calsfoundation@cals.org

Southwest Trail

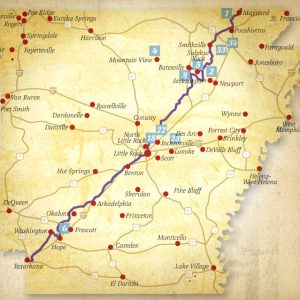

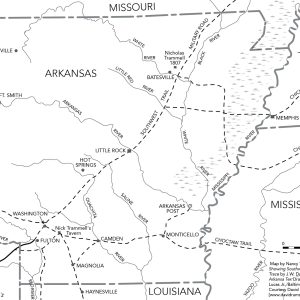

The Southwest Trail is a general term referring to a network of routes connecting the mid-Mississippi River Valley (the St. Louis-St. Genevieve area of Missouri) to the Red River valley (northeast Texas) in the nineteenth century. Most of the trail crossed Arkansas from northeast to southwest, entering at Hix’s Ferry (later Pitman’s Ferry) across the Current River in Randolph County and exiting at several crossings of the Red River south and west of Washington (Hempstead County). It followed the edge of the eastern terminus of the Ozark Plateau in northeast Arkansas and of the Ouachita Mountains in central and southwest Arkansas. The trail avoided the swamps, which covered much of eastern Arkansas, while skirting the foothills of the Ozarks and the Ouachitas. From Pitman’s Ferry to the Fulton (Hempstead County) crossing on the Red, the trail traversed 300 miles. Since most rivers and streams in Arkansas arise in the northern and western highlands and flow in a south and east direction, the Southwest Trail crossed the state perpendicular to these streams and their river traffic. Thus, travelers who chose not to move on the state’s many waterways found the Southwest Trail especially appealing.

It is not known when the term “Southwest Trail” was first used. The phrase appears to be largely a twentieth-century term. Nineteenth-century travelers referred to the trail by different names, including Arkansas Road, National Road, U.S. Road, Military Road, Natchitoches Trace, and Red River Road. Native Americans likely used the trail long before the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The Hernando de Soto expedition may have traveled parts of the route as early as 1541. After the Louisiana Purchase, the trail’s history can be divided into approximate periods.

Louisiana Purchase to Early Statehood

After the Louisiana Purchase, Americans began to trickle into Arkansas. The route was no more than a foot or horse path until 1819, when Arkansas became a territory. That year, the St. Louis Republican reported that 100 people a day passed through St. Charles, Missouri, a third of whom passed south into Arkansas, distributing themselves along the trail all the way to the Red River in southwest Arkansas. The first wave of immigration to Texas occurred in the 1820s, and wagon trains along the trail were common. In 1826, traveler Joseph Meetch, upon reaching the Little Red River north of modern-day Searcy (White County), reported, “Here I passed six wagons and carts loaded with store goods, and movers going on to Big Red River. The store goods was from Kaskasky (Kaskaskia, Illinois), and the movers was from the state of Missouri.” Arkansas Gazette editor William Woodruff frequently mentioned the wagon trains passing through Little Rock (Pulaski County) on their way to the Red River region. By 1830, the territory’s population was nearly 30,000. An estimated four-fifths of the new arrivals came after 1817 by way of the Southwest Trail.

During Arkansas’s territorial period, the only towns on the trail were Jackson (Randolph County), Little Rock, and Washington. Davidsonville (Randolph County) was not on the most-used route, and this contributed to the early town’s decline. When historians refer to the “Southwest Trail,” they usually mean the territorial period road when it was one of the state’s few roads.

Military Road is a more precise route for the trail. In the 1830s, during President Andrew Jackson’s administration, Congress attached funding to military appropriations bills that provided for improvements to the road. Army Lieutenant Richard D. Collins surveyed the route and oversaw construction contracts. Improvements included cutting and pulling stumps, building bridges, and, in some cases, leveling the road and digging ditches. The Military Road was a single roadbed, whereas the Southwest Trail was a network of routes. Arkansas has several “military roads,” including the well-known Memphis to Little Rock Military Road. The route which paralleled the Southwest Trail was prominently labeled by early surveyors as “Military Road.” Benton (Saline County) and Rockport (Hot Spring County) were on the Military Road. Batesville (Independence County), Arkadelphia (Clark County), and Hot Springs (Garland County) were not on the Military Road, although they were stops for some travelers on the Southwest Trail.

Along the trail came preachers. The first Methodist church in Arkansas, Henry’s Chapel, was built a few miles northwest of Washington in 1817 at a place called Mound Prairie. The first Baptist church in Arkansas, Salem Church, was built in 1818 at what became Columbia (Randolph County). They also were the first churches along the Southwest Trail.

