calsfoundation@cals.org

University of Arkansas

aka: University of Arkansas, Fayetteville (UA)

The University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) is located in the northwest corner of the state. It is Arkansas’s land grant university and is famed for its traditions, including the unique Razorback mascot. The institution was originally named Arkansas Industrial University but changed in 1899 to the University of Arkansas, reflecting its broader academic scope. It has long been an academic and cultural mainstay in Arkansas, with its research generating a great deal of economic progress for the state and its Razorback athletic program being arguably the state’s most popular.

UA’s Founding

The U.S. Congress passed the Morrill Land Grant Act in 1862, allowing 30,000 acres of public lands to be sold in each state to supply funds for a perpetual endowment. This fund would provide support for each state’s college of agriculture and the “mechanical arts,” or engineering.

While the legislature of Union-occupied Arkansas accepted the terms of the Morrill Act in 1864, the Civil War and Reconstruction delayed further action until 1868. At that time, an act was passed by the Arkansas General Assembly “establishing an Industrial University,” and on March 27, 1871, the legislature empowered the board of trustees to seek a location for the school.

Competitive bids were accepted from towns expressing an interest in being the location of the school. Elections for bond issues were held in Independence, Pulaski, and Washington counties. Washington County, like most of Arkansas still in post-war financial straits, voted $100,000 in thirty-year bonds, with the town of Fayetteville offering $30,000 to start the school, more money than the Prairie Grove/Viney Grove area, also in Washington County.

Fayetteville was already noted as a center of education, being the location of such institutions as the antebellum Arkansas College and the Fayetteville Female Seminary. William S. Campbell, in his history of Fayetteville, notes: “On the basis of compliance with provisions of the enabling act, solvency of bids, healthfulness of location, amounts tendered, and educational achievements, the bid was awarded to Fayetteville.”

In October 1871, Fayetteville officially won the bid, but in order to comply with the deadline of the Morrill Act ten years previous, the school had to open by February of 1872. The board selected the property for the campus in November 1871. A farmhouse on the McIlroy farm about a mile northwest of downtown Fayetteville was fitted with seats, blackboards, and stoves. It opened its doors to students as Arkansas Industrial University on January 22, 1872. Of the eight students at the new university, one was a woman, Anna Putman, reflecting local attitudes in the tradition of the famed Fayetteville Female Seminary at a time when women had little schooling of any kind. UA began and remained a coeducational institution.

An African American student, James McGahee, was also present when the university opened in 1872. According to an 1873 newspaper article in the Little Rock Daily Republican, McGahee was studying for the ministry of the Episcopal Church. While the student, from Woodruff County, is generally believed to have been tutored privately by Noah Gates and did not actually integrate the student body, his presence set the stage for UA’s twentieth-century decision to enroll a Black student without litigation, the first major Southern public university to do so without litigation.

About a dozen books were donated for a library by local citizens, and Noah Gates was named the first president. The first three instructors were C. H. Leverette, teaching ancient languages and literature; Mary Gorton, teaching mathematics and literature, and Lu Stanard, an instructor in the training school. The latter was a high school for those who required their high school diploma before pursuing a college degree, as there were few public high schools in the state at the time.

Old Main and UA Traditions

A remarkable achievement of those early years was the construction of the building that stands today as the symbol of the university—Old Main. Its Second Empire architectural style, an elaborate Victorian design with French mansard roof and dormer windows, was modeled on a similar building (since destroyed) at the University of Illinois in Urbana. It was built by the Fayetteville firm of Mayes and Oliver under the watchful eye of Judge Lafayette Gregg, an influential Fayetteville resident who had campaigned vigorously to have his town chosen as the university site and who oversaw the construction of the 90,000-square-foot building to make sure it was done properly. Joseph Carter Corbin, an African American who was state superintendent of education, signed the construction contract for the building in 1873.

The building opened its doors in 1875 as University Hall, later often referred to as the Administration Building and soon to be called simply “Old Main” because it was the main building on campus and the place where most classes, administrative functions, and even some sleeping rooms were located. It was the largest building in the state at the time of its opening and withstood numerous fires which might have destroyed it had the building not been constructed with exceptionally thick brick walls. One of its two towers is slightly higher than the other, giving rise to several legends, including one holding that it was built that way to distinguish it slightly from the University of Illinois and another which claims that the north tower is higher because the contractor was a Northerner paying homage to the Union for winning the Civil War. No solid evidence exists of either.

After falling into disrepair and being closed in 1981, it was restored through a fundraising campaign and reopened in 1991. It is the oldest building on campus, one of the oldest in the state, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. Old Main houses the Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences and Giffels Auditorium. The Honors College moved from Old Main to Ozark Hall in 2013.

