calsfoundation@cals.org

North Little Rock (Pulaski County)

aka: Argenta (Pulaski County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º46’10″N 092º16’01″W |

| Elevation: | 280 feet |

| Area: | 52.33 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 64,591 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | July 17, 1901 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

11,138 |

14,048 |

19,418 |

21,137 |

44,097 |

58,032 |

60,040 |

64,388 |

61,741 |

60,433 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|||||

|

62,304 |

64,591 |

|

|

|

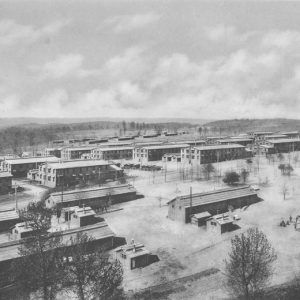

North Little Rock is the state’s sixth-largest city (as of 2010), though once the second largest, with historical ties to the transportation industry and the military. Before railroad companies spurred the growth of a town of mills, stockyards, and small businesses in the last three decades of the nineteenth century, the flood-prone north side of the Arkansas River across from Little Rock (Pulaski County) had few residents. But starting in the 1820s, its ferry and riverboat terminals prospered at a junction of roads on routes between St. Louis, Missouri, or Memphis, Tennessee, and Texas or Oklahoma. The military continues to have an economically viable relationship with central Arkansas, with Fort Logan H. Roots atop Big Rock Mountain since 1897; Camp Pike, established northwest of the city in 1917; Camp Robinson, headquarters of the Arkansas National Guard; and the nearby Little Rock Air Force Base in Jacksonville (Pulaski County). In 1921, the U.S. Congress established Fort Roots as a veterans hospital, which is known today as the Eugene J. Towbin Healthcare Center.

Early Statehood through the Gilded Age

Chronic flooding on the low north bank, while good for farming, killed early efforts to found any large settlement in the nineteenth century. One venture that led to financial ruin, the town of DeCantillon, washed away in the flood of 1840. The northside junction was a major crossroads and campground for the relocation on the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma of 50,000 Native Americans in the 1830s and 1840s. During the Civil War, an unincorporated town known as Huntersville clustered around the Memphis and Little Rock Railway depot near the north approach to what is today the Junction Bridge.

Vestal Nursery, started in 1860, was operational for over a hundred years.

In 1865, William E. Woodruff, founder of the Arkansas Gazette, tried to sell lots on the platted town site of Quapaw immediately east of Huntersville, yet nothing more was heard of it beyond newspaper ads. The heirs of territorial and early statehood politician Thomas W. Newton Sr. platted the town of Argenta in 1866. The name, derived from the Latin “argentum” (silver), recognized Newton’s leadership during the late 1840s and early 1850s in the Southwest Arkansas Mining Company that operated the Kellogg lead and silver mine about ten miles north of Argenta. A majority of the population on the north side in 1870 was African American, including many former slaves. European immigrants began arriving in the 1870s to take the railroad jobs and other employment connected to the railroads, fueling development of Argenta. Mining at Big Rock quarry, as well as timber and agriculture, also benefited from the access to transportation. Argenta likely gained the unwanted nickname of “Dogtown” from this working-class origin. According to oral tradition, people from Little Rock dumped their unwanted dogs in North Little Rock, but the name probably predates this practice and was a disparagement of the north side’s blue-collar base. In the mid-1900s, Little Rock students often taunted North Little Rock students with chants of “Dogtown” at sporting and other events.

The Baring Cross Bridge (named after British financial backers Baring Brothers of London) opened for railroad, wagon, and foot traffic in 1873, becoming the first permanent structure across the Arkansas River. It was followed by the Valley Route (Junction) Bridge in 1884, the free bridge in 1897, and the Rock Island Bridge in 1899. But, politically, the territory remained unincorporated until Little Rock forcibly annexed it in 1890 without giving northsiders a vote in the matter.

