calsfoundation@cals.org

Clarksville (Johnson County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º28’17″N 093º27’59″W |

| Elevation: | 379 feet |

| Area: | 18.53 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 9,381 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | December 21, 1848 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

466 |

656 |

937 |

1,086 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,456 |

2,127 |

3,031 |

3,118 |

4,343 |

3,919 |

4,616 |

5,237 |

5,833 |

7,719 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9,178 |

9,381 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clarksville is located on Spadra Creek, north of the Arkansas River. Although not on the banks of the river, and without the initial economic importance of the river communities, it grew steadily as the county seat. When stagecoach and train transportation became more common, land routes from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Fort Smith (Sebastian County) were directed through Clarksville, which evolved as an important stop. Development of important educational opportunities began with the organization of the town and continue to the present day. A broad mix of agriculture, mining, and manufacturing has supported the town’s growth.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

A Native American presence is evidenced by the “Rock House,” a red limestone cave in which many early drawings were found, and other sites. As early as 1820, an Indian factory, headed by Colonel Matthew Lyon, existed near Spadra. The Spadra area today hosts a state recreation area on the Arkansas River. The Cherokee moved into this area after the Osage tribe was relocated by treaty. Other tribes moved in around 1828, when treaties gave land in present-day Oklahoma to the Cherokee. Early settlers arrived with land grants issued for service in the War of 1812. In 1834, the Dover to Clarksville Road was used for Indian Removal.

Clarksville was established in November 1836 after Johnson County was formed from part of Pope County. The three commissioners involved—Abraham Laster, Elijah B. Alston, and Lorenzo N. Clark—did not agree immediately on a site. Eventually, the town was established on land donated by Josiah Cravens and named after Clark in an effort to get his support. The first court session was held in 1837 in a private building. Clarksville was incorporated on December 21, 1848.

Settlements around Clarksville’s center had been created by immigrants from Virginia, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Steamboat traffic as early as 1835 was provided by the Tom Bowlin and the William Parsons, while early stagecoach service was provided by the Little Rock–Springfield line of the Hunter, Hanger and Howell Stage Line. By July 1853, county commissioners authorized the investment of $16,000 in stock of the Little Rock and Fort Smith line of the Cairo and Fulton Railroad, but the area had no rail service until after the Civil War.

One of the first significant businesses was John Hill’s grocery store, which operated from the 1850s until the 1880s. A Federal Land Office was located in Clarksville in the 1830s and was active until 1859.

Early settlers started tobacco production, but most efforts later turned to cotton. By 1840, coal had been discovered in the Spadra area. Coal mining did not grow to be a viable industry until after the Civil War.

Augustus M. Ward established a school for the blind in 1849. A school for the deaf was founded in 1851 at the current site of the University of the Ozarks.

Early churches were of the Cumberland Presbyterian and Methodist faiths. The earliest known church was Cephas Washburn’s. Reverend Anderson Cox had established a congregation of Cumberland Presbyterians by 1840. The Methodists met in camp meetings for some years before establishing a formal church in 1841.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Captain John F. Hill organized a volunteer company that was mustered into service near Rogers (Benton County) as part of Colonel Dandridge McRae’s Sixteenth Regiment. Thomas King and Lymas Armstrong also organized groups of volunteers. Many local men also served in the Union army, most in the Second Regiment Arkansas Infantry.

Because of the town’s proximity to the river, troops of both armies passed through frequently. Colonel Thomas J. Churchill’s Confederate troops camped south of Clarksville during the winter of 1861, where many soldiers died of illness and were buried in unmarked graves in Oakland Cemetery. The Cumberland Presbyterian church was used as a hospital and then burned by departing Union troops, who also burned the Methodist church and the jail, and damaged the court house. Other military events that occurred in the area during the Civil War include an April 1864 affair and two skirmishes later that year.

