calsfoundation@cals.org

Agricultural Wheel

The Agricultural Wheel was a state farmers’ union, founded in the Arkansas Delta, which expanded into ten other states, mostly in the South but reaching as far north as Wisconsin. Although the Agricultural Wheel was short-lived as an independent farmers’ union, it influenced the future formation of other such unions in Arkansas and led, in part, to the rise of the Populist movement in the state.

After the Civil War, Arkansas (and Southern) farmers returned to growing primarily cotton, in part because bankers had insisted on farmers raising a cash crop as a condition for providing them with financing. Cotton acreage therefore increased, but prices fell due to overproduction, leading farmers to compensate by planting yet more cotton, which led in turn to even lower prices. As farmers saw their own incomes steadily falling, they realized that those who handled their product—the shippers, warehouses, buyers, and middlemen—were continuing to profit from cotton.

Arkansas farmers also found it difficult to obtain credit: the 1874 state constitution prohibited the taking of a homestead to satisfy debt, and an 1879 law deferred the sale of foreclosed property unless it brought at least two-thirds of its appraised value and allowed redemption within one year of sale. These conditions made lenders reluctant to deal with farmers, and those who did felt justified in charging high rates of interest for their risk, a practice dubbed by farmers as “anaconda mortgages” because of their having to pledge the following year’s crops in order to obtain the current year’s supplies, which they felt was squeezing the life out of them. This shared victimization led to the formation of agrarian unions, beginning in the late 1860s and continuing into the twentieth century, for the purposes of advancing their social, educational, economic, and political interests.

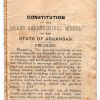

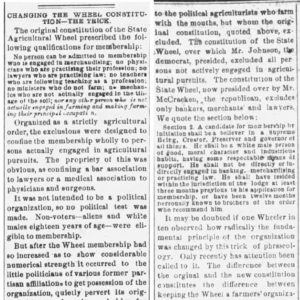

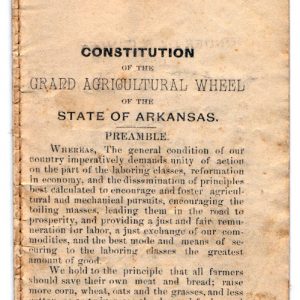

Among the many unions to emerge from this shared experience was the Agricultural Wheel, which originated at a meeting of farmers on February 15, 1882, arranged by William A. Suit and W. Taylor McBee, at McBee’s log schoolhouse, located eight miles southwest of Des Arc (Prairie County). The nine men who met there were small farmers, two of whom were from nearby Lonoke County. They agreed to form a farmers’ club, called the Wattensas Farmers’ Club. These men had the same concerns of other small farmers: the tenant system, political corruption, and a marketing system that forced farmers to sell their products at low prices while others resold them for much more. According to its constitution, the club’s purpose was “the improvement of its members in the theory and practice of agriculture and the dissemination of knowledge relative to rural and farming affairs.” The farmers elected William W. Tedford and McBee as president and secretary of the club, respectively. Four weeks after its founding, the farmers decided to change the name of the club to the Agricultural Wheel, in reference to agriculture as the “great wheel or power that controls the entire machinery of the world’s industries,” in the words of William Tedford, as well as the rings, especially political rings, that the farmers saw surrounding them. The Wheel was later incorporated as a statewide organization on April 9, 1883, with a membership of 500 and E. R. McPherson as state president.

The Wheel’s original emphasis was to improve its members’ economic situation through cooperative buying, the teaching of progressive farming methods, and working for the elimination of the one-crop system and anaconda mortgages. The Wheel was also committed to ending the business and banking monopolies that oppressed them, as they viewed it. Some members of the Wheel saw political action as a means of achieving those goals, and in 1884, local Wheels ran candidates in several counties and won some offices in Prairie and White counties.

The Wheel grew quickly; by October 1885, it had 462 subordinate, or local, Wheels in Arkansas, ten in Alabama, three in Mississippi, and four in Texas. On October 15, the Arkansas Wheel met at Greenbrier (Faulkner County) for the purpose of merging with the northwest Arkansas farmers’ union, the Brothers of Freedom. Isaac McCracken, president of the Brothers of Freedom, became the head of the merged organization. The Brothers had always turned to politics as a means of obtaining their objectives, and in the merger, Isaac McCracken influenced the Wheel to do the same. Some Wheelers disagreed with this move and left the organization rather than politicize it. (Many members identified themselves as Democrats and were sensitive to their depiction in Democratic newspapers as a tool of the Republican Party.)

