calsfoundation@cals.org

Fayetteville (Washington County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36º03’45″N 094º09’26″W |

| Elevation: | 1,400 feet |

| Area: | 54.14 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 93,949 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | August 23, 1870 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

425 |

598 |

972 |

955 |

1,788 |

2,942 |

4,061 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

4,471 |

5,362 |

7,394 |

8,212 |

17,071 |

20,274 |

30,729 |

36,608 |

42,099 |

58,047 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

73,580 |

93,949 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fayetteville, one of the largest cities in the state, is located in the Ozark Mountains and has been the seat of county government since formation by the state legislature. From the early pioneers to modern-day residents, Fayetteville’s citizens have been dedicated to the enhancement of the cultural, educational, and economic growth of the area and state.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The first settlers in Fayetteville were George McGarrah and his sons James, John, and William. Around 1828, they settled near the spring in an area that was to become the Masonic Addition to Fayetteville, the eastern part of which is at the base of Mount Sequoyah. James Leeper, a Revolutionary War veteran, was the second settler in Fayetteville. His son Matthew was appointed receiver of the Land Office by President Andrew Jackson. The Leepers owned all the land on the south side of Mount Sequoyah to the White River, as well as lots around the Fayetteville square. Matthew was married to Lucy Washington, and David Walker was married to her sister Jane Lewis Washington, representing the linking of two politically influential families in Fayetteville.

Washington County was established in 1828 out of Lovely County, which had existed for a year. The town of Washington Courthouse was the county seat, but the name was changed to Fayetteville in 1829 when a post office was established. Postmaster General William T. Barry ordered the change because of confusion with the name of Washington (Hempstead County). Two commissioners locating the county seat came from Fayetteville, Tennessee, and urged Barry to name it after that community.

On February 27, 1835, President Jackson issued a patent for 160 acres forming the original settlement. Upon a petition by more than two-thirds of the taxpayers, the county court granted their incorporation request in 1841. In 1859, the legislature granted a city charter.

Archibald Yell of Tennessee was named judge of the Superior Court of Arkansas Territory in 1835. He built a home, an office, and a guesthouse in Fayetteville on an estate he named Waxhaw in honor of Jackson’s South Carolina birthplace. Only his office remains, and it was moved in 1992 to the Washington County Historical Society grounds. It is one of the oldest structures in the state.

When Arkansas became a state in 1836, Yell was elected the first U.S. representative. He was the second governor, serving from 1840 to 1844. He served again in the House, until July 1, 1846, when he resigned to fight in the Mexican War. Fayetteville and Washington County sent more than 100 volunteers to fight in the war, many serving in Yell’s regiment.

The first newspaper, The Fayetteville Witness, was published in 1840 by C. F. Towns.

In the years leading to the Civil War, Fayetteville and the county gained a reputation as the state’s cultural and educational center. The Fayetteville Female Academy, founded under the guidance of Robert Mecklin, was incorporated on October 26, 1836, and was the second school chartered by the state. Sophia Sawyer established the Fayetteville Female Seminary and began teaching on July 1, 1839, with fourteen Cherokee girls as pupils. The next year, she had fifty-one pupils. Robert Graham started an academy in 1850, chartered as Arkansas College of Fayetteville on December 14, 1852. The first bachelor’s degrees in the state were granted by the college, and the college was given the power to confer doctoral degrees. On December 16, 1858, the state chartered the Fayetteville Female Institute, headed by T. B. Van Horne. “Fayetteville Polka,” the first piece of sheet music published by an Arkansan, was written by Austrian immigrant Ferdinand Zellner in 1856.

On July 7, 1856, two enslaved men, who had been tried an acquitted for the murder of enslaver James Boone, were lynched by a local mob. A marker commemorating this event was installed in Oaks Cemetery in 2021.