The town of North Little Rock was organized on July 1, 1901, as part of an elaborate scheme hatched by politician and businessman William C. Faucette to reclaim Argenta, which Little Rock called the Eighth Ward. The secret plan to reannex Argenta grew out of resentment by north side residents who never wanted to be a part of Little Rock. Faucette, an Eighth Ward representative on the Little Rock City Council, frequently complained of the lack of services provided to Argenta during the 1890s and early 1900s, despite the payment of taxes to the south-side city. North Little Rock’s southern boundary from 1901 to 1904 bordered the Eighth Ward along what is today Fifteenth Street. Legislation known as the Hoxie-Walnut Ridge bill was signed into law in 1903 and surprised Little Rock’s leaders as to its statewide implications—because any town or city within a mile of another had the ability to annex all or part of the other. Sponsors of the bill worked secretly with Faucette and other northside businessmen to disguise the bill’s true intent, which also provided that only electors in the areas to be merged could vote on annexation. Little Rock sued to try to stop the election. The courts allowed it to proceed on July 21, 1903, although the state Supreme Court sealed the results, which overwhelmingly favored annexation. The state Supreme Court upheld “Hoxie-Walnut Ridge” on February 6, 1904, and North Little Rock, a rural town of about 1,200, officially took control of the Eighth Ward on February 23. Three days later, North Little Rock, by proclamation of the governor, became a first-class city with a population of 8,203.

Early Twentieth Century

Faucette was elected the first mayor of the new city government on April 5, 1904. All three previous mayors of the old town of North Little Rock—Frank Cook, William Mara, and Michael Brown—guided the town and its five-member council from 1901 to 1904. The North Little Rock City Council, an eight-member board, first met on April 11, 1904, in the fire station at 506 Newton Avenue (now Main Street). In January 1906, the city adopted Argenta as its name but changed it back to North Little Rock in October 1917 at the urging of James P. Faucette, the first mayor’s brother and the city’s third mayor. The elder Faucette died in January 1914, after which the town built a new city hall and opened it in 1915 in his honor. The building at Main and Broadway is still the city’s seat of government.

The Argenta Race Riot of 1906 saw the death of three African-American men and the burning of several businesses and homes. The violence, which spanned a few days in October 1906, had its origins in the separate deaths of two black men at the hands of two white men the previous month.

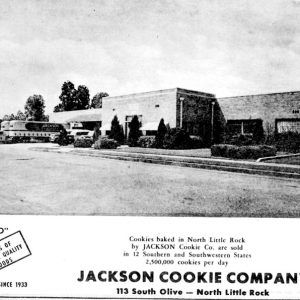

West of Argenta, the railroad and farming community of Baring Cross (named after the bridge) incorporated in 1896, but in January 1905, it voted to join North Little Rock. Similarly, the settlement of Levy northwest of Argenta incorporated in 1917 with a mayor and five aldermen and became a second-class city in 1941. Levy (named for Morris Levy, a prominent Argenta merchant) was annexed voluntarily by North Little Rock in 1946. The unincorporated areas of Rose City, Dixie, Park Hill, Fort Roots, and others were annexed in 1946, enabling North Little Rock’s population to leap from 21,137 in 1940 to 39,552 in a special census in 1948. Beginning in the 1890s, Rose City and later Dixie were home to manufacturers, cotton oil mills, and many blue collar workers. The Jackson Cookie Company, founded in 1933, continued production until 2022.

Park Hill, perched on ridges above the river valley, was the brainchild of Justin Matthews Sr., who also spurred the development of the Lakewood and Sylvan Hills neighborhoods. Construction in Park Hill began in 1922 and blossomed until the Depression. Despite the economic downturn, which led to the closing of numerous small businesses in the downtown, Matthews’s company completed the future Lakewood’s six lakes in 1932. He also commissioned Mexican sculptor Dionicio Rodriguez, who had perfected the faux bois (fake wood) technique, for construction of the Old Mill in Lakewood’s Pugh Memorial Park in 1933. The mill, a replica, is one of the city’s major attractions and appeared in the opening credits of the 1939 movie Gone with the Wind. However, the Depression brought the development of Park Hill to a near stand-still and delayed the development of Lakewood until the latter half of the 1940s.