An important step in the town’s recovery after the war was the 1871 survey work for the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad. Right-of-way acquisitions had started as early as 1867. After a change in ownership, the line was completed from Little Rock to Clarksville in 1873. By 1874, it had been completed to Fort Smith. The influx of Reconstruction officials, mine workers, and railway construction workers created a rowdy environment, which left Clarksville with an unsavory reputation. Better law enforcement later brought rapid improvement.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

Immigration after the Civil War was encouraged by a group of local citizens who advertised in newspapers in the Northeast. As coal mining began, many German and Austrian families came to the county both from their home countries and from Pennsylvania mining areas. Another source of immigrants was Union soldiers who had traveled through the state during service in the war.

Clarksville was home to several short-lived newspapers. By 1844, there was the Clarksville Sun, which continued under other names until at least 1850. The Herald and later Herald Democrat became the primary newspaper by the early 1900s. The Graphic, which merged with the Herald Democrat, still serves the town.

After Cane Hill College in Washington County closed in 1891, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church moved the school to Clarksville, and the school opened on September 8, 1891, as Arkansas Cumberland College. The school was renamed the College of the Ozarks in 1920 and became the University of the Ozarks in 1987.

Early Twentieth Century

The town initiated efforts to develop a flood control project in 1948 to control Spadra Creek, which flooded in 1914, 1927, and 1943. Once completed, this, together with the urban renewal projects of 1966–67, resulted in improved conditions.

The Citizens Band of Clarksville won a state music championship in 1915 and represented Arkansas at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. In 1902, the Daughters of the Confederacy erected the Clarksville Confederate Monument to honor those who died in the Civil War. In 1919, a group of veterans formed the Bunch-Walton post in honor of fallen soldiers from World War I.

The primary businesses of the area remained coal, gas, and agriculture through the Depression. In 1929, Clarksville’s gas field was the largest producing field in the state. Coal production was declining by 1933, but poultry later became, and remains today, a significant business.

The Clarksville National Guard Armory was built in 1930, and the Johnson County Municipal Airport was dedicated in 1934 with a visit from the aviation unit of the National Guard. It is today known as the Clarksville Municipal Airport. Also in 1934, a newer Johnson County Courthouse was begun; it was completed the following year. The Clarksville High School Home Economics Building was designed and constructed in 1936–37 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The College of the Ozarks housed a Civilian Pilot Training Program course beginning in 1942, as well as a naval training facility from 1944 to 1945. In December 1943, the navy began using the college for a course in the new radar technology. The first pharmacy school in the state was established at the college in 1946.

The 1950 Federal Census reported significant population growth in Clarksville, while other towns and Johnson County overall suffered declines. The establishment of the School of Pharmacy and general expansion at the College of the Ozarks added staff and students, while the rural population of the county began to move into town as jobs shifted to manufacturing and young men returned from military service.

A tornado substantially damaged the Clarksville area in February 1954. Significant gas exploration in the early 1950s in the area resulted in new producing wells by 1957. The poultry industry continued to grow as Priebe and Sons of Chicago built and opened a processing plant in 1952. The lumber and brick industries expanded, with the Eureka Brick & Tile Co. increasing to a production of 1.5 million bricks per month in 1955. A creosoting plant opened in 1954.

The College of the Ozarks was one of the first state private colleges to open to African-American applicants. In 1957, the college accepted five black applicants, all residents of Arkansas. The first of those to graduate was Lawrence Webb in 1959.

The public schools remained segregated until 1965 when, together with most counties in the state, Johnson County’s plan was accepted by federal courts. In the next year’s public school reports, the black Grace James School was no longer reported as operating.

Modern Era

Clarksville today represents a mix of agricultural and college town environments. Tyson’s poultry facilities are the largest single employer. The University of the Ozarks is now home to the Walton Fine Arts Center. The peach industry is celebrated by the annual Johnson County Peach Festival. Recreation facilities associated with the Ozark National Forest, local lakes, and the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation project offer new opportunities for growth of tourism. Clarksville is also one of nineteen locations where Depression-era post office art can be viewed. On January 24, 2018, Clarksville Light and Water, the local utility company, cut the ribbon on the state’s largest solar-powered municipal utility plant.

