calsfoundation@cals.org

Harrison (Boone County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36º13’47″N 093º06’27″W |

| Elevation: | 1,182 feet |

| Area: | 11.20 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 13,069 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | March 1, 1876 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

582 |

1,438 |

1,551 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,602 |

3,477 |

3,626 |

4,238 |

5,542 |

6,580 |

7,239 |

9,567 |

9,922 |

12,152 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

12,943 |

13,069 |

Located in the Ozark Mountains of north Arkansas, Harrison is a hub of regional tourism and industry. The town struggles, however, to overcome the national attention focused on it due to racial conflicts in the early 1900s and the reappearance of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1990s.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Before white settlers arrived to settle the area that would become Harrison, the Osage called the area home. The Cherokee arrived during the Trail of Tears. The Benge Route was north of the present city of Harrison. With the arrival of white settlers by the 1830s, the Osage and Cherokee were forced out of the area.

Named after the creek that continues to run through the county, Crooked Creek Post Office was established in 1836 and managed by the first postmaster, Joseph Hickman. Stiffler Spring was named after the land’s owner, Albert Stiffler. These two settlements were later joined with the creation of Harrison.

A part of Carroll County at the time, Crooked Creek and Stiffler Spring grew. More residents, many from Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, arrived seeking farmland.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The Civil War devastated the area. Union and Confederate sympathies divided families. Within Crooked Creek valley, homes and businesses were destroyed. The end of the war failed to alleviate political differences. Union and Confederate tensions resulted in a split in Carroll County, with Union-leaning Boone County being formed from the eastern portion of Carroll County in 1869.

Justice was upheld in the log store of Captain Henry W. Fick near Stiffler Spring. Fick was also appointed postmaster. The first paper, The Boon(e) County Advocate, was started by Thomas Newman and published in 1870. In 1873, the Harrison Highlander was published by Newman. The name changed to the Harrison Times in 1876. The Harrison Times became the Harrison Daily Times in 1919, but had a weekly edition in addition to the daily until 1937. The first school in Harrison was established in the 1860s on land donated by Captain Fick.

Determined to create a new town as the county seat, Fick had Colonel Marcus LaRue Harrison lay out the town with wide side streets and a courthouse square. Harrison and crew were in the area surveying for the railroad. In exchange for the survey, Fick named the town after the surveyor. In 1870, Crooked Creek Post Office was renamed Harrison. Newspaper editor Thomas Newman was elected mayor in 1882. The U.S. Government Land Office moved to town in 1871.

Harrison experienced opposition to its position as county seat. Civil War sentiment drove the Democratic, Confederate-leaning residents of Bellefonte to challenge the Republican, Union-leaning residents of Harrison for the designation of county seat. A hard-fought election ensued. Newspapers carried reports of murder attempts and corruption. Muskets were rumored to have been slipped into Harrison in boxes marked “Records.” However, a countywide vote resulted in Harrison winning the position of county seat.

Post Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

In 1880, a wagon train left Harrison to find a larger market for the area’s cotton, wheat, and produce, and to obtain a commitment from the state to build a road to connect Harrison and Russellville (Pope County). Celebrations to welcome the wagon train were held in Russellville and Little Rock (Pulaski County). The celebration in Russellville included Governor William R. Miller. The train continued on to Little Rock for a feast. Although a proposal to build a railroad between Harrison and Russellville was made as a result of the trip, lack of funding prevented the proposed construction.

William Arterberry, an accused arsonist, was shot to death by a mob at Harrison on October 22, 1880. On November 11, 1886, a white man named Andrew Mullican was taken from the jail in Harrison and lynched outside of town.

By 1890, one of the four high schools in the county was located in Harrison. The others were in Rally Hill, Bellefonte, and Valley Springs.

The 1900s brought rapid change to Harrison. The Harrison Electric and Ice Company provided the first electricity in 1901. In 1900, telephone lines connected the town to communities as far away as Eureka Springs (Carroll County) and Marshall (Searcy County). By 1905, 175 miles of lines and 435 telephones had been installed.

The St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad arrived on March 22, 1901. By 1912, the headquarters of the Missouri and North Arkansas (M&NA) line was located in Harrison. Financial problems led to reduced wages. A strike by employees hit the line in 1921. Conflicts between those on strike and strike breakers resulted in harassment and vandalism. The Protective League was established to prevent further damage and destruction. The line closed, then was reopened with lower wages. Bridges were burned. The Protective League administered its form of justice with whippings and the hanging of Ed Gregor during what is now called the Harrison Railroad Riot. Membership in the Protective League overlapped with membership in the Ku Klux Klan, the local chapter of which was formally organized the following year. The M&NA was granted permission to stop service in 1961.

Harrison has also been the site of tremendous racial violence. In 1905, an African American seeking shelter broke into a house and was jailed for the break-in. A vigilante mob subsequently went to the jail and whipped the man and another black prisoner. The men were ordered to leave town. The mob burned homes and whipped residents as it moved through the black section of town. Many black residents fled the city. The remainder of the black community left amid another race riot after the 1909 trial of Charles Stinnett, who was accused of raping an elderly white woman. His conviction and hanging resulted in making Harrison a “sundown town.”