World War II through the Modern Era

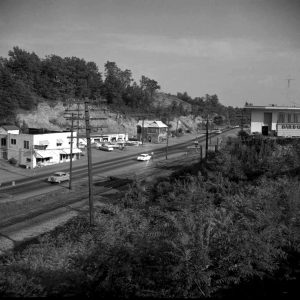

After World War II, building activity picked up again, and Lakewood came to fruition in the 1950s and 1960s. Other residential developments in that period were Glenview, Ranch Estates in Amboy, and Indian Hills. In 1949, the city acquired 870 acres—and another 700 acres in 1955—from the federal government for development of Burns Park, one of the nation’s largest municipal parks. It was named for physician and parks advocate William Burns, a former North Little Rock mayor. William F. “Casey” Laman, mayor from 1958 to 1972 and 1979 to 1980, spearheaded the construction of ball fields, tennis courts, pavilions, and other park amenities. In the early 1960s, Laman relocated the city’s police and courts headquarters and library (named for Laman) to Pershing Boulevard. Memorial Hospital also opened on the hill above Pike Plaza. During the Laman administration, the city started five recreation centers, built a new main fire station as well as two branches and improved its sewer system and electric company.

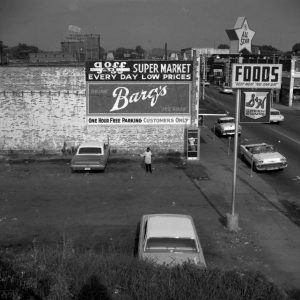

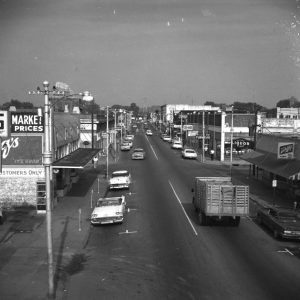

Urban renewal from 1960 to 1980 modernized the city’s poorest neighborhoods, but it also displaced many residents, slowed population growth, and razed most of the city’s historic downtown south of Broadway. McCain Mall, the state’s largest, opened in 1973 during a period of smaller mall openings in suburban areas. While suburban growth has continued, a downtown revitalization movement that began in the early 1990s has led to the restoration of historic properties and construction in older areas. The city’s oldest commercial building at 4th and Main has housed three pharmacies since its construction in 1887—Humphreys Drugs (1887–1903), Hall Drug Company (1903–1916), and Argenta Drug Company (1917–present). Alltel Arena opened near the river as a sports and entertainment venue in 1999; ten years later the name was changed to Verizon Arena due to a corporate merger, and it 2019 it was renamed yet again to Simmons Bank Arena. In 2005, the city, under the leadership of Mayor Patrick Hays, launched the Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum with the USS Razorback, a submarine commissioned in 1944, as its centerpiece. The submarine served in World War II and the Vietnam War under the U.S. flag and in the Cold War under the Turkish flag. Adjacent to the museum is the Beacon of Peace and Hope sculpture. In 2005, North Little Rock voters approved a two-year, one-percent sales tax for construction of the Dickey-Stephens baseball stadium on land adjacent to the Broadway Bridge. It became the new home of the Arkansas Travelers minor league baseball team.

North Little Rock was one of many Arkansas locations affected by the Flood of 2019. On March 31, 2023, the city was hit by a tornado that killed one person and damaged large portions of the city, including Burns Park, before to the northeast.

Education

A rural school district that dated to the 1870s was replaced by the North Little Rock School District in 1901, shortly after North Little Rock incorporated. Northside High School (through grade eleven) was built in 1902. Argenta High School, built in 1912, became a junior high in 1929 with the opening of the present Art Deco–style North Little Rock High School building designed by noted architect George R. Mann. Scipio A. Jones High School, an African-American school, started teaching through the twelfth grade in 1928. Named for a civil rights activist and lawyer born a slave, Jones High closed in 1970 during the desegregation of North Little Rock schools. The district opened a new high school, Northeast, in 1970 but merged the city’s two high schools in 1990.