Civil War through Reconstruction

With the advent of the Civil War, Washington County elected four men with Unionist sympathies to represent them at the Arkansas Secession Convention; three were from Fayetteville. The convention met on March 5, 1861, selecting Judge David Walker of Fayetteville as chairman. After debates, members voted on March 16 against secession, 39–35.

After the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Walker issued a call on April 27, 1861, to reconvene the convention on May 6. At this meeting, the vote was 65–5 to secede. Walker called on the five dissenters to change their votes to make it unanimous. All did except Isaac Murphy of Madison County, formerly a Fayetteville teacher.

Fayetteville was little affected by military activity until February 1862, when Confederate troops moving south destroyed their arsenal in the Van Horne school building, burning and looting much of the town rather than letting any materials fall into the hands of Union forces.

During the war, the town was alternately possessed by both sides. There was a skirmish between Fayetteville and Cane Hill (Washington County) in November 1862. A skirmish at Fayetteville in August 1863 was followed by an affair at McGuire’s in October of the same year. There was an affair at Fayetteville in June 1864, and operations around Fayetteville later that same year. The Action at Fayetteville on April 18, 1863, was the only major conflict. Union Colonel Marcus LaRue Harrison made his headquarters in what had been Judge Jonas Tebbetts’s home at College and Dickson streets. Confederate General William L. Cabell tried to retake the town, with the battle centering on the Tebbetts home. The effort failed. The battle-scarred house, known today as the Headquarters House, still stands as a museum and the headquarters of the Washington County Historical Society.

During the Civil War, there was no local government except that of the military. Military farm colonies were established in an effort to help refugees become self-sufficient. In 1868, local government was reestablished under the legislative charter of 1859, and Harrison was elected mayor. Due to dissatisfaction with his administration, the citizens petitioned the legislature for dissolution of the 1859 charter, which was granted. On August 24, 1870, an order by the county court was placed in the record establishing the local government under a general statute.

Economic recovery began with the rebuilding of a town in complete ruin except for a few residences. Banking in the state was illegal from 1846 to 1868 due to the disastrous failure of the privately owned Real Estate Bank and the state-owned Arkansas State Bank. The Stark Bank opened in Fayetteville in November 1872, becoming the William McIlroy Bank on January 2, 1876; now Arvest Bank, it is the state’s oldest bank.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The Morrill Act, passed by Congress during the war, provided land grants to each state to establish agricultural and mechanical colleges. Upon reentering the Union, Arkansas became eligible for the grants. Washington County proposed a $100,000 bond issue, and Fayetteville offered another $30,000, including individual land donations, to build a college. Fayetteville’s proposal was selected, and Arkansas Industrial University opened on January 22, 1872. In 1899, the legislature changed the name to the University of Arkansas (UA).

Transportation continued to be by wagon, stagecoach, horse, and buggy for the rest of the nineteenth century, except for rail service furnished primarily by the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway Co. (SLSF), built over a period of fourteen years. The Pacific & Great Eastern Railroad Co., incorporated on October 23, 1884, built a line to Wyman twelve miles east of Fayetteville. The line was doomed when the SLSF built a branch line to St. Paul and Pettigrew in Madison County. The St. Paul branch provided a great amount of hardwood for processing into railroad ties, furniture, handles, and various other wood products. About 1900, construction started on a railroad to the west, known as the Ozark & Cherokee Central Railway. It was first completed to Westville, Oklahoma, and later extended to Tahlequah and Muskogee, Oklahoma. The line was later purchased by the SLSF. For many years, the railroads were a major boost to the economic growth of Fayetteville, providing a faster and more efficient method of moving commodities in and out of the area, as well as passenger service to distant destinations.

The town’s economy after the war centered on timber, apples, tomatoes, and other fruits and vegetables that were processed, packed, and shipped out. Production of wood products and of bricks made from native clay met the growing need for construction of houses and public buildings.

