calsfoundation@cals.org

Alfred Banks (1895?–1944)

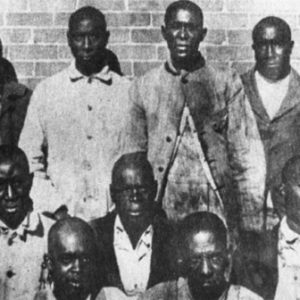

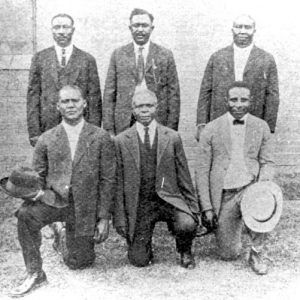

Alfred (Alf) Banks was one of twelve African-American men accused of murder following the Elaine Massacre of 1919. After brief trials, the so-called Elaine Twelve—six who became known as the Moore defendants and six (including Banks) who became known as the Ware defendants—were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Ultimately, the Ware defendants were freed by the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1923; after numerous legal efforts, the Moore defendants were released in 1925.

There are conflicting dates as to when Alfred Banks Jr. was born. The 1930 census indicates 1895, his World War I draft registration card shows 1897, and his Missouri death certificate gives 1899. Whatever the year, Banks was born on either August 23 or 24 in Lake Providence, East Carroll Parish, Louisiana, to Alfred Banks Sr. and Angeline Walton (Maggie) Banks. In 1910, he lived in East Carroll Parish’s Police Jury Ward 3 with three siblings—Carrie, Annie, and Florence Christuras. In 1917, Banks was working in Arkansas in the farming industry for the Howe Lumber Company in Wabash (Phillips County), as noted on his World War I draft registration card. Banks received an exemption, possibly because he was a farmer.

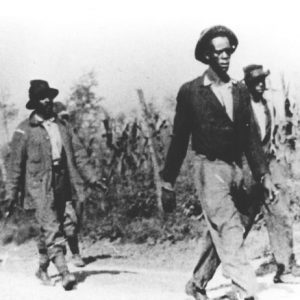

A 1916 federal study of plantation conditions in Arkansas warned that there was acute unrest due to the tenant farming system and oppressive landlords, and that this could lead to organized resistance. The Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America held a meeting on September 30, 1919, with black sharecroppers gathering at a church in the town of Hoop Spur (Phillips County), three miles north of Elaine (Phillips County). The purpose of the meeting was to seek more money for their crops from the landowners. Banks and John Martin were positioned as guards for this meeting. An exchange of gunfire erupted, and W. A. Adkins, employed as a security officer for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, was killed, and Charles Pratt, a Phillips County deputy sheriff, was wounded; both were white. The shooting escalated into mob violence against the area’s black citizens, and although the exact number is unknown, estimates of the number of African Americans killed by whites range into the hundreds; five white people died.

Before the meeting and ensuing riots, Banks had worked a combined forty acres of cotton and corn, with one acre of “truck patch” (a plot of land to grow food to sell). According to Ida B. Wells in The Arkansas Race Riot, Banks had harvested thirty-two bales of cotton with an estimated valued of $7,200. After the riots, he lost everything.

Starting on October 27 and concluding on October 31, 1919, a total of 122 African Americans were arrested and charged with crimes ranging from murder to “nightriding.” On November 4, Banks and Martin were convicted and sentenced to death in less than nine minutes on the charge of first-degree murder of Adkins. After his trial, according to later affidavits, he was tortured and forced to testify against Joe Fox, Albert Giles, and William Wordlaw (sometimes spelled Wardlow or Wordlow).

Their cases drew the attention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and civil rights lawyer Scipio A. Jones came to the defense of Banks and the other eleven defendants who had been sentenced to death. Soon after his conviction, Banks was transferred to Little Rock (Pulaski County), arriving on November 22, 1919. In December 1919, the men were granted a stay of execution by Governor Charles Brough, allowing for appeal. In March 1920, his death sentence, along with those of the five other Ware defendants (Ed Ware, William Wordlaw, Albert Giles, Joe Fox, and John Martin), was reversed by the Arkansas Supreme Court, and they were sent back to Helena (Phillips County) for a new trial based on a technicality. A May 1920 retrial in Helena upheld the convictions. In December 1920, the Arkansas Supreme Court reversed the decision from Helena and called for a new trial. An April 1923 petition demanded the release of the prisoners due to the lack of trials for the last two court sessions, and on appeal, the Arkansas Supreme Court agreed, releasing Banks and the five others. The other six members of the Elaine Twelve, the Moore defendants, were released in 1925.

After his release from prison in June 1923, Banks moved to St. Louis, Missouri. He married Sarilda Woods in 1924. The 1930 census recorded that Banks made a living in St. Louis as a janitor.

Banks died on March 30, 1941, of lung cancer. He had been employed by Scullins Steel company as a laborer at the time of his death. He is buried at Booker T. Washington Cemetery in Centreville, Illinois. Sarilda, his wife, died on April 23, 1944, of complications related to diabetes.

For additional information:

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Lancaster, Guy, ed. The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. “The Arkansas Race Riot.” Online at https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot (accessed January 4, 2019).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown, 2008.

Brian K. Mitchell, Jessica Chavez, Kary Goetz

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.