Just days after the Little Rock Nine brought national attention to desegregation efforts in Little Rock, the North Little Rock Six faced similar circumstances outside North Little Rock High School. However, their attempts to desegregate that particular school proved unsuccessful.

North Little Rock public schools enroll more than 8,000 students, down from a peak of about 13,000 in the early 1970s. Immaculate Conception, Immaculate Heart of Mary, St. Patrick’s (the city’s oldest parochial school), and Central Arkansas Christian Schools offer private education. North Little Rock has a pair of two-year higher-learning institutions: Shorter College, which located in Argenta in 1897, and Pulaski Vocational Technical College (now University of Arkansas-Pulaski Technical College), which moved to the city in 1976.

Famous Residents

Among North Little Rock’s famous former residents are Jerry Jones, the Dallas Cowboys owner, and movie actresses Mary Steenburgen and Joey Lauren Adams. Al Bell, former owner of Stax Records, was part of the Memphis music scene, developing rhythm and blues legends such as Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Booker T. and the MGs. Samuel P. Massie Jr., whose parents taught school while he grew up in North Little Rock, was recognized as one of the top seventy-five chemists of the twentieth century.

Additional residents of note have included jockey Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton, writer and producer Paula Marie Martin, author and musician Mary Myrtle Medearis, stunt double Monica Staggs, educator Curtis Sykes, and biochemist Virginia Anne Rice Williams.

Attractions

Baker House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, the Justin Matthews Jr. House was listed in 1990, and the Argenta Historic District was listed in 1993. The Arkansas National Guard Museum is free and open to the public. North Little Rock is home to a municipal airport as well as one of two Arkansas State Veterans Cemeteries for the interment of military veterans and selected family members. Crystal Hill is a bluff consisting of sandstone, shale, and sparkling iron pyrite; it also shares the name with the nearby neighborhood. RiverFest, a music festival, was held on both sides of the river for many years on Memorial Day weekend.

For additional information:

Adams, Walter M. North Little Rock, the Unique City: A History. Little Rock: August House, 1986.

———. “The Railroads of North Little Rock.” Unpublished manuscript, 1980. North Little Rock History Commission, North Little Rock, Arkansas.

Bradburn, Cary. On the Opposite Shore: The Making of North Little Rock. Marceline, Mo: Walsworth Publishing Company, 2004.

City of North Little Rock. http://www.northlr.org/ (accessed April 12, 2023).

Drew, Sara Ann. “A History of Argenta.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock 2010.

Faucette Brothers Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://cdm15728.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/search/searchterm/mss.98.21 (accessed July 11, 2025).

Glover, Judy. “North Little Rock: A City in Crisis.” Arkansas Times, November 1979, pp. 58–60, 62–64, 66–67.

Johnson, Jajuan. “Dark Hollow: An African American Community in North Little Rock.” Pulaski County Historical Review 72 (Spring 2024): 1–12.

Littlefield, Daniel F., Amanda Page, and Fuller L. Bumpers. “The North Little Rock Site: Interpretive Contexts.” Trail of Tears study. Sequoyah Research Center. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Nieser, Tracy. “The History of Camp Pike, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 41 (Fall 1993): 64–71.

Nutt, Tim G. “Floods, Flatcars and Floozies: Creating the City of North Little Rock, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 41 (Summer 1993): 26–38.

Cary Bradburn

North Little Rock History Commission

Additional notable people include Wes Bentley and friend, Josh Cowdery–both actors and graduates of Sylvan Hills High School.

Argenta has changed into a very active place with new restaurants, the Joint Comedy Club, ACT, several breweries, the plaza, and much more. I am proud to live here.