In the early 1920s, with the public school in danger of closing due to insufficient funds, the Mother’s Club was formed. The group collected money for the school, bought supplies, paid a teacher’s salary, and paid tuition for children unable to pay.

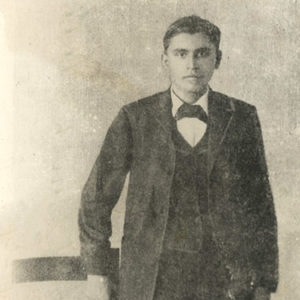

The death of outlaw Henry Starr took place in Harrison in 1921 and created national interest. Starr and accomplices attempted to rob the People’s National Bank on February 18. The attempt ended when former bank president W. J. Myer took a shotgun from the bank vault and fired, wounding Starr, who died four days later in the county jail.

During the Depression, foreclosures took farms and businesses. The proposal for a hospital was defeated in a city-wide vote. Area residents served in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps. By the end of the Depression, all the banks that had existed were gone.

World War II through the Faubus Era

In the 1950s, Harrison was growing. It won top honors twice in the Arkansas Community Accomplishment Contest, and tourism began to play a big part in the economy. J. E. Dunlap of the Harrison Daily Times declared the city the “hub of the Ozarks” due to its easy access to Bull Shoals Lake, Norfork Lake, Table Rock Lake, and Lake Taneycomo. Industries also played a role in Harrison’s growth. In the late 1950s, Oberman Manufacturing Co. and Harrison Furniture and Frames Co. began operating in the city. The name of Harrison Furniture and Frames was changed to Flexsteel Industries in 1958; in 2019, it was announced that Flexsteel would be closing its Harrison plant.

Although Crooked Creek flooded periodically, the flood of May 7, 1961, did the most damage. Twelve feet of water flooded the south side of the square, and four people were killed.

A native of Harrison, John Paul Hammerschmidt, was elected congressman for the Third Congressional District in 1966. He held the seat for twenty-four years.

Modern Era

S-C Seasoning Company, Inc., began operation in Harrison in 1971. The family-owned company makes Cavender’s All Purpose Greek Seasoning, a seasoning sold internationally.

On November 6, 1973, a county-wide vote approved a tax for the creation of a college. North Arkansas Community College was built in Harrison. It later changed its name to North Arkansas College.

The designation of the Buffalo River as a National River drew attention to the area. Harrison benefitted from increased tourism and the selection of the city as the site of the headquarters for the Buffalo River.

The city grew steadily throughout the last half of the twentieth century. Between 1990 and 2000, the population of the city increased from 9,922 to 12,152—then increased again by the 2010 census to 12,943. The increase consisted of retirees and employees working in Harrison, the economic center of Boone County.

Although the practice of not providing services to African Americans ended in the 1970s, the stigma Harrison earned as a sundown town was reinforced by the reappearance of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in the early 1990s. Klan rallies, led by local resident Thom Robb, ceased in the mid-1990s although the Klan maintains a compound outside nearby Zinc and a presence on the Internet, and Robb continues to send letters to the local paper. Incidents of racial slurs have been reported against black students on opposing athletic teams playing in Harrison. In a 2003 editorial, the Harrison Daily Times challenged community, political, business, and religious leaders to work to change the town’s image. However, Harrison’s struggle with its image made national news after the October 15, 2013, erection of a billboard reading, “Anti-Racist Is a Code Word for Anti-White.” It remains unknown who paid for the billboard. A second controversial billboard soon followed; this one read, “Welcome to Harrison. Beautiful Town. Beautiful People. No wrong exits. No bad neighborhoods.” Members of the community protested, and the Harrison Community Task Force on Race Relations, which was formed in 2003, paid for its own billboard a few months later; this one stated, “Love your neighbor,” and featured a quotation from Martin Luther King Jr. On April 1, 2014, the task force and the Arkansas Martin Luther King Jr. Commission held a community event at which they buried a coffin symbolizing racism. In December 2014, Harrison again attracted wide attention after the Ku Klux Klan paid for a billboard advertising its online radio station.

Tourism continues to contribute to the city’s economy as tourists travel to the surrounding lakes, the Buffalo River, and nearby Branson, Missouri. A variety of festivals are held in the city, including Harvest Homecoming, the Blue Grass Festival, and Crawdad Days.

Modern-day Harrison is far different from how it was in the past. A levee along Crooked Creek protects downtown from flooding. The old high school houses the Boone County Historical and Railroad Society, which displays three floors of city and county history. The Brandon Burlsworth Youth Center serves children and adults. The Ozark Arts Council purchased the 1929 Lyric Theatre in 1999, and plays, classic movies, art shows, and concerts are presented in the historic building. In 2011, the first liquor store to operate in Harrison since 1941 opened its doors, following an election that turned the county wet.