Early Twentieth Century

At the beginning of the Spanish-American War in 1898, favorite sons and university students volunteered for service. The Mexican border conflict followed, and on June 16, 1916, Company B, Arkansas National Guard, received orders to mobilize. The unit returned on March 15, 1917, less than a month before the United States declared war on Germany (April 6, 1917) and entered World War I.

Registration for the draft began June 5, 1917. Company B, which later became Battery B, 142nd Field Artillery, received orders to mobilize on August 5, 1917. On June 15, 1918, the UA grounds became a training camp starting with 153 men and growing to 300. Citizens who stayed behind became involved in the war effort by working with benevolent organizations and pooling their resources as part of the United War Work Fund.

In the early twentieth century, attempts were made to move the university or parts of it to a more central location in Arkansas. The primary argument was the distance for students in other areas of the state. Attempts made in the legislative sessions of 1909, 1915, and 1921 all failed.

Advances in communication and transportation eased the remoteness of Fayetteville. The first telegraph wire came through Fayetteville in 1860, strung from Jefferson City, Missouri, to Fort Smith (Sebastian County). In 1886, E. C. Boudinot and W. C. Davenport formed the Washington County Telephone Company, starting the first telephone exchange. When wireless telegraphing became a reality, UA erected a 125-foot wooden tower for sending coded messages. Students of electricity used the telegraph from 1900 to 1905. In 1924, the university erected a wireless apparatus and began broadcasting as KFMQ radio, later changed to KUOA; it is recognized as one of the oldest radio stations in the world. UA sold KUOA to a commercial company in 1933 who in turn sold it to John Brown University in Siloam Springs (Benton County).

Glenn L. Martin piloted the first airplane flight in the county on September 1, 1911, at the county fair on the site that became the University Indoor Tennis Facility. The automobile first met with ridicule and was sometimes referred to as the “Devil’s machine,” though it later proved to be an economic boon. Railroads began to lose business as trucking expanded and served points not near a railroad. Fayetteville’s first efforts to apply hard surfaces to streets began in 1917. In the next ten years, twenty-five miles were paved at a cost of $500,000. Trucks first made short deliveries and pickups only in dry weather. In time, regularly scheduled truck lines went to Huntsville (Madison County), Springdale (Washington and Benton counties), and Winslow (Washington County).

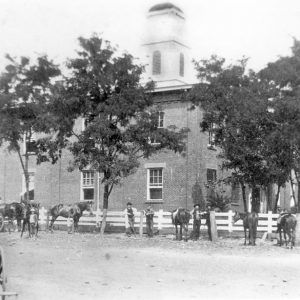

The historic Washington County Courthouse, erected in 1904, still stands and continues to be used by the county in an auxiliary capacity.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Airplanes used small landing strips until 1929, when land was purchased for $5,000 to build the first permanent airport. From 1942 to 1944, the field was used to train pilots and instructors for World War II. Programs were operated in conjunction with UA. More than 2,400 students in the 305th College Training Detachment received pilot training from March 1, 1943, to June 30, 1944.

Dramatic growth in production beginning in the 1930s would make poultry the main agriculture product by the 1950s. With the exception of grapes, production of most other agriculture products declined or showed little increase. This led to a change from canning to other forms of processing.

In 1947, George Lee Lenox opened what would become the Rockwood Club, which became, in the 1950s, a premier regional venue for musical acts, including a number of national figures, such as Jerry Lee Lewis and Roy Orbison. As the university population grew in the postwar years, Fayetteville became an important cultural center. In 1954, Fayetteville became one of the first cities in the South to desegregate its school system.

Modern Era

In 1970, Fayetteville began developing an industrial park to centralize and diversify industries. The Women’s Library, a volunteer operation, was open from 1982 until 2000. In the twenty-first century, Fayetteville has nine elementary schools, two middle schools, two junior high schools, and one high school. The public school system operates the Technical Center, Adult and Community Education Center, Environmental Center, Migrant Program Center, and Youth Apprenticeship program. In 1990, the current Washington County Courthouse was built.

