghton and Matthews was used for several different purposes before the building was demolished in 2001. In 1954, the old BTW building at Patrick and Logan streets was torn down, and the Jonesboro School District deeded the property to the City of Jonesboro.

The E. Boone Watson Community Center and African American Cultural Center stands on the BTW site and is dedicated to preserving and remembering Black culture in the town. The center’s collection contains more than fifty exhibits, including photos, newspaper articles, and other pieces of historic memorabilia. BTW alumni have continued to gather from around the country for a reunion in Jonesboro every two years since 1926. Frederick Cornelius Turner Jr., who graduated in 1955, became not only one of the first African American students at what is now Arkansas State University, but also served as the university’s first Black faculty member.

For additional information:

African American Cultural Center Collection. E. Boone Watson Community Center. Jonesboro, Arkansas.

“Board Ends Accepting Negro Pupils from Four Districts.” Jonesboro Evening Sun, August 30, 1957, p. 1.

Education in Craighead County: A Way Out for African Americans. Documentary produced by Robbie L. Lyle and Rights in Education for Students and Parents, 2004.

“NAACP Threat Causes J’Boro School B’rd to Cancel Negro School Contract for This Dist.” Daily Big Picture, September 1, 1957, p. 1.

Smith, Calvin C., and Linda Walls Joshua, eds. Educating the Masses: The Unfolding History of Black School Administrators in Arkansas, 1900–2000. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Amy Ulmer

Arkansas State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.