Subsequent to what was called the “Great Building Program of 1905,” there were a total of twenty-five completed buildings on campus by the year 1928. By the year 2005, the campus consisted of 130 buildings on 345 acres of land.

Along with research and academic achievements, UA is known nationwide for its mascot, the Razorback. In 1895, the students voted on cardinal red as the official school color, and UA athletes were then known as the Cardinals. But an impassioned speech changed the course of the school’s history. Arkansas football coach Hugo Bezdek was greeted by a crowd of excited students at the Fayetteville train station on October 30, 1909. The underdog UA team had scored a major victory on the road, defeating Louisiana State 16-0. Coach Bezdek shouted to the delighted crowd that their team had performed “like a wild band of Razorback hogs.” The crowd loved the comparison to Arkansas’s ferocious wild boar, with its ridged back and fierce fighting ability, and in 1910, the students voted for the official university mascot to be changed from the Cardinals to the Razorbacks.

Along with the rousing “University of Arkansas Fight Song” (“Hit that line, hit that line, keep on going, move that ball right down the field!”), is the school’s enthusiastic “Hog Call” (“Wooooooo, Pig! Sooie!”), which began when a group of farmers used it to cheer on the team in the 1920s.

The tradition of Senior Walk, unique among American universities, began when members of the 1905 graduating class wrote their names in the wet cement of the sidewalk. Subsequent graduating classes had their names engraved in the sidewalk. In the 1930s, classes graduating prior to 1904 had their names added. An invention developed by University Physical Plant employees in 1986 and called the “Sand Hog” was designed specifically for inscribing names in Senior Walk. As of 2020, the names of more than 200,000 UA graduates appear on Senior Walk, which stretches for miles.

UA Alumni and Faculty

Notable UA alumni include J. William Fulbright, who served as university president from 1939 to 1941 before going on to the U.S. Senate; E. Fay Jones, internationally renowned architect; Jerry Jones, owner of the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys; Pat Summerall, sportscaster and former NFL football player; and Donna Axum Whitworth, Miss America 1964. Gordon Morgan was the first African American faculty member, being hired in 1969.

Two former UA faculty members were married in Fayetteville and later resided in the White House: America’s forty-second president, Bill Clinton, who served from 1993 to 2001, and former first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, who was elected a U.S. senator from New York in 2000, served as secretary of state, and was a presidential candidate.

Among its points of pride is the fact that UA became the first major public university in the South to admit an African American student without litigation when Silas Hunt was admitted to the UA law school in 1948, though Hunt died of tuberculosis a year later, without obtaining his degree.

In order to meet its goal of serving the people of the state effectively through cooperative strength and combined resources, the University of Arkansas allied itself to Little Rock University (LRU) in 1969, creating the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UA Little Rock). In Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal College began in 1873 with Joseph Carter Corbin as president and was officially a branch of the Normal Department of the Arkansas Industrial University. A traditionally African-American school, it became University of Arkansas Pine Bluff (UAPB) in 1972. Other institutions joined the UA system through the years: the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) in 1911, University of Arkansas at Monticello (UAM) in 1971, Phillips Community College of the University of Arkansas (1996), UA Community College at Hope (1996), UA Community College at Batesville (1997), Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas (2001), UA Community College at Morrilton (2001), University of Arkansas at Fort Smith (2003) and the Clinton School of Public Service (2004).

Though state supported, the individual campuses of the University of Arkansas System are operationally separate and administered by the system headquarters in Little Rock. In addition, the UA System in 2014 launched eVersity, the state’s first online-only degree-granting program. Seven years later, UA acquired Grantham University, a private, for-profit online university based in Lenexa, Kansas, turning it into University of Arkansas Grantham. On May 26, 2022, trustees for UA approved shutting down eVersity and merging its operations with the University of Arkansas Grantham.

Present-day UA

The UA campus today offers more than 200 academic programs. There are fifteen fraternities and ten sororities, including Chi Omega which was founded at the University of Arkansas in 1895 and which claims to be the largest women’s fraternal organization in the world with 240,000 initiates at 172 college campuses.

In 2005, the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences held most of the majors at the University of Arkansas, at 38.3 percent, followed by the Sam M. Walton College of Business with 19.6 percent. In athletics, the University of Arkansas plays in Division I-A of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), competing in the Southeastern Conference. In 2005, UA successfully completed a fundraising campaign that raised more than $1 billion, including a $300,000,000 challenge grant from the Walton Family Foundation. Its mission statement summarizes today’s UA: “The University of Arkansas is a nationally competitive, student centered research university serving Arkansas and the world.” In 2011, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching classified UA as among the nation’s top research universities.

