calsfoundation@cals.org

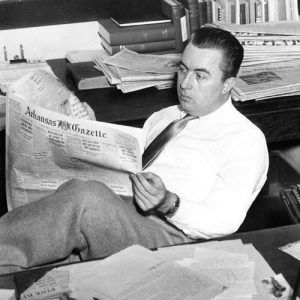

Harry Scott Ashmore (1916–1998)

Harry Scott Ashmore was the executive editor of the Arkansas Gazette during the 1957 desegregation crisis at Little Rock’s Central High School and wrote a series of Pulitzer Prize–winning editorials on the subject. His front-page calls for reason thrust him into the front lines of the escalating battle between civil rights and “states’ rights.”

Harry Ashmore was born on July 28, 1916, in Greenville, South Carolina, to William Green Ashmore and Nancy Elizabeth Scott. He was the younger of two sons. Ashmore’s father owned part interest in a shoe store in Greenville. The family lived a comfortable middle-class life until the early 1930s, when William Ashmore’s declining health, coupled with the Depression, left the family in relative poverty.

Ashmore attended Clemson Agricultural College, a state-supported school that had no tuition fees, and graduated with a degree in general science in 1937. At both Greenville High School and Clemson, Ashmore demonstrated exceptional writing skills, and he served as editor of both school newspapers. After graduation from college, he started his newspaper career as a reporter at the Greenville Piedmont. He later transferred to the Piedmont’s morning counterpart, the Greenville News.

On June 2, 1940, Ashmore married Barbara Edith Laier, a physical education teacher at Furman University in Greenville. He applied for a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University, one of the most prestigious honors for a journalist, and was accepted for the 1941–42 school year. World War II cut short Ashmore’s year at Harvard. He entered the service and became an operations officer assigned to the Ninety-fifth Infantry Division. The division saw heavy fighting as part of George Patton’s Third Army, and it became known as the “Iron Men of Metz” after they captured that French town.

After the war, Ashmore became the editorial writer for the Charlotte News of North Carolina. He caught the attention of John Netherland Heiskell, part owner of the Arkansas Gazette, during a presentation he made at a newspaper editors’ conference. Heiskell hired Ashmore as an editorial writer, and Ashmore joined the staff in September 1947. He quickly became the executive editor for the newspaper and added management of the newsroom to his duties. Ashmore gained a reputation as a moderate-to-liberal thinker and started to be recognized outside the state for his writing.

Governor Sidney Sanders McMath asked Ashmore to speak at the Southern Governors’ Conference when it met in Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1951. Ashmore spoke on civil rights, a previously taboo topic at the annual meeting. Newspapers across the country printed the speech or excerpts from it, and Ashmore became popular on the national speaking circuit.

Ashmore worked with Heiskell and Hugh Patterson, who managed the business side of the newspaper, to upgrade the Gazette and improve the newsroom. Ashmore’s reputation as a journalist attracted many aspiring newsmen who went on to have notable careers in journalism and publishing, such as Jerry Dhonau, Robert (Bob) Douglas, Charles Portis, Ray Moseley, Roy Reed, and William (Bill) Shelton.

Between the speaking circuit and running the editorial side of the newspaper, Ashmore found time to take on other projects. His first book, The Negro and the Schools (1954), was a report from a multi-year Ford Foundation research project on the disparate system of bi-racial education in the South. Advance copies of the report were given to members of the U.S. Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren later told Ashmore that the report was used as a source when the Court members were drafting the implementation decree for the Brown II decision in 1955.

During the 1954 gubernatorial election, incumbent Francis Cherry attempted to smear his opponent, Orval E. Faubus, by noting that Faubus had attended the socialist Commonwealth College at Mena (Polk County). At first, Faubus denied attending the school, but documentary evidence was provided. Ashmore was outraged that Cherry would use this tactic and threw his support to Faubus, ghostwriting a speech for him to explain the “misunderstanding.” The speech was a masterpiece of political rhetoric, with a mix of humility, charity, and artful dodging, and it is credited with saving Faubus’s political career. The grateful Faubus was elected governor and pledged his friendship to Ashmore.

Ashmore took a leave of absence from the Gazette in 1955 to join presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson’s campaign staff. Hired to be a press secretary, Ashmore soon became a key member of Stevenson’s team, helping to develop Stevenson’s platform for the campaign. He returned to the Gazette in July 1956.

W. W. Norton Company signed Ashmore to write a book based on his views of the changing social and political landscape in the South. He delivered the manuscript for Epitaph for Dixie in 1957, and it was published in January 1958, halfway through the turbulent school year during which Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County) was desegregated.

During the desegregation crisis, Ashmore worked behind the scenes with local moderates and behind the typewriter writing editorials to support compliance with the law requiring desegregation of the schools. The series of front-page editorials won a Pulitzer Prize in journalism. More important, the editorials positioned Ashmore as a public figure around whom racial moderates and liberals could rally. Ashmore also became the target of the segregationists’ criticism and hatred. His critics labeled him an interloper, and his name became synonymous with “carpetbagger.”

Ashmore’s editorials created a bitter feud with Faubus, his former ally. Faubus and the segregationists positioned Ashmore and the Gazette as the enemy at every opportunity and conducted a successful campaign to boycott the newspaper and intimidate its advertisers.

In 1959, the state legislature passed a resolution to change the name of Toad Suck Ferry near Conway (Faulkner County) to Ashmore Landing. Faubus vetoed the bill and said, “In my judgment, many people of the state would consider the renaming of the Ferry as an act that would defame a well known landing by naming it for a man regarded by many as the state’s greatest renegade since Powell Clayton.”

Ashmore left the Gazette in 1959 to join the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara, California, a political think-tank headed by Robert Maynard Hutchins. Concurrently, he served as the editor-in-chief of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and divided his time between Santa Barbara and Chicago, Illinois. Ashmore wrote eight more books, including Arkansas: A Bicentennial History (1978).

He continued to write, speak, and act as a consultant in the areas of journalism and civil rights until his death on January 20, 1998. He was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at sea off the coast of Santa Barbara.

For additional information:

Ashmore, Harry S. Civil Rights and Wrongs: A Memoir of Race and Politics 1944–1996. Rev. ed. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997.

———. An Epitaph for Dixie. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1958.

Harry S. Ashmore Papers, 1947–1961. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Sawyer, Nathania K. “Harry S. Ashmore: On the Way to Everywhere.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2001.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Nathania Sawyer

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.