Geologist George W. Featherstonhaugh, in his Excursion through the Slave States, from Washington on the Potomac to the Frontier of Mexico; With Sketches of Popular Manners and Geological Notices (originally published in 1844), described his travels down the Southwest Trail/Military Road in 1834. As he neared Arkansas from Missouri, Featherstonhaugh was happy to learn that a Military Road had recently been cut through Arkansas: “Entering upon it, we found the trees had been razed close to the ground, and that the road was distinguished by blazes cut into some of the trees standing on the roadside so that it could not be mistaken; a great comfort to travelers in such a wilderness.” After crossing the White River below Batesville, Featherstonhaugh found the trail so steep that he had to empty his wagon at the bottom of White River Mountain so the horse could pull it to the top.

Featherstonhaugh observed that, in Arkansas and Missouri,

If a tree is blown down near a settler’s house and obstructs the road, he never cuts a log out of it to open a passage; it is not in his way, and travelers can do as they please, because nobody would prevent their cutting it. But travelers, feeling no inclination to do what they think is not their business, never do it…. Often when a track is established round the first fallen tree another obstruction shuts up this track, and so in a long period of time the established track gets removed into the woods, far out of sight of the settler’s house…. These circuitous tracks are known by the name turn-outs, and if you are inquiring towards evening how many miles it is to the next settlement, you perhaps will be told, “16 miles and a heap of turn-outs.” We once made a calculation that these turn-outs had added at least five miles to our journey in Missouri and Arkansas.

Travelers on the trail usually spent the night in a settler’s home. Homes ranged from a dirt-floor log cabin to Jacob Barkman’s brick house near Arkadelphia. Because there were no restaurants or hotels in the modern sense, frontier settlers who lived along the trail often provided travelers room, a meal, and livestock feed for a fee. Accommodations and meal quality varied widely. Businessman and farmer William Wyatt noted in his 1836 travel diary that fees for room and board for one night generally ranged from seventy-five cents to $1.25 per traveler.

Because there were few towns along the early trail, most travelers noted distances from stream to stream because streams were easy reference points and because they were hazardous to cross, especially in the spring; drownings and lost property were common.

Early Statehood to Reconstruction

As towns such as Batesville and Searcy grew, the trail was rerouted to match the growth of these local population centers. Steamboats allowed some travelers to skip parts of the trail. During this era, a higher percentage of those accessing the trail did so by the Memphis to Little Rock route before heading southwest along the trail. North of the Arkansas River, much of the Military Road bed was abandoned, and Civil War officers referred to Military Road as “Old.” South of the Arkansas, much of the trail remained in the Military Road bed for decades.

Reconstruction to Modern Era

The St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern Railway (originally the Cairo and Fulton Railroad) was built across Arkansas, paralleling the Southwest Trail, in the 1870s. As railroads were built, steamboats became less important. The trail known to travelers in the 1830s exists today in some places as modern roads and as wagon ruts in the forest. Two easily accessible places where modern roads follow the old trail are Old Stage Coach Road in southern Pulaski County and Batesville Pike in northern Pulaski County. In other places, agriculture and urban sprawl have obliterated the trail. In a sense, there is still a Southwest Trail. Interstate 30 and U.S. Highway 67 parallel the route for automobile traffic, and the old St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway is today a part of the Union Pacific Railroad system.

For additional information:

Featherstonhaugh, George W. Excursion through the Slave States, From Washington on the Potomac to the Frontier of Mexico; with Sketches of Popular Manners and Geological Notices. New York: Negro Universities Press, 1968.

Medearis, Mary. Washington, Arkansas: History on the Southwest Trail. Rev. ed. Hope, AR: Etter Printing Company, 1984.

Scott Akridge

White County Historical Society

Arkansas Heritage Trails System

Arkansas Heritage Trails System Transportation

Transportation de Soto, Hernando

de Soto, Hernando Jacob Barkman

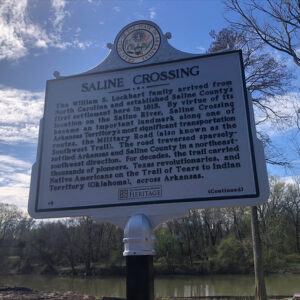

Jacob Barkman  Saline Crossing Plaque

Saline Crossing Plaque  Southwest Trail

Southwest Trail  Southwest Trail

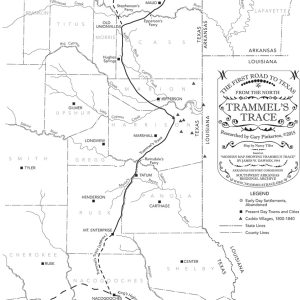

Southwest Trail  Trammel's Trace

Trammel's Trace

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.