Notable Figures

Harrison has been home to several notable figures, including country musician and public servant Hugh Ashley; football player Brandon Burlsworth, after whom the Brandon Burlsworth Foundation was named; football star and businessman William Richard (Bill) Phillips; and Claude H. Turney, who established Turney Wood Products, Inc. Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Vance Trimble was born in Harrison. Ida Callery, a suffragist, was raised in Harrison. Alexander Hull was the state’s sixteenth secretary of state. Jack Williams received a posthumous Medal of Honor for service during World War II.

Attractions

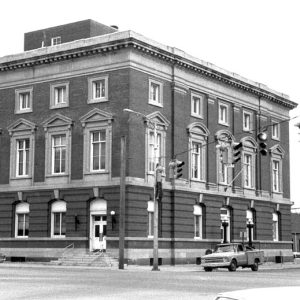

The Boone County Courthouse was built in 1909 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, as is the Twelve Oaks estate, erected in 1922. The Lyric Theater is a local venue for concerts and plays. The Boone County Regional Airport is a few miles outside of town.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks R. “The Strike and the Still: Anti-Radical Violence and the Ku Klux Klan in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Winter 1993): 405–425.

Boone County Historical and Railroad Society. History of Boone County. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Co., 1998.

Froelich, Jacqueline. “Race, History, and Memory in Harrison, Arkansas: An Ozarks Town Reckons with Its Past.” In Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives, edited by John A. Kirk. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Froelich, Jacqueline, and David Zimmerman. “Total Eclipse: The Destruction of the African American Community of Harrison, Arkansas, in 1905 and 1909.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Summer 1999): 133–159.

Hanley, Ray, and Diane Hanley. The Postcard History Series: Carroll and Boone County, Arkansas. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publishing, 1999.

Rea, Ralph R. Boone County and Its People. Van Buren, AR: Press-Argus, 1955.

C. J. Miller

Springdale, Arkansas

1961 Flood

1961 Flood  Baker Prairie Natural Area

Baker Prairie Natural Area  Boone County Courthouse

Boone County Courthouse  Boone County Courthouse

Boone County Courthouse  Boone County Heritage Museum

Boone County Heritage Museum  Boone County Map

Boone County Map  Connerley Hotel

Connerley Hotel  Harrison

Harrison  Harrison Bridge

Harrison Bridge  Harrison U.S. Courthouse

Harrison U.S. Courthouse  Harrison Courthouse Square

Harrison Courthouse Square  Harrison First Passenger Train

Harrison First Passenger Train  Harrison Flood

Harrison Flood  Harrison Government Building

Harrison Government Building  Harrison Grammar School

Harrison Grammar School  Harrison Overlook

Harrison Overlook  Harrison Roads

Harrison Roads  Harrison Roundhouse

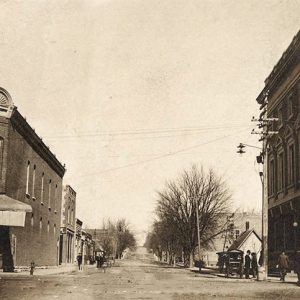

Harrison Roundhouse  Harrison Street Scene

Harrison Street Scene  Harrison Street Scene

Harrison Street Scene  Harrison Street Scene

Harrison Street Scene  Harrison Street Scene

Harrison Street Scene  Harrison Street Scene

Harrison Street Scene  Harrison Times

Harrison Times  Harrison Town Square

Harrison Town Square  Harrison View

Harrison View  Harrison Welcome Center

Harrison Welcome Center  Hillcrest Home

Hillcrest Home  Holiday Inn of America

Holiday Inn of America  Hotel Seville

Hotel Seville  Joe's Bar-B-Q

Joe's Bar-B-Q  Lyric Theater

Lyric Theater  Marine Corps Legacy Museum

Marine Corps Legacy Museum  Mountain Meadows Massacre Monument

Mountain Meadows Massacre Monument  Mystic Caverns

Mystic Caverns  North Arkansas College

North Arkansas College  Railway Workers

Railway Workers  Sorghum Mill

Sorghum Mill  Henry Starr

Henry Starr  Turney Wood Products Plant

Turney Wood Products Plant  Willow Street

Willow Street

The Goblin is Harrison’s high school mascot, one of the most unusual in the country. http://harrisonhslibrary.weebly.com/history-of-the-goblin.

Although I was born and raised in Hawthorne, Nevada, my uncle Jeffrey B. Wallace left there in the early forties with the WPA. My father Aubury C Wallis and mother Martha B Jones/Wallis left there in the late forties for Kansas and in the early fifties for Nevada from Yardelle. We made almost yearly vacation trips to see our relatives there. Born in 1955, I remember the devastating 1961 flood and love the pictures of the Boone County courthouse where we would go and sit and whittle cedar on the benches out in front of it. It was in the later sixties that I bought my first deer hunting rifle at Miller’s Dry Goods. Thank you for the article and all the history. Always enjoyed the trips back to where my parents were raised.