Education

Along with the schools for the blind and deaf, private schools were opened early in Clarksville’s development. Ewing Seminary was established in 1858 by the Cumberland Presbyterian Church and continued operation until it burned soon after the Civil War. The same group founded a female seminary in 1859. It was taken by Federal troops as a hospital, and it also burned a few years after the war. The College of the Ozarks also provided an academy for elementary and junior students until the consolidation of rural school districts in the pre–World War II period gave Clarksville a complete public school system.

Notable Figures

Clarksville has been home to Confederate soldier, attorney, and politician Arch McKennon; World War II flying ace Mac McKennon; and renowned educator and artist Imogene McConnell Ragon.

For additional information:

Clarksville–Johnson County Chamber of Commerce. http://www.clarksvillejocochamber.com/ (accessed September 8, 2022).

Langford, Ella Molloy. History of Johnson County, Arkansas: The First Hundred Years. Clarksville, AR: Johnson County Historical Society, 1981.

Mickel, Mrs. R. W. History of Johnson County, Arkansas. Clarksville, AR: 1985.

Jim McDaniel

Farmers Branch, Texas

Arkansas Cumberland College

Arkansas Cumberland College  Arlington Hotel

Arlington Hotel  Bunch-Walton Post 22 American Legion Hut

Bunch-Walton Post 22 American Legion Hut  Clarksville Armistice Day Parade

Clarksville Armistice Day Parade  Clarksville Confederate Monument

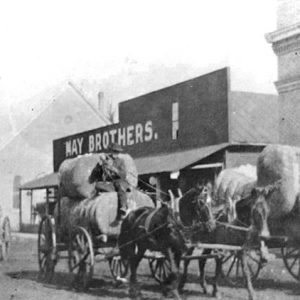

Clarksville Confederate Monument  Clarksville Cotton

Clarksville Cotton  Clarksville Depot

Clarksville Depot  Clarksville Gas Station

Clarksville Gas Station  Clarksville High School Building No. 1

Clarksville High School Building No. 1  Clarksville National Guard Armory

Clarksville National Guard Armory  Clarksville Post Office Art

Clarksville Post Office Art  Clarksville Presbyterian Church

Clarksville Presbyterian Church  Clarksville Skating Rink

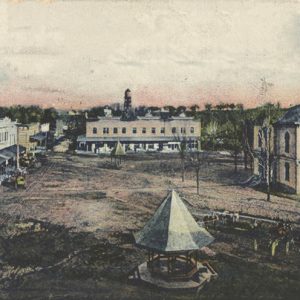

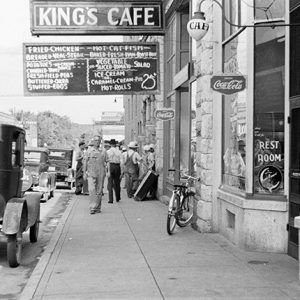

Clarksville Skating Rink  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Clarksville UCV

Clarksville UCV  Cumberland College

Cumberland College  Horsehead Lake

Horsehead Lake  Johnson County Courthouse

Johnson County Courthouse  Johnson County Map

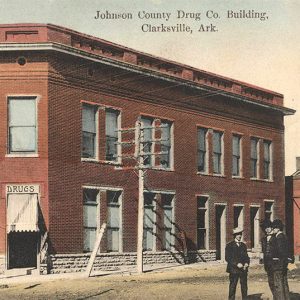

Johnson County Map  Johnson Drug

Johnson Drug  Arch McKennon Home

Arch McKennon Home  Old Stagecoach Inn

Old Stagecoach Inn  Peach Baskets

Peach Baskets  Riddell Theater

Riddell Theater  Veterans Day Parade

Veterans Day Parade

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.