calsfoundation@cals.org

Pottery

Pottery has been produced in Arkansas from prehistoric times up to the present day. Of note are prehistoric Native American wares from the Woodland Period beginning 2,500 years ago and the prehistoric and historic Caddo pottery tradition that flourished from AD 800 to 1660. Commercial manufacturing and regional ware made by the Ouachita Pottery in Hot Springs (Garland County), the Hyten Pottery (later the Eagle Pottery) in Benton (Saline County), Camden Art and Tile Company in Camden (Ouachita County), and the Dryden Potteries, Inc., in Hot Springs have their roots in the American Art Pottery movement of the late nineteenth century and the American Craft movement of the early twentieth century. Smaller production studios evolved after the Korean War, and individual artists’ studios appear from World War II to the present. One of Arkansas’s natural resources is clay found in deposits that lie east of Interstate 30 from Arkadelphia (Clark County) to Little Rock (Pulaski County) and south of Interstate 40 from Little Rock to Memphis, Tennessee.

The Woodland Period marks the first widespread use of pottery across what is now Arkansas. The Plum Bayou culture, for instance, made a number of pottery containers, including conical jars; most items of daily use were undecorated, though a number of highly decorated pieces, likely employed in religious ceremonies, have been recovered. Mississippian Period pottery often displays a number of naturalistic images. In the case of head pots, the vessels were actually shaped like human heads. The Caddo, however, are said to have the finest pottery in “variety, quality, and artistic expression east of the Rocky Mountains.” Their prevalent forms were carinated bowls and bottles with long slender necks handsomely decorated with incised circle and scroll-like designs.

After the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, pottery manufactured in the United States began to compete with European-made ware. The rapid westward migration of skilled workers, the development of river and rail transportation, and the expanding market west of the Mississippi River made commerce viable. During the Reconstruction era when potteries and brickworks began, potters and businessmen exploited a rising demand for clay objects, and the state’s natural reserves of clay.

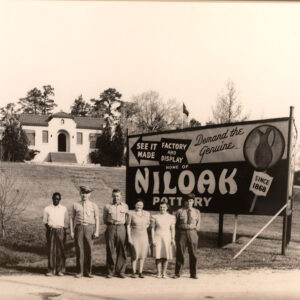

Commercial manufacturers of clay objects such as the Ouachita Pottery in Hot Springs and the Hyten Pottery (later named the Eagle Pottery) were founded after the Civil War. By 1909, John Hyten’s son Charles took over his father’s pottery and founded a second pottery, the Niloak Pottery Company in Benton, and produced Mission “swirl” ware during the waning years of the American Craftsmen movement (1916 to 1930s). Niloak’s popular and collectable Missionware consisted of wheel-thrown vessels fashioned with a swirl decoration of multicolored clays spiraling up the clay body. The factory’s zenith was reached in the late 1920s. By World War II, this pottery evolved into the Winburn Tile Manufacturing Company, based in Little Rock, manufacturers of kitchen and bathroom tiles. It went out of business on July 6, 2001.

Another major manufacturer was the Camden Art and Tile Pottery (1926–1986), using the trademark name “Camark.” It was an industrial project in Camden formed by a consortium of businessmen, potters, and the Camden Chamber of Commerce. Characteristic of Camark ware were wheel-thrown and slip-cast ware (ware made from molds) consisting of vessels decorated with a wide variety of iridescent and lustrous, brilliant and matte, plain and hand-painted glazes consistent with pottery of the American Art Pottery movement. The Dryden Pottery, which was founded in Kansas in 1946 and moved to Arkansas ten years later, manufactures useful modern ware and novelty items that are wheel thrown or slip cast.

Following the American Art Pottery and American craft movements—in which designers, potters, engineers, chemists, mold makers, and other specialty labor created objects in factories—came the studio craft movement. The latter movement has two divisions: first, the production studio where the clay objects are designed, executed, decorated, and marketed by an individual working in a studio environment; second, the studio craftsman who specializes in one-of-a-kind works.

Typically in production pottery, multiple objects are created using similar forms, techniques, and decorative motifs for easy market recognition. David Dahlstedt, a former thrower for Dryden Pottery, set up a studio at the Ozark Folk Center State Park in Mountain View (Stone County), where he and his wife, Becki, demonstrated wheel-throwing and ceramic decoration. The couple now operates an independent studio in Mountain View. Their tableware is characterized by either a thick, creamy, off-white glaze with blue brushwork decoration or by a rich, glossy, translucent brown with bursts of blue or green glaze. Another couple, Michael Haley and Susy Siegele, operates the Buzzard Mountain Pottery near Huntsville (Madison County). They employ several other potters as assistants and distribute work throughout the United States. The work is slab built, neither thrown nor slip cast. Instead, a technique inspired by Japanese ceramics is used: multicolored porcelain is extruded in predetermined shapes and bundled together in large blocks, which are then cut across the section to create the design. The design is the same on the outside as it is on the inside.

Among others who may be considered part of the American studio craft movement are three distinguished Arkansas studio potters: Rosemary Beryl Snook Fisher, Joe A. Bruhin, and Helen Phillips. Fisher was trained in traditional English pottery. She taught ceramics and had a studio in Little Rock. Bruhin runs the Fox Mountain Pottery in Fox (Stone County). His work, also inspired by Japanese techniques, is wood-fired in an anagama or a noborigama kiln. Phillips, a former teacher, works out of her studio in Bruno (Marion County) and is known for both functional and sculptural work.

For additional information:

Arkansas Arts Pottery Collection. Old State House Museum Online Collections. Pottery Collection (accessed April 12, 2022).

Cherry, James F. The Headpots of Northeast Arkansas and Southern Pemiscot County, Missouri. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Gifford, David Edwin. The Collector’s Encyclopedia of Niloak: A Reference and Value Guide. 2nd ed. Paducah, KY: Collector’s Books, 2001.

———. Collector’s Guide to Camark Pottery. 2 vols. Paducah, KY: Collector Books, 1997, 1999.

Hathcock, Roy. Ancient Indian Pottery of the Mississippi River Valley. Camden, AR: Hurley Press, Inc., 1976.

Alan Du Bois

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.