Among products made or processed in the area are poultry, dairy, electrical equipment, hand tools, automotive equipment, and printed business forms. Fayetteville is a center for banking and finance, real estate, insurance, building industry, and retail and wholesale trades.

On August 19, 2014, the Fayetteville City Council approved a civil rights ordinance that protects people in Fayetteville from discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation. However, voters overturned the ordinance on December 9, 2014. A new ordinance, one with greater exceptions for religious institutions, went before the voters on September 8, 2015, and passed.

Attractions

Among the local attractions are UA and its Razorback athletic events, the Walton Arts Center, Arkansas Air Museum, Ozark Military Museum, and Fayetteville Public Library. Among local sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places are the Walker-Stone House, Tebbetts House, Joe Marsh and Maxine Clark House, John G. Williams House No. 2, Washington-Willow Street Historical District, the Clinton House Museum, and Mount Sequoyah Cottages. The E. Fay Jones House and the Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge House are both available to view, as is the Botanical Garden of the Ozarks. The OMNI Center for Peace, Justice and Ecology is based in Fayetteville, and Washington Regional Medical Center in Fayetteville serves the area. There are many historic cemeteries in the city, including the Fayetteville National Cemetery, Fayetteville Confederate Cemetery, and Evergreen Cemetery. In addition, Fayetteville is one of two locations in the state to feature a Strengthen the Arm of Liberty monument.

Notable Figures

John Ridge was a Cherokee leader who hoped that a move west might keep the Cherokee people from being wiped out by white soldiers. After he was assassinated for his part in negotiating the loss of Cherokee lands in the East, his widow, Sarah Ridge, took herself, her children, and their teacher Sophia Sawyer to Fayetteville. Both Ridge and Sawyer were instrumental in establishing the town’s reputation as a center for education.

Fayetteville has produced many people of national and world fame, including the noted black poet George Ballard, poet and folklorist Irene Carlisle, Governor Charles Hillman Brough, opera singer Mabel Patricia Chapman and opera producer/director Sarah Caldwell, Congressman Hugh Anderson Dinsmore, Senator J. William Fulbright, Senator Carl R. Gray, and architects E. Fay Jones and Edward Durell Stone.

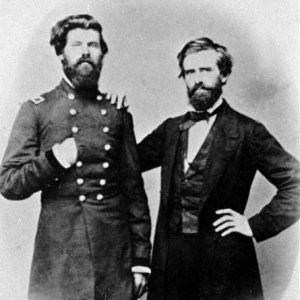

Samuel Pinckney Pittman, a Confederate Civil War soldier, was born and grew up on a family farm southwest of Fayetteville. Carlos Ludwig von Berg, a Union Civil War soldier, settled in the Fayetteville area later in life.

Other local figures include professors Henry McMillan Alexander and Walter John Lemke; biographer Jack Appleby; astronomer and mathematician Herbert Earle Buchanan; musicians Twila Paris and the Cate Brothers; decorator Paul Martin Heerwagen; authors Joan Edmiston Hess, Kay Goss, and Charles Morrow Wilson; activist Lessie Stringfellow Read, and church leader and writer Grace Adkins.

For additional information:

Alison, Charles Y. A Brief History of Fayetteville, Arkansas. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2017.

Benson, Willie. “Gentrification and Income Segregation in Fayetteville, Arkansas.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020.

Brown, Kent R. Fayetteville, A Pictorial History. Norfolk, VA: Donning Co., 1982.

Campbell, Denele. Good Times: A History of Night Spots and Live Music in Fayetteville, Arkansas. N.p.: 2020.

Campbell, William Simeon. One Hundred Years of Fayetteville 1828–1928. Fayetteville: Washington County Historical Society, 1977.

City of Fayetteville, Arkansas. http://www.fayetteville-ar.gov/ (accessed July 19, 2023).

