calsfoundation@cals.org

Guy Hamilton "Mutt" Jones (1911–1986)

Guy Hamilton “Mutt” Jones was a lawyer and politician who became one of the most influential state lawmakers of the post–World War II era. Jones served nearly twenty-four years in the state Senate representing Faulkner County and, at various times, five other counties in north-central Arkansas.

“Mutt” Jones was born on June 29, 1911, in Conway (Faulkner County), the youngest of nine children of Charles C. Jones and Cora Henry Jones. His father was a country schoolteacher and later operated a motel in Conway. Jones was short, barely exceeding five feet when he was grown. His stature made him feel inferior until a teacher told him that he spoke exceedingly well and should try debating. He became a champion debater, finishing second in the state debate contest in 1928, and his inferiority complex vanished, though his stature earned him the lifelong sobriquet of “Mutt.”

In the depths of the Great Depression, Jones managed to go to Hendrix College, graduating in 1932. He taught at Joe T. Robinson High School west of Little Rock (Pulaski County) for two years and briefly at the state vocational training school at Clinton (Van Buren County). He became a co-owner of a service station and, at night, attended law classes at what is now the University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law. He passed the bar in 1935, understudied with a Conway lawyer, and started his own practice in 1937. In 1941, he married Elizabeth Relya of Almyra (Arkansas County). They had two sons.

Drafted into the army in 1942, Jones served four years, starting as a private and completing his service in 1946 as a captain. He fought in the European theater with the Seventy-first Infantry Division. In 1946, he was elected to the state Senate.

Jones was the legislature’s most compelling orator and also its most partisan, craftiest, and—some said—most vengeful member. The Arkansas Gazette called him “the noisiest, newsiest, most ferocious, entertaining and controversial man in the legislature.” In the Senate, Jones would exhibit many idiosyncrasies, such as relaxing with his red cowboy boots propped on his desk. Each day, he bought a dozen red boutonnieres and ceremoniously pinned them on people he decided to favor: senators, Senate employees, the chaplain, or reporters. At adjournment, he sometimes whipped a harmonica from his desk and played “Dixie.”

While he was feared and often resented in Faulkner County for his political intrigues, Jones changed the skyline and landscape of the community. His conniving and connections brought huge state investments to the county and elsewhere in his district.

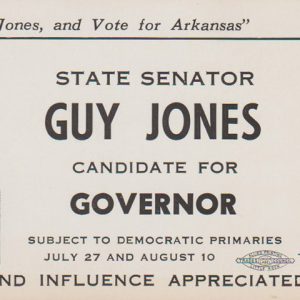

His clout grew after he ran for governor in 1954. Jones finished third in the preferential primary behind Governor Francis Cherry, who received forty-eight percent of the votes, and Orval Faubus. Faubus wanted Jones to endorse him in the runoff, which Jones agreed to do only if Faubus would pay for him to make six television talks around the state. Faubus agreed and, with Jones’s endorsement, won the election. For the next twelve years, Faubus obliged Jones’s whims, which consisted of placing many government facilities in Faulkner County, where they operated under Jones’s monitoring. These facilities included a state institution for the mentally disabled (now the Conway Human Development Center), the headquarters of the State Civil Defense Agency (now the Arkansas Department of Emergency Management), and the studios of Arkansas Educational Television Network (AETN). The state also built a park at Woolly Hollow sixteen miles north of Conway.

One product of Jones’s craftiness was the construction of a bridge across the Arkansas River at Toad Suck, linking Perry County and Conway. The state highway director had refused to buy a privately operated ferry at Toad Suck. At the end of the legislative session in March 1957, Jones checked out the Arkansas Department of Transportation’s appropriation bill for the next two years and took it home. The legislature adjourned without appropriating any money for the agency. The highway director relented, and Faubus called a special session to enact a highway appropriation. Jones amended the bill in the Senate to set aside $25,000 to buy the ferry. The federal Bureau of Public Roads (now the Federal Highway Administration) then built a bridge on the lock and dam at Toad Suck to relieve the state of operating the outmoded ferry.

When Winthrop Rockefeller, the first Republican governor of Arkansas since Reconstruction, was elected in 1966, he inherited a ferocious enemy in Jones, who fought him at every turn. The feud became personal for both men.

In 1972, Jones was indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of income-tax evasion. His first trial ended in a mistrial because someone had tampered with the jury, but he was convicted in 1973. He was fined $5,000, but the presiding judge remarked that he suspected that Jones’s prosecution had been politically motivated.

Jones’s colleagues in the Senate at first refused to expel him, but after a public outcry, the Senate reassembled on August 1, 1974, and voted twenty-five to six to remove him. The Arkansas Supreme Court revoked his license to practice law for a year, but, by 1982, he had regained the right to practice in both Arkansas and federal courts.

Jones died on August 10, 1986, and is buried at Oak Grove Cemetery in Conway.

For additional information:

Guy Hamilton Jones Papers. University of Central Arkansas Archives and Special Collections, Conway, Arkansas.

“Ex-Senator Dies at 75; Noted Orator.” Arkansas Gazette. August 12, 1986, pp. 1A, 5A.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Democratic Party

Democratic Party Jones Campaign Card

Jones Campaign Card  "Mutt" Jones Flyer

"Mutt" Jones Flyer

I would loved to have met him.