calsfoundation@cals.org

Ed Ware (1882–1929)

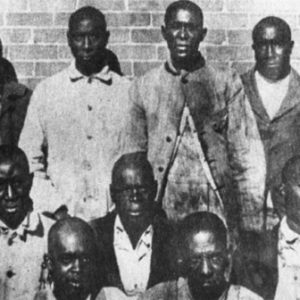

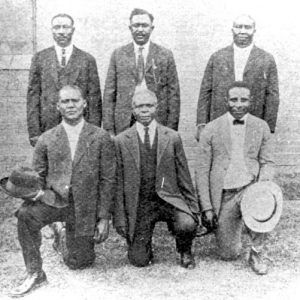

Ed Ware was one of twelve African-American men accused of murder following the Elaine Massacre of 1919. After brief trials, the so-called Elaine Twelve—six who became known as the Moore defendants and six who became known as the Ware defendants (so called using Ed Ware’s name)—were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Ultimately, the Ware defendants were freed by the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1923; after numerous legal efforts, the Moore defendants were released in 1925.

Ed Ware was born in Mississippi on March 7, 1882, to William Ware and Ann Ware. He moved to Arkansas City (Desha County) around 1910. Ed Ware was employed as a farmhand in the region. On September 12, 1918, he registered for the draft into the U.S. military. By this time, he and his wife, Lula Ware (who he had married around 1910), had migrated to Jones County, Mississippi, and both were working as sharecroppers. Nothing is known of his military service during World War I or when he was discharged.

Ed and Lula relocated to Elaine (Phillips County) sometime prior to 1919. Ware prospered in growing cotton, owning 120 acres, and became the secretary of the Hoop Spur (Phillips County) lodge chapter of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA). Three days before the violence in Elaine started, Ware riled white landowners in Elaine by refusing to sell two bales of cotton at lower-than-average prices. Ware was subsequently refused settlement of his account at the local mercantile store and went to Helena (Phillips County) to seek legal advice in the matter. Rumors spread that the whites would lynch him for his obstinacy.

A 1916 federal study of plantation conditions in Arkansas warned that there was acute unrest due to the tenant farming system and oppressive landlords, and that this could lead to organized resistance. The PFHUA held a meeting on September 30, 1919, with black sharecroppers gathering at a church in the town of Hoop Spur, three miles north of Elaine. The purpose of the meeting was to seek more money for their crops from the landowners. Two black men, Alfred Banks and John Martin, were positioned as guards for this meeting. An exchange of gunfire erupted, and W. A. Adkins, employed as a security officer for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, was killed, and Charles Pratt, a Phillips County deputy sheriff, was wounded; both were white. The shooting escalated into mob violence against the area’s black citizens, and although the exact number is unknown, estimates of the number of African Americans killed by whites range into the hundreds; five white people died.

Ware and his wife were present that night, and he recounted in his later testimony before the court, “On the 30th of September 1919, we met in a regular meeting and while sitting attending to our business about 11 o’clock that night, some automobiles were heard to stop north of the church and in just a few minutes they began shooting in the church and did kill some people in the church…” The next morning, 150 armed white men arrived at Ware’s house and threatened to kill him and all of the other members of the union. He left his home and waited in a field about 200 yards away with Isaac Bird and Charley Robinson, a fellow member of the PFHUA. The mob surrounded his house and shot at the three men when they attempted to flee the area. Robinson was killed by the white mob, who then placed him in Lula Ware’s bed. She had been arrested shortly before by white authorities and was released after four weeks of hard labor. All of the Wares’ property, livestock, and household goods were stolen.

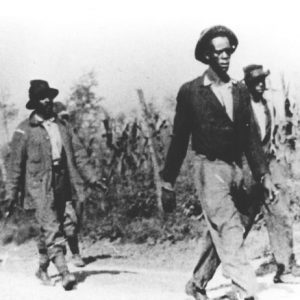

To avoid being captured or lynched by the mob, Ware and his friend Will McFarland trekked about forty miles to the town of Brickeys (Lee County). From this location, they took a train for Memphis, Tennessee, before making their way to New Orleans, Louisiana. Ware began working under the assumed name Charles Harper as a wagon driver for an ice cream company, while McFarland found employment as an “exhorter” on the streets of New Orleans. They managed to hide out in the city for ten days before being arrested on November 9, 1919, by local authorities and extradited to Arkansas.

Ed Ware was among the twelve black sharecroppers who would be charged with murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair in the aftermath of the violence. Ware was identified as one of the union’s leaders who were accused of conspiring to kill whites during the Elaine Massacre. These claims were likely due to his leadership role in the union and his relative prosperity, which made him a target of white landowners in the region. Denying all involvement, Ware testified that he had only joined the union because he was promised 160 acres of land if he paid a $10 fee to the organization. Further, he was not in possession of a weapon when he was at the church during the time of the shooting.

Their cases drew the attention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and civil rights lawyer Scipio A. Jones came to the defense of Ware and the other eleven defendants who had been sentenced to death. In December 1919, the men were granted a stay of execution by Governor Charles Brough, allowing for appeal. In March 1920, his death sentence, along with those of the five other Ware defendants (Alfred Banks, William Wordlaw, Albert Giles, Joe Fox, and John Martin), was reversed by the Arkansas Supreme Court, and they were sent back to Helena for a new trial based on a technicality. A May 1920 retrial in Helena upheld the convictions. In December 1920, the Arkansas Supreme Court reversed the decision from Helena and called for a new trial. An April 1923 petition demanded the release of the prisoners due to the lack of trials for the last two court sessions, and on appeal, the Arkansas Supreme Court agreed, releasing Ware and the five others. The other six members of the Elaine Twelve, the Moore defendants, were released in 1925.

Little is known of Ed Ware’s life after he was granted his freedom. He relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, with his wife and died there on February 3, 1929. Lula Ware died on February 23, 1954, and is buried next to her husband at the Father Dickson Cemetery in St. Louis.

For additional information:

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Lancaster, Guy, ed. The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Wells, Ida B. “The Arkansas Race Riot.” Chicago: 1920. https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot (accessed May 9, 2019).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown, 2008.

Brian K. Mitchell, Alex Soulard, Kathryn Thompson

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.