Eifling, Stephanie. “The Rise and Fall of Schuler Town.” Arkansas Times, September 1986, pp. 48–51, 66, 68–69.

Fayetteville History. http://www.fayettevillehistory.com/ (accessed July 19, 2023).

Hickey, Jordan P. “‘Can’t Have It Both Ways’: As Northwest Arkansas Booms, Residents Are Asking: Does Fayetteville Still Belong to Them?” Arkansas Times, April 2025, pp. 48–54. Online at https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2025/04/07/as-northwest-arkansas-booms-residents-are-asking-does-fayetteville-still-belong-to-them (accessed April 7, 2025).

Hogan, J. B. Forgotten Fayetteville and Washington County. Springfield, MO: Roan & Weatherford Publishing Associates, 2023.

Mahan, Russell L. Fayetteville, Arkansas, in the Civil War, 1860–1865. Bountiful, UT: Historical Byways, 2003.

Wappel, Anthony J., and Ethel Simpson. Once Upon Dickson Street: An Illustrated History, 1868–2000. Fayetteville, AR: Phoenix International, 2008.

Wappel, Anthony J., and J. B. Hogan. The Square Book: An Illustrated History of the Fayetteville Square, 1828–2016. N.p.: 2017.

Charles W. Stewart

Washington County Historical Society

Arkansas Air Museum

Arkansas Air Museum  Fayetteville Aerial View

Fayetteville Aerial View  Fayetteville Angels

Fayetteville Angels  Fayetteville Confederate Cemetery

Fayetteville Confederate Cemetery  Fayetteville Federal Courthouse

Fayetteville Federal Courthouse  Fayetteville Female Seminary

Fayetteville Female Seminary  Fayetteville Frisco Depot

Fayetteville Frisco Depot  Fayettevile Opera House

Fayettevile Opera House  "Fayetteville Polka"

"Fayetteville Polka"  Fayetteville Street Scene

Fayetteville Street Scene  Fayetteville Vulcanizing Company

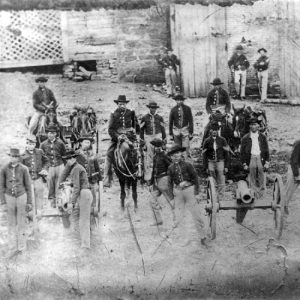

Fayetteville Vulcanizing Company  First Arkansas Light Artillery Battery

First Arkansas Light Artillery Battery  Fulbright Building

Fulbright Building  Futrall House

Futrall House  Lafayette Gregg Home

Lafayette Gregg Home  Headquarters House Museum

Headquarters House Museum  Headquarters House Museum

Headquarters House Museum  Headquarters House Museum

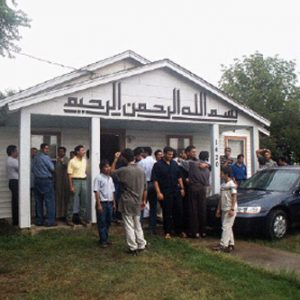

Headquarters House Museum  Islamic Center of Northwest Arkansas

Islamic Center of Northwest Arkansas  Maple Street Bridge

Maple Street Bridge  Mount Sequoyah Cottages

Mount Sequoyah Cottages  Old Main Building, UA

Old Main Building, UA  Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge House

Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge House  Jonas Tebbetts

Jonas Tebbetts  University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville  University of Arkansas's First Buildings

University of Arkansas's First Buildings  Walton Arts Center

Walton Arts Center  Walton Arts Center

Walton Arts Center  Walton Arts Center Groundbreaking

Walton Arts Center Groundbreaking  Washington County Courthouse

Washington County Courthouse  Old Washington County Courthouse

Old Washington County Courthouse  Washington County Map

Washington County Map  Archibald Yell Law Office

Archibald Yell Law Office  Zerbe Air Sedan

Zerbe Air Sedan

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.