On November 16, 2022, the UA Board of Trustees unanimously selected as the new chancellor Charles Robinson II, who started work there as a professor in the history department, making him the first African American to head the state’s flagship campus.

Enrollment in the fall of 2023 was a record high of more than 32,000 students.

For additional information:

Campbell, W. S. 100 Years of Fayetteville, 1828–1928. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1928.

“If This Walk Could Talk: Reflections on 150 Years.” https://vimeo.com/674991990?ref=em-share&fbclid=IwAR2tIFPMP_mb8mSObX7VHoGDBjMST6pnOPp1yXZZoGyqI43MskesvWh6YS4 (accessed March 20, 2024).

Leflar, Robert Allen. The First 100 Years: Centennial History of the University of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1972.

Robinson, Charles F., II, and Lonnie R. Williams, eds. Remembrances in Black: Personal Perspectives of the African American Experience at the University of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010.

Simpson, Ethel C. Image and Reflection: A Pictorial History of the University of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Traditions and Spirit of the University of Arkansas. Fayetteville: Arkansas Alumni, n.d.

University of Arkansas. http://www.uark.edu (accessed March 20, 2024).

“The University of Arkansas at 150.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Summer 2021).

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Henry Alexander

Henry Alexander  Carnall Hall, UA

Carnall Hall, UA  Chi Omega Greek Theater

Chi Omega Greek Theater  Samuel Dellinger

Samuel Dellinger  Fayetteville WWI Memorial

Fayetteville WWI Memorial  Fulbright Statue

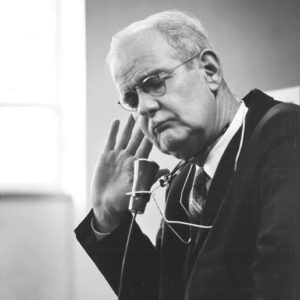

Fulbright Statue  Bill Fulbright

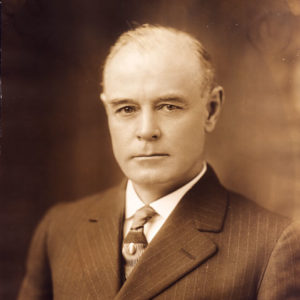

Bill Fulbright  John Futrall

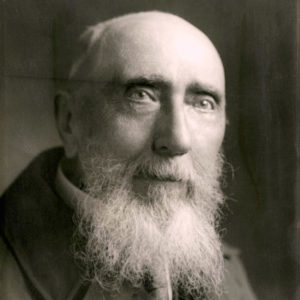

John Futrall  Noah Gates

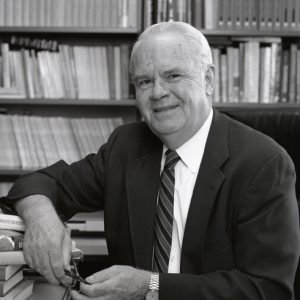

Noah Gates  Willard Gatewood

Willard Gatewood  Girls Dormitory

Girls Dormitory  Arthur Harding

Arthur Harding  Arthur Harding

Arthur Harding  Silas Hunt

Silas Hunt  Ben Kimpel

Ben Kimpel  Jay Lawhon

Jay Lawhon  Walter Lemke

Walter Lemke  Old Main Building, UA

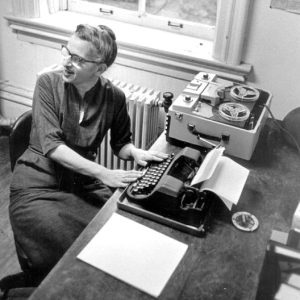

Old Main Building, UA  Mary Parler

Mary Parler  Peace Fountain

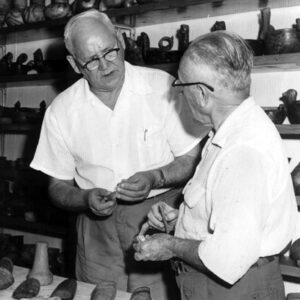

Peace Fountain  Albert Purdue

Albert Purdue  Razorback Stadium

Razorback Stadium  Razorback Stadium Dedication

Razorback Stadium Dedication  Nolan Richardson

Nolan Richardson  SATC Inductees

SATC Inductees  UA Aerial View

UA Aerial View  University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville  University of Arkansas's First Buildings

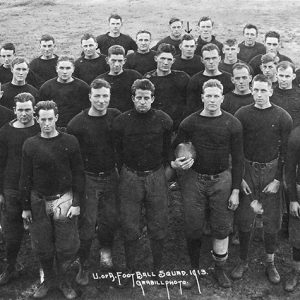

University of Arkansas's First Buildings  UA Football Team

UA Football Team  Vol Walker Library Dedication

Vol Walker Library Dedication  William J. Waggener

William J. Waggener

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.