The state Wheel met at Litchfield (Jackson County) on July 28, 1886, for the purpose of creating a national organization. Isaac McCracken was elected president of the national group, with C. A. Stuart as vice president and R. H. Morehead as secretary. The Wheel members also decided to drop the word “white” from their membership requirements and to provide for separate African American Wheels, if the various state Wheels wanted them. The admission of Black farmers was an indication that the white Wheel members recognized that Black farmers shared the same economic and social problems as white farmers. The following year, a Black farmers’ union called The Sons of the Agricultural Star, established in Monroe County in 1885, became part of the Wheel.

The Wheel’s first venture into statewide politics in 1886 was unsuccessful, as most of those candidates, being members of the Democratic Party, did not want to cut themselves off from the party by accepting the nomination of an independent party. The Wheel managed to put together a partial state ticket at its annual convention, which included the nomination of Charles E. Cunningham, a former Greenback Party member, for governor. This nomination actually violated the Wheel’s constitution, which prohibited partisan activity. As a result, many members protested the move and vowed not to do so again. Cunningham finished third in the election, far behind both the Democrat Simon P. Hughes and the Republican Lafayette Gregg.

The Wheel’s next venture into politics occurred in 1888, when it joined forces with the Knights of Labor to form the Union Labor Party of Arkansas. McCracken became the leader of the party. He had represented the state Wheel at the National Agricultural and Labor Congress in 1887, which had formed the National Union Labor Party. The state party nominated a full slate of candidates for state and federal office, including former state senator and one-legged Confederate veteran Charles M. Norwood for governor and Lewis P. Featherstone and McCracken for Congress in the First and Fourth Congressional districts, respectively. However, the state convention of the Wheel, meeting in Little Rock in July, declined to endorse Norwood for governor, though the state Republican Party did, after declining to nominate its own candidate. Norwood lost the governorship to the Democrat James P. Eagle by a vote of 99,214 to 84,213, in an election that was marked by fraud and violence. Featherstone originally lost his own race but was later awarded the First Congressional District seat after a House investigation ruled that fraud played a large role in his loss.

The 1888 elections marked the high point of the agrarian movement in Arkansas. In 1889, the national Wheel met at Birmingham, Alabama, where it voted to merge with the National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union of America, with Evan Jones of the Alliance as president and Isaac McCracken as vice president. As part of the merger agreement, Black farmers were now denied membership, thus eliminating almost half of all Southern farmers from its organization. This merger also marked the end of the Agricultural Wheel as an independent group.

The Arkansas Agricultural Wheel reached a peak membership by 1888 of 1,947 subordinate Wheels representing every county in the state, for a total of over 75,000 members. Although the Agricultural Wheel failed to gain much for farmers in Arkansas’s political arena, the group made a big difference in the lives of Arkansas farmers, both socially and economically. The local monthly meetings broke the monotony of farm work and made the previously isolated farmers feel that they were an important part of society. The meetings also had programs on literary topics and on the issues that affected farmers in politics. The Wheel also sponsored educational programs to help farmers achieve a higher level of productivity.

The National Farmers’ Alliance lost its influence among the farmers as the Populist Party and later the national Democratic Party adopted the agrarian platform as their own. It is estimated that the Farmers’ Alliance lost seventy-five percent of its membership on both the state and national levels by late 1891. Eventually the farmers who had joined agrarian groups like the Agricultural Wheel resumed their previous affiliation with the Democratic Party in Arkansas.

For additional information:

Ball, David B. “The Perils of Politics: The Agricultural Wheel in Arkansas, 1882–1885.” BA thesis, Princeton University, 1992.

Bayliss, Garland E. “Public Affairs in Arkansas, 1874–1896.” PhD diss., University of Texas, 1972.

Chess, Edward. “Agrarian and Labor Unions in Arkansas from 1870 to the Union Control Legislation of the 1940s.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1996.

Elkins, Francis Clark. “The Agricultural Wheel in Arkansas.” PhD diss., Syracuse University, 1953.

———. “The Agricultural Wheel in Arkansas, 1887.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 40 (Autumn 1981): 249–260.

———. “The Agricultural Wheel: County Politics and Consolidation.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Summer 1970): 152–175.

———. “State Politics and the Agricultural Wheel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Autumn 1979): 248–258.

Hild, Matthew. Arkansas’s Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018.

———. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

McCollom, Jason. “The Agricultural Wheel, the Union Labor Party, and the 1889 Arkansas Legislature.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Summer 2009): 157–175.

Morgan, W. Scott. History of the Wheel and Alliance and the Impending Revolution. Fort Scott, KS: J.H. Rice and Sons, 1889.

Paisley, Clifton. “The Political Wheelers and Arkansas’ Election of 1888.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Spring 1966): 3–21.

Saloutos, Theodore. “The Agricultural Wheel in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 2 (Summer 1943): 127–140.

Edward J. Chess

Pulaski Technical College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.